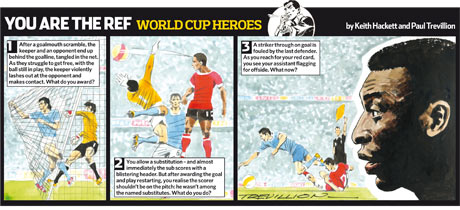

Every week, artist Paul Trevillon poses, in text and cartoon form, some truly idiosyncratic situations that might come up in a soccer match in his You are the Ref strip on the Guardian website. Readers get a week to propose their solutions and then referee Keith Hackett give his official answers.

It’s a fascinating series, the subtext of which is that, while there is a lot of minutiae to remember – the actual diameter of a soccer ball is important for one question – the game official is really out there to enforce the spirit of the laws, enabling fair and fluid play to the best of their ability. This is a useful lesson for adolescents who tend toward being extremely literal, and have to work on their abstract thinking skills, especially when they relate to questions of justice. For this reason, I find that when refereeing their games it’s useful to take the time during the game, and afterward in our post-match discussions, to talk about the more controversial calls.