My middle school class tried DNA extractions from dried split peas and cheek cells for a lab this week, and the experiments went rather well.

Split Pea DNA

For the split peas, we followed the Learn.Genetics lab. I blended the peas in some salty water at the front of the class (“Don’t you need a lid for that blender?”), and filtered it. This gave about 120 ml of filtrate. Then I added in 3 tablespoons of dish soap to the filtrate. The soap to breaks down the cell membranes and nuclear membranes because they are made of lipids (fats).

I shared out the resulting green liquid to the four groups. Each student was able to get a fair amount into a test tube so they could complete the lab as individuals.

Disintegrating the cell and nuclear membranes with soap exposed the DNA, but the long DNA molecules tend to be coiled up around proteins. Each student added a pinch (highly quantified I know) of meat tenderizer to their test tube to break down the protein and allow the DNA to uncoil. Enzymes are biological catalysts, large complex molecules that accelerate chemical reactions, the breakdown of proteins in this case, without breaking down themselves, so only a little is needed.

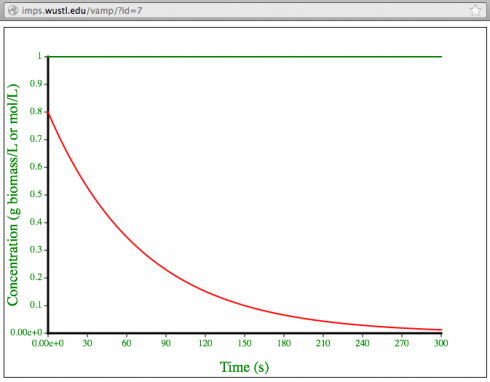

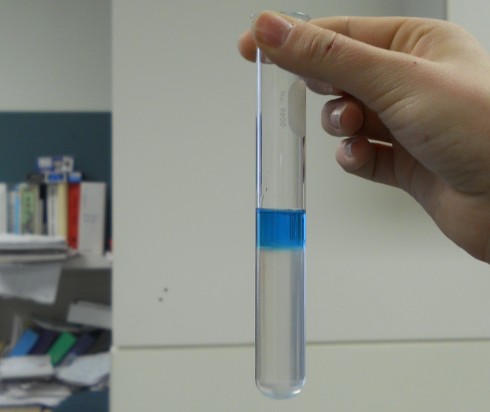

Finally, each student carefully poured rubbing alcohol into the test tube. I had to demonstrate how to tilt the test tube while alcohol was being poured into it so that the alcohol would not mix in with the pea soup but, instead, form a layer at the top, since the alcohol is less dense than the suspension of split peas in salty water.

If it was done carefully enough, the DNA would precipitate at the boundary between the two liquids. If not, the DNA would still precipitate, but it would be mixed in together with the green soup and be harder to distinguish.

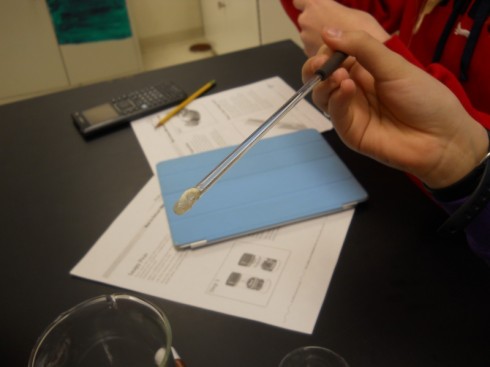

Either way, however, students could see the long strands of DNA, and fish them out with glass rods.

Human DNA

The human DNA extraction procedure is well demonstrated by the NOVA video. One student who missed the split pea lab did this experiment instead because it’s faster. It does not require blending to crush the cells, nor does it need the meat tenderizer enzyme.

Although this procedure produces a lot less DNA — after all, you’re only getting a few loose cells from the insides of your cheeks — the strands are still visible. And it’s YOUR DNA.

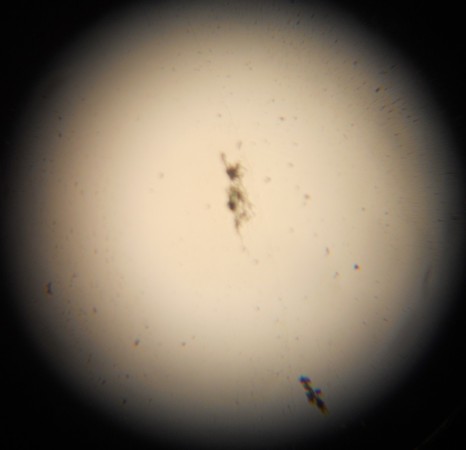

Since I instructed the class on how to use the microscopes last month, one student wanted to see what his DNA looked like under the microscope. An individual DNA molecule is too small to see, but the strands we have are bunches molecules that are visible. They just don’t look like very much.