I’m often surprised by how late my student get to sleep. It can range from 9 pm to past midnight, and I’d love to be able to recommend to parents that their kids should go to sleep earlier. However, the research on sleep patterns among adolescents shows the issue is a bit more complex.

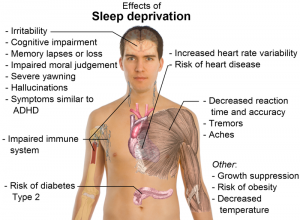

First off, adolescents should get about 9 hours and 15 minutes of sleep per night according to Bill Dement (1999) who guided a lot of the foundational studies on sleep patterns. Not getting that much sleep, especially on recurring basis, results in sleep deprivation, which is well known to have a negative effect on school performance (Mayo Clinic staff, 2009). And a lot of adolescents are getting less than 9 hours.

But just setting earlier bedtimes may not work. Late in puberty adolescents’ biological clocks change, creating a window in the evening when it is difficult to get to sleep:

“[M]any adolescents … actually feel great at night and, for many of them, that makes it harder for them to even consider trying to go to bed earlier. So they’ll say goodnight to Mom and Dad and they’ll go into their rooms and read or play video games or talk on the phone. And they’re perfectly content and happy doing that, because they’re also at a phase where it’s easy for them to become aroused and stimulated by these activities. So it really does turn into a Catch–22. When people just say, “Well, all they have to do is go to bed earlier,” well, they really can’t go to sleep earlier necessarily.” – Mary Carskadon in Frontline (2002).

However, Mary Carskadon‘s research (and others) has shown that despite the changes in the biological clock that occur during adolescence, children still need the same total amount of sleep, even if they’re not getting it.

reduced habitual sleep time reported by adolescents may be related more to environmental factors (social, academic, and peer pressure) than to declining “need” for sleep. – Carskadon et. al. (1980)

So the fact that adolescents are not getting enough sleep is likely because of how society has changed. An interesting Brazilian study found that children living in homes without electrical lighting had significantly earlier sleep times than those with electricity (Peixoto et. al., 2009). Another study found that sleep deprivation was related to the amount of multitasking students did at night.

So to get enough sleep, we need to adjust the environment (wilderness training anyone?). The Mayo Clinic has a useful site on teen sleep. They recommend:

- Adjust the lighting. As bedtime approaches, dim the lights. Turn the lights off during sleep. In the morning, expose your teen to bright light. These simple cues can help signal when it’s time to sleep and when it’s time to wake up.

- Stick to a schedule. Tough as it may be, encourage your teen to go to bed and get up at the same time every day — even on weekends. Prioritize extracurricular activities and curb late-night social time as needed. If your teen has a job, limit working hours to no more than 16 to 20 hours a week.

- Nix long naps. If your teen is drowsy during the day, a 30-minute nap after school may be refreshing. But too much daytime shut-eye may only make it harder to fall asleep at night.

- Curb the caffeine. A jolt of caffeine may help your teen stay awake during class, but the effects are fleeting. And too much caffeine can interfere with a good night’s sleep.

- Keep it calm. Encourage your teen to wind down at night with a warm shower, a book or other relaxing activities — and avoid vigorous exercise, loud music, video games, text messaging, Web surfing and other stimulating activities shortly before bedtime. Take the TV out of your teen’s room, or keep it off at night. The same goes for your teen’s cell phone and computer.

Finally, I’m still thinking about what this means for students taking naps during personal world time. I’m not usually opposed to the occasional short nap, but just how much does this help?