A number of my middle-school students seemed to believe that recycling is the be-all and end-all of environmentalism.

We were trying to determine what type of material would make for the best drink bottles.

I have a deep reluctance to reflexively consider anything, “good for the environment,” considering that the environmental impact of any particular product is a complex thing to assess. My students, on the other hand, seem to think that recycling is good and all the rest of it can go hang.

I’d want to add up all the environmental costs: the raw materials; the energy input; the sources of the energy input; and the emissions to the air and water, especially all the other external costs of pollutants that people tend not to want to pay for. To my students, these things have been invisible.

Perhaps it’s the success of the environmental movement that’s pushed things to the background. We’re not struggling through smog everyday – although we’ve had some bad days this summer – and even big issues, like the BP oil spill, are a bit remote and seem so far away.

So, I tried showing the Story of Stuff today. It’s definitely a piece with a “point-of-view”, but I was hoping it would be provocative.

And it was.

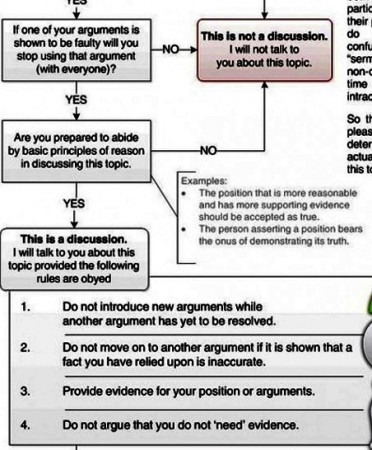

It certainly got a lot of the students agitated, ready to challenge its assertions about just how bad pollution problems really are today, which created a nice opening for me to point out the need for skepticism in the face of any information received. Of course, at that point they were probably a little skeptical about me too, but reasoned skepticism is at the heart of the scientific perspective I’d like them to learn as “apprentice” scientists.

I’d like them to read Orwell too, but that’s another battle.

One student was stimulated enough that, I hope, they’ll actually do a little research into the facts presented in the video and present their findings to the class.

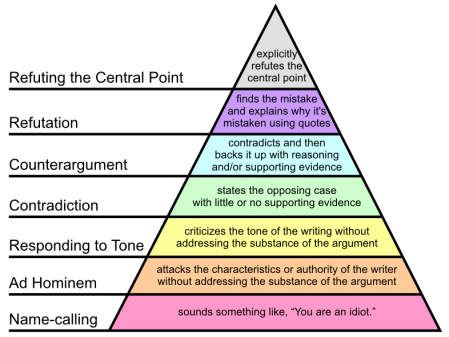

I’ll also have to do a little follow-up on how to argue. In particular I’ll need to post a picture of Paul Graham’s Hierarchy of Disagreement and point out that it’s better to try to refute the actual argument rather than attack the messenger.

We’ll see how it goes tomorrow.