If economics ultimately boils down to the study of human behavior, and our students are ultimately human (stick with me for a second here), then economic theory ought to be able to inform the way we teach. In fact, I’d argue that constructivist approaches to education, like Montessori, work for the same reasons that free-markets outperform highly-centralized command economies: freedom (within limits) better maximizes human welfare. I think this applies both to students in aggregate (the entire student population), and to the individual student also, though you probably have to aggregate over time.

What do I mean by Economics

As a study of human behavior economics differs from psychology, sociology and the other social sciences primarily because it uses money as a metric. This gives it a lot more data to play with. The last century has clearly demonstrated the advantages of the “invisible hand” of the free-market over highly-centralized command economies in providing for the broader public good. So what lessons from the study of economics can we apply to education?

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that we should be treating our schools and classrooms as businesses. We’re not trying to maximize profits for a firm (via test scores or however else that might translate to education), we’re trying to maximize the welfare of our students, which I take to mean, helping them achieve their full potential.

Command-and-Control

As we’ve seen in our studies of economics, flexible, market-based approaches are much better (more efficient) at achieving goals that the command-and-control, dictatorial model. The evolution of EPA’s approach to regulating pollution is an excellent example of how a federal agency learned to employ the experience of economics to better achieve a public good.

In the 1960’s and 70’s, rivers catching on fire, smog, and books on the invisible consequences of pollution, like Silent Spring, inspired the environmental movement and spurred the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The EPA’s job was, and is, to enforce the laws that reduce pollution and protect environment. In the beginning, they did this by telling industry and companies what to do: the EPA mandated strict limits on the emissions from factories; and power plants were required to install the “best available technology” to reduce pollution. These approaches sound good, and are certainly necessary for pollutants that are dangerous to places close to where they are emitted, but they can be expensive, encouraging people to look for loopholes in the rules so they also become expensive to enforce.

You get the same problems with long, detailed lists of rules in the classroom. Students try to circumvent the letter of the law, rather than adhere to the spirit of the rules. “No iPods allowed,” is forced to evolve into “No Personal Electronic Devices.” Then come the questions, “What about watches?” and, “What about iPads?” so more rules need to be added to the list. By the end of the week you’re approaching a list of rules approaching the length of the tax code, and still adding more.

In the case of environmental regulation, to deal with this type of problem, the field of environmental economics emerged. Environmental economists try to figure out how to achieve the pollution reducing outcomes that everyone wants in the most economically efficient way possible. More efficiency means lower costs to society. They found that there are usually quite a number of ways to achieve the environmental objectives, using the principles of the free market, that are much more efficient than the command-and-control approach the EPA had been using.

Economists like to use mathematics. There are lots of supply and demand curves, and lots of derivatives, which tend to force some over-simplification (in much the same way that your textbook supply and demand curves are almost invariably straight lines). However, sometimes simple models can lead to a better understanding of how people in societies work.

Cap and Trade

In the 1980’s coal burning factories and power plants were churning out a lot of pollutants. One of these, sulphur dioxide (SO2) would react with rainwater and to create sulphuric acid, which would fall as acid rain. Acid rain was a huge problem because lots of plants and animals living in lakes, streams and forests were finding it hard to adapt to the increasing acidity of their environment. Furthermore, more acidic rainwater was damaging the paint on people’s cars and dissolving limestone statues and buildings.

So the EPA implemented a Cap and Trade program. They had a good idea of how much SO2 was being released into the atmosphere, and they know how much they wanted to reduce it by, so they started to issue companies permits to pollute.

The trick was that EPA would only give out permits equal to the total amount of SO2 emissions they wanted, and every year they would reduce the amount of permits until they reduced the pollution enough to resolve the acid rain problem.

Now all the companies that polluted SO2 had to either buy a permit or stop polluting. If they could easily reduce their pollution, a company might have extra permits that they could sell to a company that was having a harder time. In theory, some companies could even buy up permits from other companies and increase their pollution. But since the EPA was only giving out so many permits, whatever happened the total SO2 pollution was still going down.

Doing it this way let the EPA set the goals and let the market for pollution permits allocate how the actual pollution reduction got done. Since the permits could be sold, this encouraged the companies that could easiest reduce their pollution to do so, resulting in a reduction in pollution at the lowest cost.

It also meant that companies were now starting to pay for the environmental damage they were doing. Acid rain is a regional problem so it’s hard to say that your pollution from your factory in Ohio is specifically causing the acid rain here in my forest in Vermont. The atmosphere was being treated as a common dumping ground.

Cap and trade is not without its problems, however, at least in this case, it worked extremely well.

The Innate Desire to do the Dishes

Montessori believed that children have an innate desire to learn. We’ve seen how easily praise and rewards can damage that internal drive. I have, however, found it hard to identify my student’s innate desire to do the dishes. They may want a clean environment, they may have been trained since pre-kindergarten to clean up after themselves (restore their environment), but their is quite often a reluctance to doing it themselves.

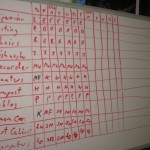

The relationship to the pollution issue is startling to think about at first, but really the issues are the same. After struggling for quite a while to get everyone to do their classroom jobs, recognition of the parallel between my job and the EPA’s lead me to thinking about creating the Job Market Trading Board. Students can trade jobs and when they do it, but in the end, the jobs get done. I remain impressed at how well it has worked.

The basic principle is more general though: set the goals and let the students figure out the best way to accomplish them.