Back in the day, if you wanted a non-stick cooking skillet, your best option was to do it yourself by seasoning a cast metal pan. Sheryl Canter has an excellent post describing the science behind the “seasoning” process. The key is to bake on a little bit of oil to create a strong cross-linked polymer surface. This is a nice tie into our discussion of polymers and polymerization in the middle school science class; although I’m not sure how many of my students have actually seen a cast iron pan, or even know what cast iron is.

To season, you coat the pan with a thin layer of oil and bake it for a while (without anything in it). Baking releases free radicals from the metal that react with the oil to create a cross-linked polymer that’s really hard to break down or wear out, and prevent food from sticking to the pan. Different, cross linked polymers are used in car tires for their durability, but probably not for their lack of stickiness.

Apparently, linseed oil is the best seasoning agent, but it might be a bit hard to find.

Most non-stick, artificial surfaces, are also made of polymers of hydrocarbons, silicon oxides and other interesting chemicals.

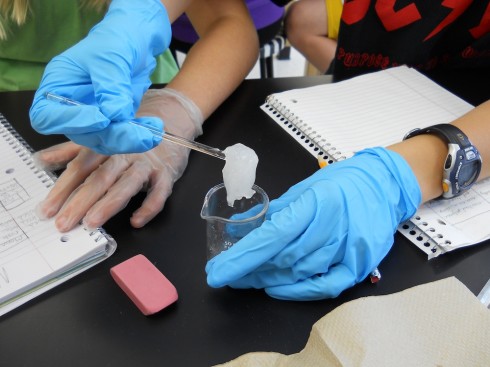

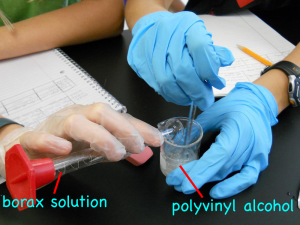

In the lab, you can make your own cross-linked polymer “slime” by adding a solution of borax (sodium tetraborate) to a solution of polyvinyl alcohol (1:1 ratio of concentrations) (Practical Chemistry, 2008).

The result is a satisfying goo.