Last year, for an IRP, one of my students did the experiment measuring the speed of light (and the wavelength of the waves) using marshmellows in a microwave. The video above (via Gizmodo) shows the pattern of the microwaves using some neon lights embedded in plastic. The video below, from MythBusters, shows superheated water in action; something I demo every time I make tea-water in the microwave.

Author: Lensyl Urbano

Writer’s Resources

MediaBistro has a series of posts for National Novel Writing Month to inspire and assist the serious writer.

Tips and links range from how to start a writing bible, to the correct writing posture. I’m partial to tip on how to turn your computer into a typewriter, although it’s something that’s never worked for me:

The free Q10 program will convert your distracting computer into an old-fashioned typewriter–focused by real typing sounds and disconnected from the Internet.

–Boog (2010) in GalleyCat

Life on Mars

Discover Magazine has a great article summarizing the evidence for life on Mars. It’s long because it goes into a lot of detail examines quite a variety of possibilities, but it ties quite nicely in with the questions we are asking about what is life and where it can be found.

The article also mentions a study titled, “The Limits of Organic Life in Planetary Systems” produced by the National Research Council for NASA. It can be found for free online, with an associated podcast that much more accessible to middle schoolers. The report is extremely open to the possibility that extra-terrestrial life exists, and could exist even without water and might even be silicon based.

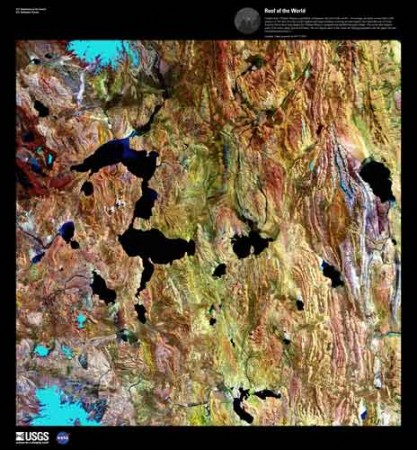

Artistic satellite views of the Earth

For the geography nerds, but perhaps also for those with an appreciation of the natural beauty of the world. The US Geological Survey has a series of satellite pictures chosen just for their sheer beauty.

The Landsat satellites that take these pictures usually photograph in more than just the human-visible color spectrum. For many geologic and environmental purposes, different infra-red wavelengths are often better for seeing details on the Earth’s surface. The USGS has a nice primer on the Landsat program. Many of the color images posted here were reconstructed from different color bands.

The resulting images can be exceptionally beautiful and somewhat surreal. I like that there is an abstract surface beauty, divorced from the content, meaning and understanding that a closer analysis of the images yields to the eye of the trained observer: delicate swirls of algae might be signs of eutrophication to a biologist; dendritic deltas tell the geologist about sediment load, offshore currents and mass balance.

Environmental imperatives

NPR had facinating story recently about unlikely groups working together. It’s about a town in Nevada that banded together to save a toad from going extinct. The groups working together include environmentalists and the Saving Toads thru Off-Road Racing, Mining and Ranching in Oasis Valley (aka STORM-OV).

Adolescent humor?

And laughter without philosophy woven into it is but a sneeze at humor. Genuine humor is replete with wisdom, and if a piece of humor is to last, it must do two things. It must teach and it must preach – not professedly. If it does those two things professedly, all is lost. But if it does them effectively, that piece of humor will last forever – which is 30 years.

– Mark Twain

The term is not loaded with connotations of wisdom and wit, but “adolescent humor” is inescapable in the middle school. The question is, “What to do about it?”

With the recent furor over Mark Twain’s autobiography, which was embargoed for 100 years, I’m taking my cues from him (see above), especially since I like this philosophical approach to life in general.

I suspect it has much to do with the development of abstract thinking. During adolescence we develop a much greater ability to see and to create subtexts. With humor, the philosophy is behind the scenes, which makes it deep and resonant, but harder to see.

Background context is also important with humor, especially parody and satire: however, just because students can’t reference Plato or Socrates (the philosopher not the footballer), does not mean they don’t have their own cultural markers they can critique. Getting past “adolescent humor” means adding layers.

I am, of course, no expert on humor. This cycle I’m working with the mentor author group and my project is focusing on humorous dialogue. I have no high hopes, but I’m giving it the old college try.

None of this made it any easier last week, when I had to explain editorial cartoons. Our class is trying something new for a newsletter, a newspaper style. I vetoed Garfield-like strips as too simple, and insisted that their cartoons had to make a statement first and aim for humor second. The first student who volunteered for the job gave up after a couple hours of pulling his hair out. I think I’ll try showing them some editorial cartoons if I can find a good website. We’ll see how it goes.

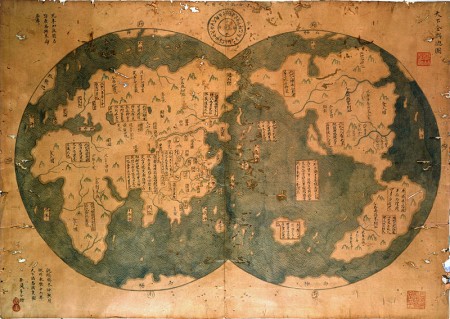

Chinese exploration

Most of the exploration we studied this cycle were European expeditions. One group wanted to do something a little different, so I suggested they look in to Chinese explorations of other parts of the world. There was much Chinese commerce across the Indian Ocean, and in a non-Christian twist on the “God” theme for exploration, the Chinese brought Buddhism back from India in the third century AD (we’re studying exploration under the themes of God, Gold and Glory).

Another interesting aspect of research into Chinese exploration is the rather controversial work by Gavin Menzies that suggests that great Chinese fleets explored the Americas and circumnavigated the globe in the 1420’s, a long time before Columbus and Magellan.

There is a lot of evidence that there was no such Chinese expedition, but it’s a fascinating hypothesis and, in a way, very similar to the All About Explorers project: although Menzies’ work is not an intentionally educational hoax. Indeed, it is much more subtle and much more detailed. My favorite line of critique asserts that Menzies’ books, “.. may well prove to be the Piltdown Man of literature.” I don’t know if I’ll have the time to try to unpack that one for my students.

Northwest Passage

The poignancy and romance of exploration are distilled in Stan Rogers’ ballard “Northwest Passage“.

Ah, for just one time I would take the Northwest Passage,

To find the hand of Franklin reaching for the Beaufort Sea;

Tracing one warm line through a land so wild and savage

And make a Northwest Passage to the sea.

–Stan Rogers (1981) from Northwest Passage.

The Bounding Main website has the lyrics, including footnotes about Franklin and the others mentioned in the song, as well as major geographic features like the Davis Strait and the Beaufort Sea.

History and art collide. The music sticks in the brain then seeps down to catch the throat. I think this is a great way to get into (spark the imagination about) Artic exploration.

The next step is, of course, Shackleton and The Endurance.