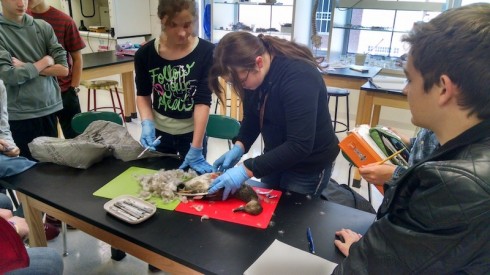

Dissection time is always interesting in the middle school classroom. Some kids start off a little squeamish, but there are always a few who pitch right in. All of the class were working on different organisms–microscopic algae (desmids), insects, plants, etc.–but I set up the dissection table in the middle of the room. With all the other tables facing inwards, everyone who wanted to got a chance to see the internal organs as they were carefully, but triumphantly, traced and extracted. It spreads the enthusiasm, and gives the other students a heads up as to what will be expected.

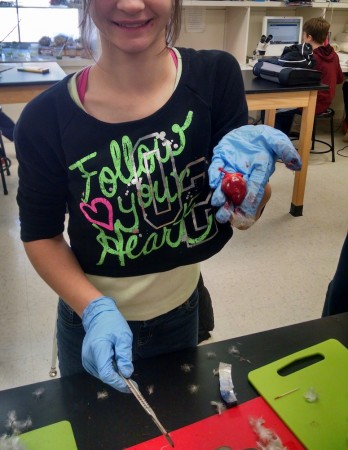

One student brought in a duck that her father had shot. She was familiar with cleaning hunted fowl, so had no qualms about the dissection. The duck was a great specimen, because the internal organs were large and easy to identify.

She, and most of the rest of the class, had dissected a sheep’s heart in elementary school. This time, however, they got to see how the heart was connected to the rest of the body. We got to talk about why smaller organisms, like ducks, could get away with two chambered hearts, while larger ones need four chambers.

Indeed, the tracing of the artery leading out of the heart lead us to compare of the color of the duck’s lungs–so red they were almost black–and the fish’s gills, which were also a deep red. And that, in turn lead to a discussion of how organisms ingest the gasses they need to survive: microbes through diffusion; insects through spiracles and trachea; mammals through lungs. Tomorrow we’ll talk about how the surface area to volume ratio changes with size.