We just used my sailing game, Mariner AO, to help wrap up the group presentations on the European exploration of the Americas, and it worked wonderfully!

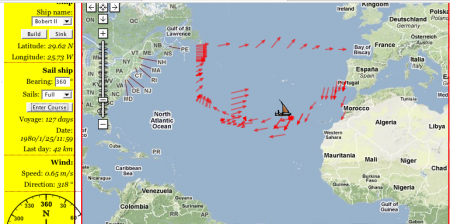

The small groups did their presentations timewise, starting with the Vikings (don’t ask me about Leprechauns), then the Spanish, the French (don’t ask me about giant sharks and flying pigs), and finally the English. At the end, we had half an hour left, but instead of just tying it together with a graphic organizer, I wanted to show them Mariner AO because the North Atlantic wind circulation ties in so wonderfully well with the pattern of colonization.

I started trying to show it off as a group, having them tell me which direction to sail the ship to get to the Americas. As you could probably predict that didn’t work particularly well. Everyone was yelling out directions at cross-purposes; however, it did give me the chance to show them all how the game worked.

Even with all the confusion the group seemed to like the game. Someone even suggested, “Why didn’t we do this for group work.” And I though, “Why not?” So the class broke apart for 25 minutes to see who could discover America first.

There was a lot of excitement in the room. I offered them extra points for the team that reached America first. They all know how empty that reward is by now so I think most of the excitement really came from being able to play a game with a little bit of competition.

The website still has a few bugs, especially on our older computers, but it worked. Three of the four groups reached the Americas, though two of them landed on the Canadian coast. The third group may well have ended up there as well, but I dropped a hint about Columbus’ route that sent them sailing into the Caribbean.

At least two kids planned on trying it at home. I had to pry one of the groups away from the computer so they could get their end-of-the-day jobs done on time.

We took screen captures of routes they took, and tomorrow we’ll put it all together, talk about the trade winds, what Columbus knew, and why the Iberians colonized South America while the French and English ended up mostly in the North.