Abstract

The power of capitalism lies in the system’s ability to adapt to the needs of people. It does so by giving preferential rewards to those who best meet those needs as expressed in the market. As part his spring Independent Research Project, middle school student, Mr. Ben T., came up with a simulation game that demonstrates this advantage of capitalist systems over a communal systems that pays the same wage irrespective of the output.

Background

In either the fall or the spring term I require students to include some type of original work in their Independent Research Project (IRP). Most often students take this to mean a natural science experiment, but really it’s open to any subject. Last term one of my students, Ben T., came up with a great simulation game to compare capitalism and socialism. With his and his parent’s consent I’m writing it up here because I hope to be able to use it later this year when we study economic systems and other teachers might find it interesting and useful.

Procedure

The simulation was conducted with six students (all 7th graders because the 8th graders were in Spanish class at the time) who represented the producers in the system, and one student, Ben, who represented the consumers.

Simulating Capitalism

In the first stage, representing capitalism, the producers were told that the consumer would like a car or cars (at least a drawing to represent the cars) and the consumer would pay them based on the drawing. The producers were free to work independently or in self-selected teams, but only one pair of students chose to team up.

Producers were given three minutes to draw their cars, which they then brought to “market” and the consumer “bought” their drawings. The consumer had limited funds, 10 “dollars”, and had to decide how much to pay for each drawing. Producers were free to either accept the offered payment and give the drawing to the consumer or keep their drawing.

This procedure was repeated three times, each turn allowed the producers to refine their drawings from the previous round, particularly if it had not sold, or create new drawings. Since all drawings were offered in an open market, everyone could see which drawings sold best and adapt their drawings to the new information.

Simulating Socialism

Socialism was simulated by offering equal pay to all the producers no matter what car/drawing they produced. Otherwise the procedure was the same as for the capitalism simulation: students were told that they could work together or in teams; they brought their production to market; the consumer could take what they liked or reject the product, but everyone was still paid the same.

Assessment

At the end of the simulations consumer students were asked:

- How did you change your car in response to the market?

- Did it make the car better?

- What do you think of a socialist system?

- Which [system] do you prefer?

Results

Students showed markedly different behaviors in each simulation, behaviors that were almost stereotypes capitalist and communistic systems.

Capitalism simulation

Producers in the capitalist simulation started with fairly simple cars in the initial round. One production team drew a single car. Another made four cars with flames on the sides, while another went with horns (as in bulls’ horns rather than instruments that made noise) and yet another drew. When brought to market, despite the fact that almost all drawing were paid for, it quickly became obvious that the consumer had a preference for the more “interesting” drawings. The producer who drew six cars with baskets on top got paid the most.

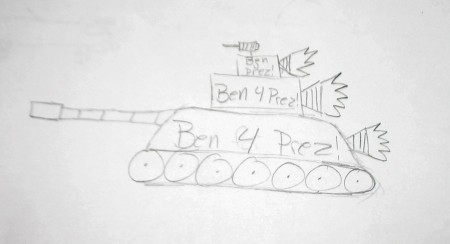

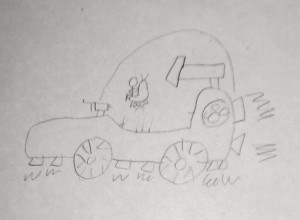

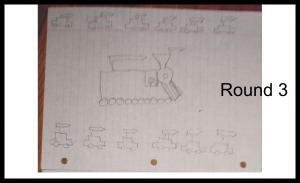

In the second round one innovator came up with the idea of adding a rocket launcher (Figure 2) and was amply rewarded. In response, in the third round, the market responded to this information with enthusiasm, however, all the rocket launchers were trumped by a tank shooting fire out its back with, “Ben 4 Prez!” written on the side (Figure 1).

The producers responded the the preferences of the consumer. The best example of this was the work of the couple students who decided to pair-up.

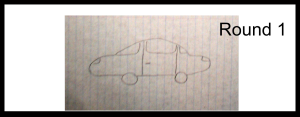

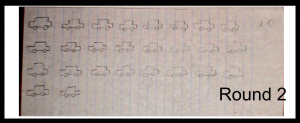

Their first car was simple and straightforward and it only garnered one “dollar” (Figure 3a). In the second round they chose to go with quantity, producing a lot of cars (Figure 3b) as that had been a fairly successful strategy of another producer in Round 1. Their reasoning was that since there were two of them they would be able to outproduce the others. By the final round they had developed a train with rocket launchers in addition to a set of cars with rocket launchers (Figure 3c). Again, market pressures had an enormous influence on the final vehicles, but the individual philosophy of the producers also showed through in the vehicle production choices.

[UPDATE 5/17/2012]: The capitalism part of the simulation produces winners and losers, and a good follow-up is to do the distribution of wealth exercise to see just how much wealth is concentrated at the top in the U.S.. The second time I ran the simulation — with a different class — the students were quite put out by the economic disparity that resulted and ended up trying to stage a socialist revolution (which precipitated a counter-revolution from the jailed oligarchs).

Socialism Simulation

Although three rounds were intended, time constraints limited the socialism simulation to a single round, however the results of that single round were sufficient for students to identify the main challenges with communal rewards for production. The producers decided that they would work together and produced two sets of basic cars (Figure 4). Half of the students did not even contribute, they spent their time just standing around. It was the stereotypical road construction crew scene.

Survey Responses

All students who responded to the question preferred capitalism, the primary reason being injustice “… cause [during the socialism simulation] some people do nothin’ [and] other people do something.”

Discussion and Conclusion

Using only one consumer reduces the time needed for the simulation but limits students from seeing that markets can be segmented and different producers can fill different niches. It would be very interesting to see the outcome of the same simulation in a larger class.

The small class size also allowed the simulation to take place in less than half an hour. Most of the post processing of the information gained was done by the student who ran the simulation since it was part of his Individual Research Project. While he did a great job presenting his results at the end of the term, when I use this simulation as part of the lesson on economic systems I would like to try doing a group discussion at the end.

I’m also curious to find out how much more the cars would evolve if given a few more rounds. Which brings up an interesting point for consideration. Since some students have already done the simulation, it may very well influence their actions when I do it again this year. It would probably be useful to make sure that there are more than one consumers, or that there consumer has very different preferences compared to Ben T.. A mixed gender pair of students might make the best set of consumers.

What exactly is supposed to be the capital in this simulation?

Great question. Maybe I’ve been too careless with my terms. The capital is inferred (it’s the means for producing the “cars”): in the “capitalist” economy it’s theoretically owned by the individuals, who can, via free association pool their resources.

Perhaps a better description of the simulation would be market versus command economy?

Unfortunately you didn’t finish the experiment with socialism, allowing it to run for the same number of iterations.

An interesting question would be, after the same number of iterations, did the products from the capitalist compare in market fitness to the socialistic ones?

The fact that a share of people did not contribute to the socialistic experiment is not, in my view, a problem: we all know the problem with capitalism is the induced scarcity and overproduction, meaning only the contribution from a minority of actors is needed. So it is perfectly possible the quality of the product from a “voluntary” (driven by the will to do a good job) team could be better or as good as a the products from a “driven” (driven from the need for profit, and fear of failure) team.

Other considerations apply, but are far more difficult to consider in your experiment: total cost for society (labor and resources) as a whole of the two experiments, the quality (car: how much will it consume, how much time will it last before breaking, how secure is, how reciclable, …) of the goods produced in the two systems.

Nice experiment and thank you for publishing.

I’m glad you (ilgatto) found the exercise useful. I really appreciate the feedback.

I was thinking about this quality issue last night as I was writing something on free enterprise. The object that came to mind (for better or worse) was the AK47, which has been awfully effective and popular, but came out of communist USSR. Kalashnikov designed it under the pressure of WWII, out of patriotism, and never got any royalties for it as far as I know.

The other example is Wikipedia. If the idea behind it is not socialist, I’m not sure what is.

My hope with this exercise is that the game conveys the basic, fundamental ideas about the difference between free markets and command&control economies. The other stuff can come later. I try to temper the unrestrained, free-market cheerleading that this exercise can lead to, with the distribution of wealth exercise, which most students find chastening.

I have been thinking a little about how to adapt the game to consider the bigger-picture externalities you mention. They tie in to Dave Engle’s comment at the top about where’s the capital. I have not yet found a good way to include these other concepts within the game without making it over-long, but I’m sure it can be done.

There is an enormous amount of material here presented as common sense that just stinks of a biased study. Why did the producers choose just two “basic” cars for the socialists? Couldn’t they have asked the single consumer (another huge problem) to accept or reject a plan, and allowed for a chance to go back to the drawing board? You mention that half of the socialism class didn’t participate and virtually no one in the capitalism class teamed up, but couldn’t 10 kids who were excited to participate produce a better car than any one kid excited to participate?

Finally, there is no mention here that whatever car the socialists turned out would have come at half of the cost of the capitalist car, because there wouldn’t be obscene corporate profits (although there could be some), and that all of the workers would have been unioned and had a say in the direction of the company, which would be more fulfilling work, and none of them would ever have there jobs shipped overseas.

I think its a great idea to give kids exposure to both capitalism and socialism, but if its not going to be informed and objective than all you have is yet another pseudo–study demonizing socialism. And that’s hardly original.

Great points about the problems with this exercise. In particular, I appreciate your (fraud laser) suggestions for improving the socialism part of the game; I agree it does not give socialists a fair shake. I’ll respond to your points specifically below, but I think it’s important to point out that my Montessori students go to school in an environment that is designed much more like a socialist community than a free-market competition.

I think the next time I try this exercise I’ll have them do socialism first, and allow them a couple turns to allow this type of feedback. This should also help accommodate the possibility that after going through the capitalism phase the student may have been getting a bit tired so they would put less effort into their socialist cars.

I can’t disagree here. I actually tried another variant of the game about a month or so ago where I did allow multiple consumers. The results were not nearly as tidy (especially since some students involved had already done the version described above): the marketplace for selling cars was raucous, very much like the stock market trading floor, which was nice, but the students showed the same level of disinterest at the idea of working together to put together a socialist car.

I think they could, but only if you gave them the entire day (or probably the week) to get it done. Having 10 students design a car by committee would be a ridiculously inefficient process. These same students do these problem-solving meetings all the time, addressing everything from organizing rules of behavior for the classroom, to deciding on what food to buy to take on our immersions. It is unbelievable how much time it took for the group to decide that each person leaving or entering the room should be responsible for closing the door behind them. If I remember my Montessori training correctly, as a general rule of thumb, it takes adolescents three times a long to do this type of thing than it would take an equivalent number of adults, and I would say this applies to students who are experienced with running and participating in committee meetings (which my students are by this time of the year).

Capitalism is messy, unfair and unsafe, but for those very reasons it generates a lot of innovation. One of the points that I like about the game as described is that the market economy phase very quickly identified the likes and dislikes of the (sole) consumer. In fact, I believe (speculation admittedly) that even the consumer didn’t really know his own preferences when the game started, but he and the producers very quickly found it out because everyone could see what was going on in the transparent marketplace.

In my recent variation of the game, the one with multiple consumers and producers, an economic disparity quickly developed between students who were successful in the market and those who were not. I exacerbated the situation to make it a social disparity as well, by making the “wealthiest” students sit on the higher level of the risers and the “poorest” students sit on the floor. This made the problems of income and wealth disparities more prominent.

Then I had the “poor” students stage a socialist revolution, and they became the central planning committee. And they did a good job being fair to everyone, but the radical change in circumstance lead to resistance from the former “oligarchs”.

For all my little forays into markets, the Montessori Middle School classroom is run very much like a miniature socialist community, and the student-run-business (SRB) has quite the democratic organization. In particular, although the SRB has a hierarchical management system, it’s the students who decide who gets what job, and they came up with the system that allows them to rotate through all the responsibilities fairly so everyone gets a chance to see the system from the perspective of both worker and management. They also have to deal with the problems that crop up as a group, including issues that plague socialist communities like social loafing. They make the choices about the direction of the company (should we add bread-baking? should we try a plant sale this year?). At one point this year they actually had a discussion about having an SRB “union” but decided to reinforce the mechanisms to protect workers’ rights instead. They make these decisions knowing that the corporate profits from the business are the only source of funds for their end-of-year trip. Even the destination of the trip itself is put up and voted on by proposal; this is the first year (out of three) that my proposal won.

Any simulation requires some simplification, so you’re guaranteed to miss some nuance. I appreciate the ideas for improving the socialist aspect of the game; I’ll definitely try them in the future. What I like about this game is that it highlights the innovation inherent to free-markets, and at least points out the socioeconomic inequalities that result. It’s not done in a vacuum, however, the distribution of wealth exercise acts as a complement.

“They” say that all models are wrong, but some are useful. Despite the bias of this particular game toward capitalism, I still find this exercise to be useful. The Montessori classroom is specifically designed to encourage community, but it’s important for these students to recognize that free market competition has some advantages too.

Thanks again for the comments. I really appreciate the feedback.

What a caricature of Socialism. Indoctrinate them young, eh?

It would certainly like to hear any suggestions that might make the simulation more accurate. We try to indoctrinate students with the idea that comments (and criticisms) alone aren’t particularly useful. Despite all the problems with this simulation, I think it gets to the essential problem that advocates of socialism have to deal with: how to get everyone invested and participating. It also highlights the primary issue with capitalism — distribution of wealth. The second time I did the simulation my students dealt with this by trying to stage a revolution.

Hi:

Thanks for the idea! I wanted to share how I used it in my eighth grade media literacy class.

I worried that drawing ability for cars would count for more than creativity, so I tried to come up with something simple they could make with just paper, but that would provide multiple opportunities for innovation and improvement.

I brainstormed several things: paper airplanes, place mats, crowns, and settled on bracelets. They were to be jewelry companies.

I gave each group (4 students in a class of 28) a pair of scissors, a pen, scotch tape, and a piece of copy paper.

We did three rounds of capitalism one day with 8-10 minutes for each round of production. They got a new piece of copy paper each round.

I paid them in smarties, so they definitely had incentive to work!

We did three rounds of communism the next day with each company being paid the same amount of smarties no matter what.

Many companies did slack off under communism, but there were some who continued to produce well/innovate, so we had a discussion about intrinsic motivation and how that connects. We talked about the pros and cons of both systems.

What a wonderful idea. Thank you so much!

Sally R.

Sally:

Thanks so much for sharing your result. It’s especially intriguing to see how you adapted the simulation for your class. I also really like the tie in to the intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation discussion.

Glad it worked so well.