Abstract

The power of capitalism lies in the system’s ability to adapt to the needs of people. It does so by giving preferential rewards to those who best meet those needs as expressed in the market. As part his spring Independent Research Project, middle school student, Mr. Ben T., came up with a simulation game that demonstrates this advantage of capitalist systems over a communal systems that pays the same wage irrespective of the output.

Background

In either the fall or the spring term I require students to include some type of original work in their Independent Research Project (IRP). Most often students take this to mean a natural science experiment, but really it’s open to any subject. Last term one of my students, Ben T., came up with a great simulation game to compare capitalism and socialism. With his and his parent’s consent I’m writing it up here because I hope to be able to use it later this year when we study economic systems and other teachers might find it interesting and useful.

Procedure

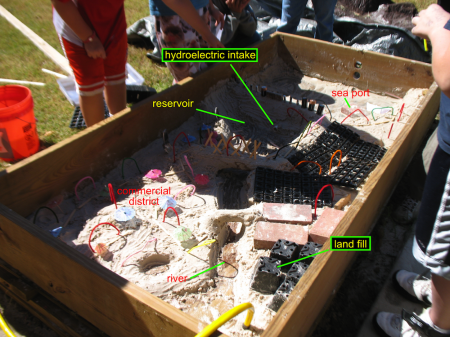

The simulation was conducted with six students (all 7th graders because the 8th graders were in Spanish class at the time) who represented the producers in the system, and one student, Ben, who represented the consumers.

Simulating Capitalism

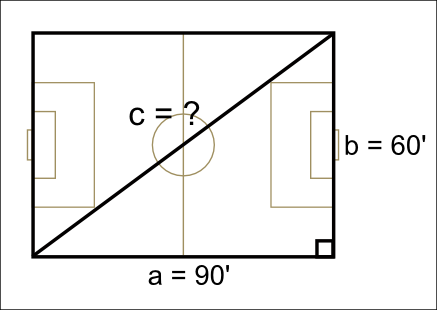

In the first stage, representing capitalism, the producers were told that the consumer would like a car or cars (at least a drawing to represent the cars) and the consumer would pay them based on the drawing. The producers were free to work independently or in self-selected teams, but only one pair of students chose to team up.

Producers were given three minutes to draw their cars, which they then brought to “market” and the consumer “bought” their drawings. The consumer had limited funds, 10 “dollars”, and had to decide how much to pay for each drawing. Producers were free to either accept the offered payment and give the drawing to the consumer or keep their drawing.

This procedure was repeated three times, each turn allowed the producers to refine their drawings from the previous round, particularly if it had not sold, or create new drawings. Since all drawings were offered in an open market, everyone could see which drawings sold best and adapt their drawings to the new information.

Simulating Socialism

Socialism was simulated by offering equal pay to all the producers no matter what car/drawing they produced. Otherwise the procedure was the same as for the capitalism simulation: students were told that they could work together or in teams; they brought their production to market; the consumer could take what they liked or reject the product, but everyone was still paid the same.

Assessment

At the end of the simulations consumer students were asked:

- How did you change your car in response to the market?

- Did it make the car better?

- What do you think of a socialist system?

- Which [system] do you prefer?

Results

Students showed markedly different behaviors in each simulation, behaviors that were almost stereotypes capitalist and communistic systems.

Capitalism simulation

Producers in the capitalist simulation started with fairly simple cars in the initial round. One production team drew a single car. Another made four cars with flames on the sides, while another went with horns (as in bulls’ horns rather than instruments that made noise) and yet another drew. When brought to market, despite the fact that almost all drawing were paid for, it quickly became obvious that the consumer had a preference for the more “interesting” drawings. The producer who drew six cars with baskets on top got paid the most.

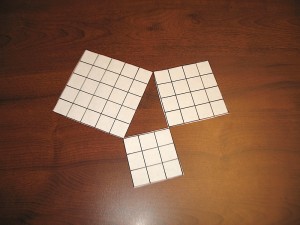

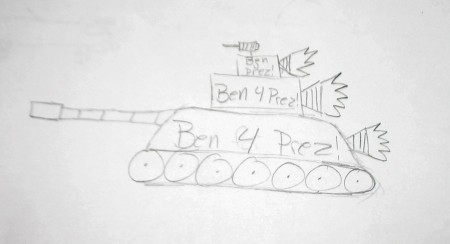

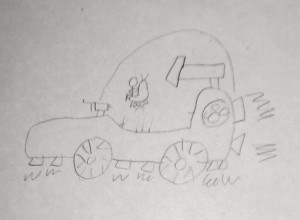

In the second round one innovator came up with the idea of adding a rocket launcher (Figure 2) and was amply rewarded. In response, in the third round, the market responded to this information with enthusiasm, however, all the rocket launchers were trumped by a tank shooting fire out its back with, “Ben 4 Prez!” written on the side (Figure 1).

The producers responded the the preferences of the consumer. The best example of this was the work of the couple students who decided to pair-up.

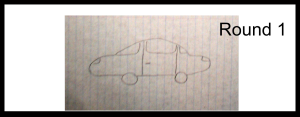

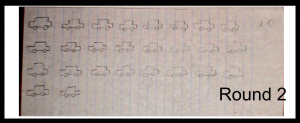

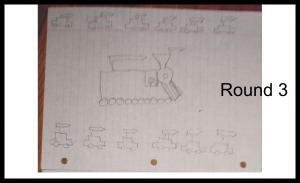

Their first car was simple and straightforward and it only garnered one “dollar” (Figure 3a). In the second round they chose to go with quantity, producing a lot of cars (Figure 3b) as that had been a fairly successful strategy of another producer in Round 1. Their reasoning was that since there were two of them they would be able to outproduce the others. By the final round they had developed a train with rocket launchers in addition to a set of cars with rocket launchers (Figure 3c). Again, market pressures had an enormous influence on the final vehicles, but the individual philosophy of the producers also showed through in the vehicle production choices.

[UPDATE 5/17/2012]: The capitalism part of the simulation produces winners and losers, and a good follow-up is to do the distribution of wealth exercise to see just how much wealth is concentrated at the top in the U.S.. The second time I ran the simulation — with a different class — the students were quite put out by the economic disparity that resulted and ended up trying to stage a socialist revolution (which precipitated a counter-revolution from the jailed oligarchs).

Socialism Simulation

Although three rounds were intended, time constraints limited the socialism simulation to a single round, however the results of that single round were sufficient for students to identify the main challenges with communal rewards for production. The producers decided that they would work together and produced two sets of basic cars (Figure 4). Half of the students did not even contribute, they spent their time just standing around. It was the stereotypical road construction crew scene.

Survey Responses

All students who responded to the question preferred capitalism, the primary reason being injustice “… cause [during the socialism simulation] some people do nothin’ [and] other people do something.”

Discussion and Conclusion

Using only one consumer reduces the time needed for the simulation but limits students from seeing that markets can be segmented and different producers can fill different niches. It would be very interesting to see the outcome of the same simulation in a larger class.

The small class size also allowed the simulation to take place in less than half an hour. Most of the post processing of the information gained was done by the student who ran the simulation since it was part of his Individual Research Project. While he did a great job presenting his results at the end of the term, when I use this simulation as part of the lesson on economic systems I would like to try doing a group discussion at the end.

I’m also curious to find out how much more the cars would evolve if given a few more rounds. Which brings up an interesting point for consideration. Since some students have already done the simulation, it may very well influence their actions when I do it again this year. It would probably be useful to make sure that there are more than one consumers, or that there consumer has very different preferences compared to Ben T.. A mixed gender pair of students might make the best set of consumers.