“On average we found that each of us carries two or three mutations that could cause one of these severe childhood diseases.”

–Stephen Kingsmore, physician, Children’s Mercy Hospital in Greenfieldboyce (2010), New Genetic Test Screens Would-Be Parents.

NPR’s All Things Considered had two related articles on last night that deal with the specific topics we’re covering this week: genetic disease and recessive alleles.

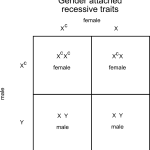

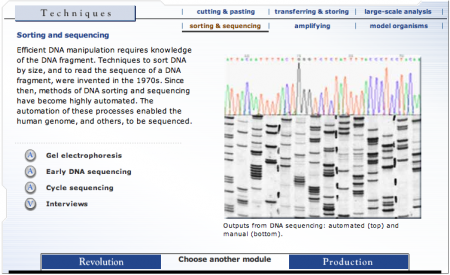

The first one is about the latest in genetic screening technology, for determining if potential parents have recessive alleles that could combine to produce children with genetic diseases. Recent research has made this much easier.

The second touches on the ethical consequences of genetic screening. It could lead to an increase in abortion rates and leads us along the slippery slope of eugenics.

This second story would make an interesting basis for a Socratic dialogue. As would, I think, the movie Gattica, which deals with the consequences of genetic screening and genetic customizations. I see it’s PG-13 so we may be able to screen it. Similarly, I may recommend Brian Stableford’s War Games to my eight graders who might like a military science fiction book that deals with genetic optimization. Alternatively, Nancy Kress’ Beggars in Spain might offer another interesting perspective on this issue.