My biology students are doing an exercise in genetics and heredity that requires them to combine the genes of two parents to see what their offspring might look like. They do the procedure twice — to create two kids — so they can see how the same parents can produce children who look similar but have distinct differences. To actually see what the kids look like, the students have to draw the faces of their “children”.

“I’m not going to claim that child as my own!”

I was walking through the class when I heard that. Apparently one student, who’d had a bit of art training, was paired with another student who had not.

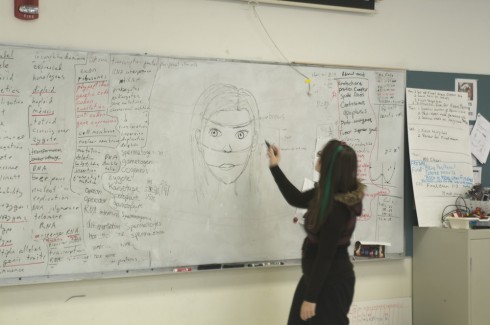

Fortunately, I was able to convince the more practiced artist to give the rest of the class a lesson on how to draw faces. She did an awesome job; first drawing a female face and then adapting it a bit to make it look more male.

If nothing else, I tried to make sure that the other students registered the idea that proportion is important in drawing biological specimens — like faces — from real life. Just getting the proportions right made a huge difference in the quality of their drawings. The forehead region should be the largest (from the top of the head to the eyebrows), then the area between the eyebrows and the bottom of the nose, then the nose to lips, and then, finally, the region from lips to chin should be shortest. You can see the proportion lines in the picture above.

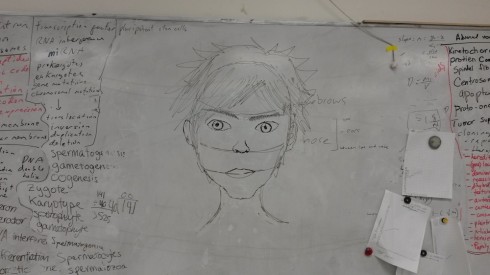

The adaptation stage, where she made the facial features more masculine, was also quite useful. The students had to think about what were typical male features and if there were a genetic basis to things like square chins.

Although all of the other students’ drawings improved markedly, including her simulated spouse’s, I don’t think my art-teaching student was absolutely happy with the end results after the one lesson. She ended up handing in two drawings of her own even though everyone else (including her partner) did one each.

However, having all the students on the same page, working with the same basic drawing methods, helped improve the heredity exercise because it reduced a lot of the variability in the pictures that resulted from different drawing styles and skill levels.

I also think that taking these interludes for art lessons are quite useful in a science class, since it emphasizes the importance of accurate observation, shapes student’s abilities to represent what they see in diagrams, and demonstrates that they can — and should — be applying the skills they learn in other classes to their sciences.