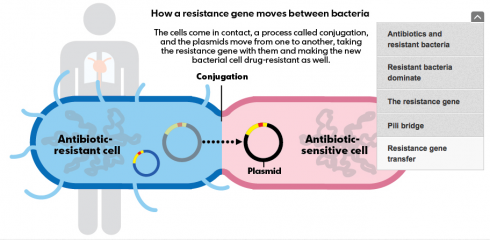

Peter Eisler has a somewhat scary article on the development of drug resistance in bacteria at the University of Virginia Medical Center. The bacteria were resistant to all of their antibiotics. Everything. And the bacteria were able to pass the genes that gave them their resistance to other bacteria: not just to their offspring, but horizontally to other species of bacteria by exchanging bits of DNA called plasmids.

When genes are passed on from parent to offspring, or even from one microbe to another by cell splitting, it’s called vertical gene transfer. Horizontal transfer, on the other hand, involves different individual organisms passing genes from one to the other. It would be as if two people could exchange genes by shaking hands.

When the doctors began analyzing the bacteria in their first patient, who’d transferred from a hospital in Pennsylvania, they found not one, but two different strains of CRE bacteria. And as more patients turned up sick, lab tests showed that some carried yet another.

“We were really frustrated; we hadn’t seen anything like this in the literature,” says Costi Sifri, the hospital epidemiologist. “The fact that we had different bacteria told us these cases were not related, but the shoe leather epidemiology suggested to us that all these (infections) came from the same patient. … We realized we might be seeing a mobile genetic event.”

In other words, it looked like a single resistance gene was jumping among different bacteria from the Enterobacteriaceae family, creating new bugs before their eyes.

— Eisler 2012: Deadly ‘superbugs’ invade U.S. health care facilities in USA Today.

The really scary part:

There is little chance that an effective drug to kill [drug resistant] CRE bacteria will be produced in the coming years. Manufacturers have no new antibiotics in development that show promise, according to federal officials and industry experts, and there’s little financial incentive because the bacteria adapt quickly to resist new drugs.