The problem with global climate change and agriculture not only that it will probably make it harder to grow crops as the continents dry, but also that where you can grow thing will also change as ecological regions shift. Places where there are long traditions of crops such as sugar maples and cranberries will have to adapt, and often, adapting isn’t easy. This article from Marketplace looks at cranberries in Massachusetts.

Category: Biology

Eating Frankenfish

Ian Simpson has an interesting article on the movement to reduce the numbers of the invasive snakehead fish more appealing to restaurants and their customers.

[Snakeheads have] dense, meaty, white flesh with a mild taste that is ideal for anything from grilling to sauteing.

…

[But] the fish are air breathers that can last for days out of water. Even when gutted and with their throats cut, they gape for breath, said John Rorapaugh, director of sustainability and sales at ProFish, a Washington wholesaler.

“Once they get to mature size, they are on top of the food chain and are ravenous,” he said.

…

Josh Newhard, an expert on the snakehead with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said it was too early to say what the snakehead’s long-term impact would be on its invaded environment. … “The potential is really high for them to impact other fish species. The fact that people want to remove them from the system is really good,” he said.

–Simpson (2012): U.S. chefs’ solution for invading Frankenfish? Eat ’em from Reuters via Yahoo! News.

My middle-school students are reading Janet Kagan’s short story, “The Loch Moose Monster” as part of our discussion about genetics, ecology and educational environments. This article makes a nice complement.

Invasive Species on Campus

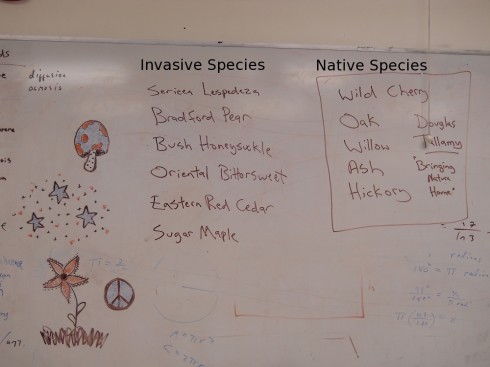

Last Friday, we were lucky enough to have a horticulturalist, Scott Woodbury, visit the Environmental Science class. Scott teaches the Native Plant School at the Shaw Nature Reserve, and spends a lot of effort dealing with invasive species.

The extent of the problem on our campus was quite sobering. The invasive trees, shrubs, and vines displace native plants, and animals as well because the native fauna are not adapted to them. A native elm might support somewhere around 300 species of caterpillar, while an imported bradford pear might have just a few; Douglas Tallamy has a good book, Bringing Nature Home, on the subject.

The bradford pears are quite pernicious. They were once favored by landscapers because of their beautiful spring flowers and brilliant fall colors. However, the birds spread their seeds far and wide, and now bradford pear saplings can be found all over the campus. They tend to do better in the grassy areas at the sides of the roads, as well as on the slope overlooking the school that’s still in the early stages of succession. The saplings can be cut down with hand saws, and I doubt anyone would notice that they were gone, but it’s probably going to be tricky getting permission to take down the half dozen mature trees on the front lawn that were planted when the school was built.

The dark secret about the oriental bittersweet vine that’s attacking the trees along the creek, is that they probably came from the Shaw Nature Reserve. Apparently there was a mistake at one of their sales, and one of our teachers bought the wrong species of bittersweet. Cutting the vines that are growing up the tree trunks should slow them down.

Sericea lespedeza has pretty much taken over the slope above the school. This herb was imported for erosion control but was found to be extremely hard to control. On the plus side, while it does well in disturbed areas like the slope, since it is an early succession species, it will be succeeded by the tree species that are now growing up through it. It’s just going to take a number of years.

At least the bush honeysuckles, which can be found all along the creek, can be hand pulled if they’re small enough. However, we’ve got some pretty big specimens that are much harder to get rid of. They grow fast, leaf-out early, and crowd out the native shrubs.

Interestingly, all these four species are all from Asia. The latitude is similar to Missouri’s so species from that part of the world can thrive here where the climate is similar and they don’t have their native predators and pests. Scott did point out a couple of native species — eastern red cedars and sugar maples — that have become much more aggressive because of all the fire suppression over the last few hundred years, but that’s a story for another time.

Shrimps are not for Wimps

Shrimps are not for Wimps

by Abby ReynoldsOne day I walked into the science class,

I was preoccupied as I looked into the looking glass.

For Dr. Urbano had cooked up a surprise,

And after I wished I was at the car rental Enterprise.

Then I would be able to drive away,

From the disgusting horrors I saw that day.

It started with a metal tray,

With icky rubber a sickly gray.

He brought the probe and scalpel too,

My o my, Sydney turned blue!

Then a smelly smell filled the room,

Making us cough and gag all too soon.

When I saw the shrimp my stomach did flip-flop,

For the color was like that of a caramel lollipop.

I inhaled through my mouth to calm my brain,

Trying not to think how the shrimp was slain.

It helped somewhat until I saw Sydney,

Who was slicing and dicing at a kidney.

She looked up and grinned a big grin,

A smear of blood dripping down her chin.

I will kindly spare you the rest of the story,

For I fear that it gets MUCH too gory!

And there I was thinking that the shrimp dissection had gone rather well.

Snakes on the Ground

An elegant, non-poisonous, eastern garter snake has been hanging around my container garden. On these last few days with the scent of winter in the air, it’s been sunning itself on the warm gravel on the southern side of our building.

Shrimp

Our middle-school dissections have moved on from hearts to whole organisms. This week: jumbo shrimp.

I particularly like these decapods because the external anatomy is simple but interesting, including: eyes on stalks; a segmented body; 5 pairs of swimming legs; 5 pairs of walking legs. The simple, clear layout make them a good subject for students to work on improving the accuracy of their full-scale drawings.

The internal anatomy is a bit harder to distinguish, however, since the organs are relatively small. Most of my students found it difficult to remove the carapace without smushing everything inside the thorax, which includes the stomach, heart, and digestive gland.

The abdominal segments were easy to slice through, on the other hand, and we were able to identify the hindgut (intestine), which runs the length of the back side, and the blueish-colored, nerve cord that is nearer the front (ventral) side.

Under the microscope, you could see little mineral grains in the contents of the gut. Although I did not manage to, I wanted to also mount the thin membrane beneath the carapace on a slide. If I had, we might have been able to see the chromatophores, “star- or amoeba-shaped pigment-containing organs capable of changing the color of the integument” (Fox, 2001).

References

Richard Fox (2001) has a good reference diagram and description of brown shrimp anatomy.

M. Tavares, has compiled some very detailed shrimp diagrams (pdf) (originally from Ptrez Farfante and Kensley, 1997)

Hearts

My middle school class has been looking at organ systems and we’ve started doing a few dissections. We compared chicken and pig hearts last week.

Pig hearts are large and four-chambered like ours, so they should have matched up very well with the diagrams from the textbook. However, real life tends to be messy, which is one of the first lessons of dissection. It was tricky finding all the chambers, and identifying the valves, even when you knew what you’re supposed to be looking for. It is especially difficult, as one of my students noted, because everything isn’t color coded.

Chicken hearts are a bit trickier, because they’re a lot smaller. They also have four chambers, but the main chamber (the left ventricle) is so dominant that it’s easy to assume that there’s only the two (or even just one) chambers.

One student’s interesting observation was that the pig heart was a lot more pliable than the chicken heart. My best guess was that the chicken heart is made of a tougher muscle — it’s denser and more elastic (in that it rebounds to its original shape faster) — because has more work to do: chicken heart rates can get up to 400 beats per minute (Swinn-Hanlon, 1998) compared to 70 beats per minute for the pig.

To get a better feel for the texture, and to engage our other senses in our observations on the hearts, at the end of the dissection, which was conducted in the dining room using kitchen utensils, I fried up some of the chicken hearts with onions for lunch.

Notes

There are a number of nice labs for heart dissections online:

The hearts were purchased at the Chinese supermarket, Seafood City. There seems to be a greater organ selection on the weekends.

Mycorrhiza: Symbiosis Between Fungi and Plants

Symbiosis in action (specifically an example of mutualism):

The Amanita [mushroom] family also includes some of the best-known tree-partnering fungi on Earth. Many of the mushrooms in this family are mycorrhizae — fungi that coil themselves in and around the roots of trees.

The tree provides them with food it makes topside in return for a vastly improved underground absorptive network. This network, made by the many searching filaments of the fungus, brings much more water and many more minerals to the tree than it would otherwise be able to procure for itself.

— Frazer (2012): Deadly and Delicious Amanitas Can No Longer Decompose on The Artful Amoeba Blog in Scientific American.

In fact:

Some plants are “mycorrhizal-obligate,” meaning that they can’t survive to maturity without their fungal associate. Important mycorrhizal-obligate plants in western North America are sagebrush, bitterbrush, and some native bunchgrasses.

— BLM: Mycorrhizal Fungi

This comes from an interesting article by Jennifer Frazer on Amanita mushrooms, which are so symbiotic with their plant hosts that not only do they not decay them, they actually can’t decay them.