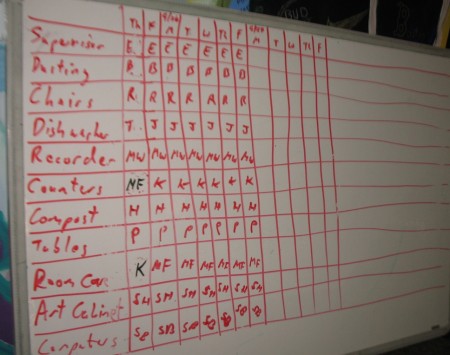

Sally, our school’s business manager, was kind enough to come in last month to help the financial department of the student run business organize its books. It was long overdue. We’d been improving our record keeping over the last couple years, but now we have much more detailed records of our income and expenses.

This is great for a number of reasons, the first of which is that students get some good experience working with spreadsheets. We use Excel, which in my opinion is far and away Microsoft’s best product (I’ve been using OpenOffice predominantly for the last year or so because, it improved quite a bit recently, and I’m a glutton for certain kinds of punishment.) I’ve been surprised by how many students get into college unable to do basic tables and charts, but hopefully this is changing.

The second reason is that the Finance committee can now use the data to give regular reports; income, expenses, profit, loss, all on a weekly basis. I expect the Bread division to benefit the most, since it has regular income and expenses, offering students frequent feedback on their progress. We’re now collecting a long-term, time-series data-set that will be very nice when we get to working on statistics in math later on.

In fact, we should be able to use this data to make simple financial projections. Linear projections of how much money we’ll have for our end-of-year trip will tie into algebra quite nicely, and, if we’re feeling ambitious, we can also get into linear regressions and the wave-like properties of the time series of data.