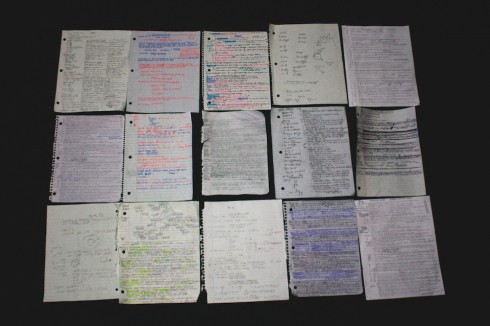

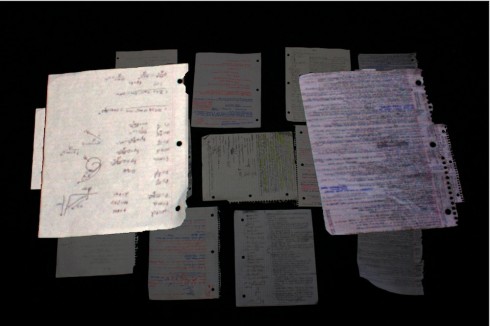

I let my students bring in one page of handwritten notes, a “cheat sheet” if you will, into their last Physics exam. I’d expected to see some very tiny writing, but some of the notes needed scientific-grade magnification equipment to be read. Seen from a distance, the dense writing did have a certain aesthetic appeal.

Of course the primary reason for letting students bring in the cheat sheets into the exam was to get them to practice taking notes. At one extreme, the students who already take good notes benefit from having to condense them. At the other extreme, the students who don’t take notes at all get a strong incentive to practice. The very act of preparing cheat sheets is a good way to study for exams.

And it worked. As they hand in their papers I usually ask them how the test went, and, this time, I also asked a few student if they found their page of notes useful. One student in particular responded, Well I didn’t need to use it after making it.

It was also very interesting to see the different styles of note taking: the strategic use of color; densely packed text; equations; diagrams; columnar organization. What all this means, I’m not sure. I’m particularly interested in how their note taking style relates to students’ preferred learning style.

Indeed, it would be interesting to see if the note taking style co-relates in any way with students’ performance on the test. One could hypothesize that, since we know that students learn better when they encounter material from multiple perspectives, then students whose notes have the greatest mix of styles — diagrams, equations, text etc. — should have learned more (and perhaps perform better on the test).

It’s a pretty simple and crude hypothesis, since there are likely many other factors that affect test performance, but it would still be interesting to look at.