This year, I’ve been basing my introduction to basic chemistry for my middle school students around the periodic table of the elements. The first step, however, is to teach them how to draw basic models of atoms.

Prep: Memorization over the Winter Break

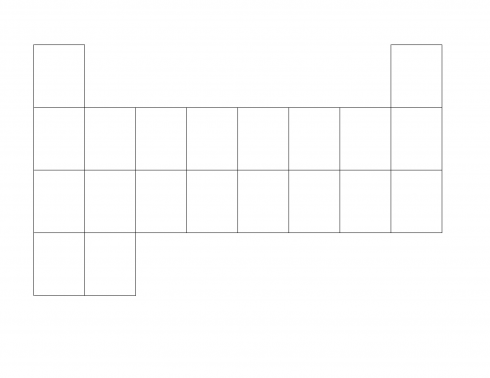

I started it off by having the students memorize the first 20 elements (H through Ca), in their correct order — by atomic number — over their winter break.

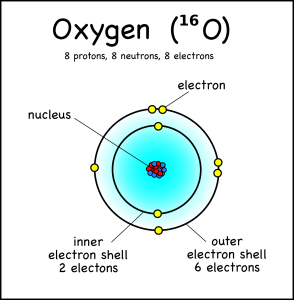

So that they’d have a bit of context, I went over the basic parts of an atom (protons, neutrons, and electrons) and made it clear that the name of the element is determined solely by the number of protons. I even had them draw a few atoms with the protons and neutrons in the center and the electrons in shells. Since I’d dumped all of this on them in a single class period, it probably was a bit much, but since it was just to give them some context I did not expect the 7th graders, who had not seen this before, to remember it all; for the 8th graders it should have been just a review.

Most students did a good job at the memorization. Some found songs on the the internet that helped, while others just pushed through. Having the two weeks of winter break to work on it probably helped too.

Day 1. Lesson: The Parts of an Atom

When we got back to school, the first thing I did was give them an outline of the upper part of the periodic table and asked them to fill it in with the element names.

After they’d filled out their periodic table template, I went into the parts of the atoms in more detail, and had them practice. The key points I wanted them to remember were:

-

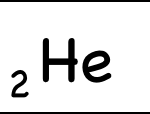

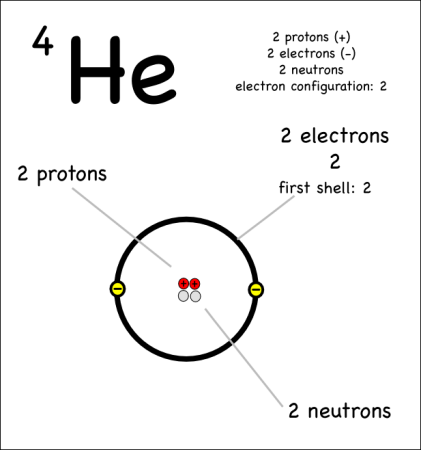

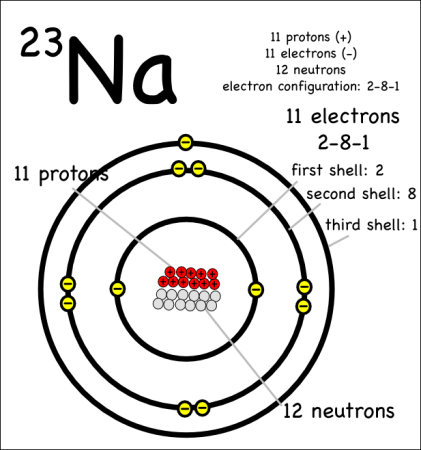

The atomic number is written as a subscript to the left of the element symbol. The atomic number is the number of protons. Since they memorized the elements in order, they should be able to figure this out on their own — but they could also look it up quickly on the periodic table, or look at the element symbol where the atomic number is sometimes written on the lower left.

- The atoms have the same number of electrons as protons. Protons are positively charged, and electrons are negatively charged, so an atom needs to have the same number of both for its charge to be balanced. We don’t talk about ions –where there are more or less electrons– until later.

-

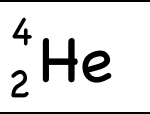

The atomic mass (4) is written as a superscript to the left of the element symbol. The atomic mass is the sum of the number of protons (2) and the number of neutrons (2). The small atoms that we’re looking at tend to have the same number of neutrons as protons, but that’s not necessarily the case. So how do you know how many neutrons? You have to ask, or look at the atomic mass number, which is usually written to the upper left of the atom. Since the atomic mass is the sum of the number of protons and neutrons, if you know the atomic mass and the number of protons, you can easily figure out the number of neutrons. (Note that electrons don’t contribute to the mass of the atom because their masses are so much smaller than the masses of neutrons and protons.

-

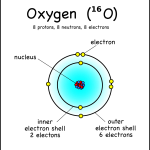

This oxygen atom has 8 electrons in two shells. Electron Shells: Electrons orbit around the nucleus in a series of shells. Each shell can hold a certain maximum number of electrons (2 for the first shell; 8 for the second shell; and 8 for the third). And to draw the atoms you fill up the inner shells first then move on to the outer shells.

So, if I wrote just the element symbol and its atomic mass on the board that students should be able to figure out the number of particles.

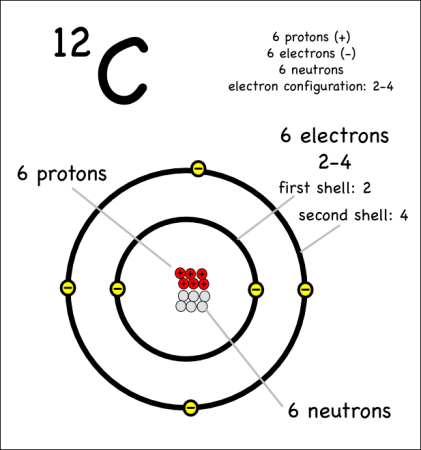

Example: Carbon-12

For example, the most common form (isotope) of carbon-12 is written as:

- Protons = 6: Since we know the atomic number is 6 (because we memorized it), the atom has 6 protons.

- Neutrons = 6 : Since the atomic mass is 12 (upper left of the element symbol), to find the number of neutrons we subtract the number of protons (12 – 6 = 6).

- Electrons = 6: This atom is balanced in charge so it needs six electrons with their negative charges to offset the six positive charges of the six protons. (Note: we haven’t talked about unbalanced, charged atoms yet, but the charge will show up as a superscript to the right of the symbol.)

- Electron shells (2-4): We have six electrons, so the first two go into filling up the first electron shell, and the rest can go into the second shell, which can hold up to 8 electrons. This gives an electron configuration of 2-4.

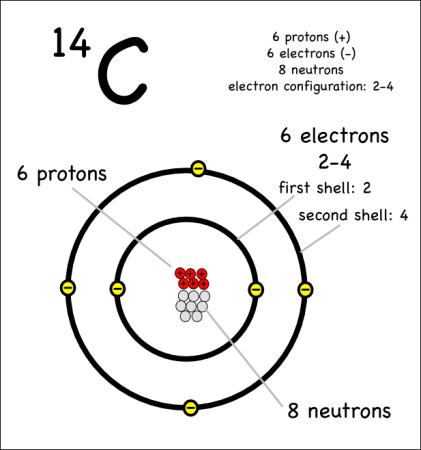

Example: Carbon-14

Carbon-14 is the radioactive isotope of carbon that is often used in carbon dating of historical artifacts. It is written as:

- Protons = 6: As long as it’s carbon it has six protons.

- Electrons = 6: This atom is also balanced in charge so it also needs six electrons.

- Neutrons = 8 : With an atomic mass of 14, when we subtract the six protons, the number of neutrons must be 8 (14 – 6 = 8).

The only difference between carbon-12 and carbon-14 is that the latter has two more neutrons. These are therefore two isotopes of carbon.

Example: Helium-4

Example: Sodium-23

Note: A picture of a hydrogen atom can be found here.

Update: I’ve created an interactive app that will draw atoms (of the first 20 elements), to go with a worksheet for student practice.