The Guardian has an excellent video that explains how the images from the Hubble Space Telescope are created.

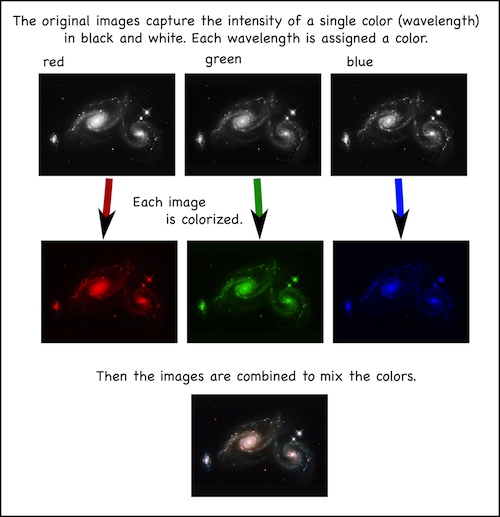

Each image from most research telescopes only capture certain, specific colors (wavelengths of light). One camera might only capture red light, another blue, and another green. These are captured in black and white, with black indicating no light and white the full intensity of light at that wavelength. Since red, blue and green are the primary colors, they can be mixed to compose the spectacular images of stars, galaxies, and the universe that NASA puts out every day.

The process looks something like this:

NASA’s image of the day is always worth a look.