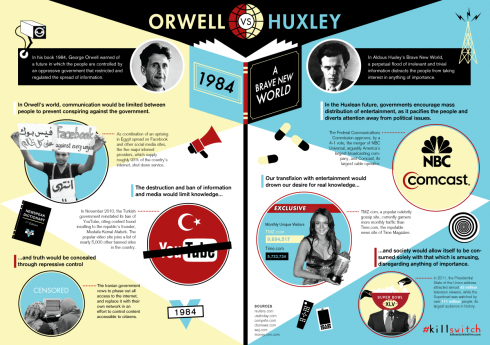

World-shaker tries to draw the modern parallels to 1984 and Brave New World in graphic form.

Orwell’s (1948) distopian view of the future in 1984, warned against the government developing the ability to exert constant, repressive monitoring of everyone, controlling the means of communication and, perhaps more importantly, the use of language. Huxley’s (1932) Brave New World, on the other hand, saw a mass media using your apparent predilection for trivialities to distract you from the important things. These two books are staples of secondary school literature, and it’s easy to see modern parallels; “kinetic military action” is currently my favorite Orwellian term.

Unfortunately, drawing modern parallels to historic literature is fraught with difficulty because it’s so easy: the human brain is predisposed to seeing patterns. World-shaker’s attempt is interesting, but flawed. One of his commenter points out that he compares the entertainment website TMZ to Time.com’s news site, which only gets half as many visitors. However, the New York Times’ site gets three times as many visits as TMZ so perhaps he’s fudging the statistics a little to show the trend toward frivolous media.

There are other examples, but the graphic makes does provide a basis for an interesting conversation. The most interesting aspect is that it shows the U.S.A trending more toward Huxley, while repressive Middle-Eastern regimes seem to be trying to make Orwell’s vision more of a reality.