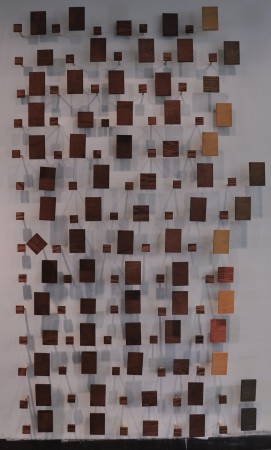

The one rotated piece represents the volta of the sonnet, the moment at which the poem pivots from exploring a dilemma to developing a resolution. Volta translates from Italian to turn in English so the physical translation of that structural device is quite literally done.

— Bert Geyer (2011).

Last year, my middle school class spent a fair amount of time looking at sonnets: pulling them apart; comparing similarities and differences; discovering their poetic form; and then each creating their own.

Bert Geyer took this type of analysis to the next step. He created a visual translation of a Petrarchan sonet using color and shape to represent the patterns of the sonnet.

The artist’s description of the piece is quite fascinating.

The varying stains at the ends of the lines indicate rhyme scheme. I chose to use the Petrarchan format–abbaabbacdcdee. Overall, every feature of the piece takes precedent from the composite structure of a sonnet (not any specific sonnet). But the piece isn’t an exact analog. My aim through this piece is to observe the nuances and complexities of translating from one medium to another. How certain features may be reproduced in another medium, albeit differently. And how translation to a new medium has limitations and new opportunities.

— Bert Geyer (2011).

I particularly appreciate that the statement so clearly demonstrates the care and effort that went into the details of the piece. The illustration that the creation of art requires just as much thought and energy as in any other field.

This should make an excellent, spark-the-imagination, addition to any discussion of sonnets. Indeed, it can also serve as a template for how to analyze different types of poetry to look for their forms. And the meaning of all the different parts should just jump out to Montessori (and any other) students who’ve used geometric symbols to diagram sentences.