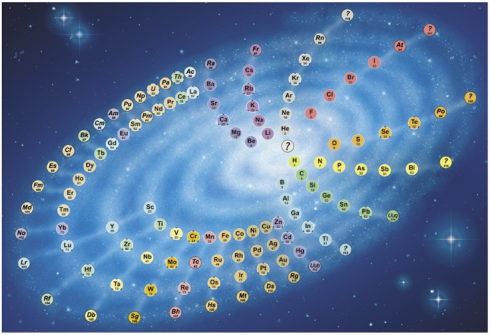

The objective is to show the shape of the whole and to express the beauty and cosmic reach of the periodic system.

— Stewart (2006): The Chemical Galaxy

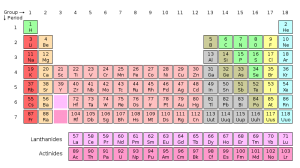

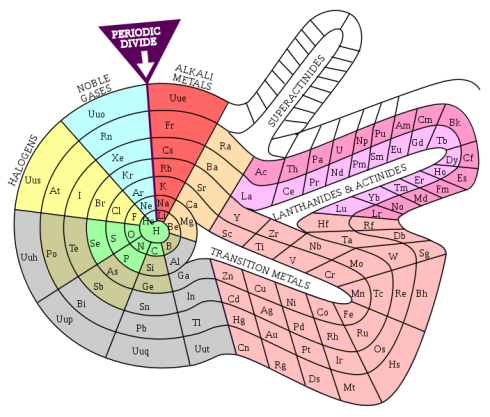

The traditional periodic table of the elements breaks the elements into rows as their chemical and physical characteristics repeat themselves. But since the sequence of elements is really a continuous series that gradually increases in mass, a better way of displaying them might be as the spiral, sort of like the galaxy.

When the chemical elements are arranged in order of their atomic number, they form a continuous sequence, in which certain chemical characteristics come back periodically in a regular way. This is usually shown by chopping the sequence up into sections and arranging them as a rectangular table. The alternative is to wind the sequence round in a spiral. Because the periodic repeats come at longer and longer intervals, increasing numbers of elements have to be fitted on to its coils. …

The resulting pattern resembles a galaxy, and the likeness is the basis of my design. It seems appropriate, as the chemical elements are what galaxies are made of.

…

The ‘spokes’ of the ‘galaxy’ link together elements with similar chemical characteristics. They are curved in order to keep the inner elements reasonably close together while making room for the extra elements in the outer turns.

— Stewart (2006): The Chemical Galaxy

While the spiral version of the periodic table is not used a lot, it is scientifically valid. There are other ways of representing the spiral and the periodic table itself. It all depends on what you want to show.

Indeed, Mendeleev’s monument in Bratislava, Slovakia has the elements arranged as the spokes in a wheel.

The first ever image of the periodic system was a helix, wound round a cylinder by a Frenchman, Chancourtois, in 1862. Mendeleev himself, who published his famous table in 1869, wrote “The series of elements is uninterrupted and corresponds, to a certain degree, to a spiral function.” The first spiral with a circular outline was by Baumhauer in 1870, and the first to give it an oval outline was Clark in 1933. The oval was smoothed into an ellipse by Longman in 1951, and his giant coloured mural was my inspiration for my “Galaxy”. The human eye evolved in a world of curved forms; straight lines and right angles only became common with the invention of bricks. A spiral appeals to our visual system in a way that a table cannot do. I think chemistry should offer beauty as well as truth.

Philip Stewart: I think chemistry should offer beauty as well as truth.

I’m going to have to remember that phrase. Scientific truth has its own intrinsic beauty, I feel, but expressing it tangibly is a challenge. It’s good to have your artwork (and your prose).

This is so beautiful. And I like that quote too! All science is beauty – if we can just see it 🙂