Category: Environmental Science

Environmental History of St. Louis Seminar

The St. Louis Zoo is hosting a couple interesting presentations that should be relevant to my Environmental Science class. One, by Andrew Hurle from the University of Missouri, St. Louis, is on environmental history and environmental justice issues in the St. Louis (6pm on Wednesday).

The second is by the sustainability Director in the City of St. Louis Mayor’s Office, Catherine L. Werner.

New York Mayor on Climate

Just a few days after the devastation of Hurricane Sandy, New York mayor Michael Bloomberg considered the role of climate change:

… The floods and fires that swept through our city left a path of destruction that will require years of recovery and rebuilding work. And in the short term, our subway system remains partially shut down, and many city residents and businesses still have no power. In just 14 months, two hurricanes have forced us to evacuate neighborhoods – something our city government had never done before. If this is a trend, it is simply not sustainable.

Our climate is changing. And while the increase in extreme weather we have experienced in New York City and around the world may or may not be the result of it, the risk that it might be – given this week’s devastation – should compel all elected leaders to take immediate action.

Here in New York, our comprehensive sustainability plan – PlaNYC – has helped allow us to cut our carbon footprint by 16 percent in just five years, which is the equivalent of eliminating the carbon footprint of a city twice the size of Seattle. Through the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group – a partnership among many of the world’s largest cities – local governments are taking action where national governments are not.

But we can’t do it alone. We need leadership from the White House – and over the past four years, President Barack Obama has taken major steps to reduce our carbon consumption, including setting higher fuel-efficiency standards for cars and trucks. His administration also has adopted tighter controls on mercury emissions, which will help to close the dirtiest coal power plants (an effort I have supported through my philanthropy), which are estimated to kill 13,000 Americans a year.

Mitt Romney, too, has a history of tackling climate change. As governor of Massachusetts, he signed on to a regional cap- and-trade plan designed to reduce carbon emissions 10 percent below 1990 levels. “The benefits (of that plan) will be long- lasting and enormous – benefits to our health, our economy, our quality of life, our very landscape. These are actions we can and must take now, if we are to have ‘no regrets’ when we transfer our temporary stewardship of this Earth to the next generation,” he wrote at the time.

— Michael R. Bloomberg, 2012: A Vote for a President to Lead on Climate Change in Bloomberg.com.

While NPR has an article on a proposed, multi-billion dollar, offshore barrier to prevent the storm surge.

Since we’re talking about environmental economics at the moment, I played the interview, had my students read the Bloomberg excerpt, and then provoked a discussion of the value of human life with the question, “If the proposed $10 billion project could save 50 lives, would it be worth it?”

To keep the discussion focused I asked them to ignore all the other possible benefits of the barrier.

It’s a really tricky issue to deal with, but we ended up talking about how the U.S. government estimates the monetary value of human life. According to a recent New York Times article, values range from $6.1 million (Dept. of Transportation) to $9.1 million (EPA).

The business community historically has pushed for regulators to put a dollar value on life, part of a broader campaign to make agencies prove that the benefits of proposed regulations exceed the costs.

But some business groups are reconsidering the effectiveness of cost-benefit analysis as a check on regulations. The United States Chamber of Commerce is now campaigning for Congress to assert greater control over the rule-making process, reflecting a judgment that formulas may offer less reliable protection than politicians.

Some consumer groups, meanwhile, find themselves cheering the government’s results but reluctant to embrace the method. Advocates for increased regulation have long argued that cost-benefit analysis understates both the value of life and the benefits of government oversight.

— Appelbaum (2011): As U.S. Agencies Put More Value on a Life, Businesses Fret in the New York Times.

Melting Permafrost and a Warming Climate: Another not-so-Positive Feedback

There’s a lot of organic matter frozen into the arctic permafrost. As the arctic has been warming much faster than the rest of the planet, the permafrost soils are thawing out quite quickly. As they unfreeze, they set up a positive-feedback loop. The warming organic matter starts to decay releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, exacerbating the warming.

To generate the estimates, scientists studied how permafrost-affected soils, known as Gelisols, thaw under various climate scenarios. They found that all Gelisols are not alike: some Gelisols have soil materials that are very peaty, with lots of decaying organic matter that burns easily – these will impart newly thawed nitrogen into the ecosystem and atmosphere. Other Gelisols have materials that are very nutrient rich – these will impart a lot of nitrogen into the ecosystem. All Gelisols will contribute carbon dioxide and likely some methane into the atmosphere as a result of decomposition once the permafrost thaws – and these gases will contribute to warming. What was frozen for thousands of years will enter our ecosystems and atmosphere as a new contributor.

— Harden and Lausten (2012): Not-So-Permanent Permafrost via USGS Newsroom.

Journaling on the River

It was not all dark and stormy on our Outdoor Education canoe trip. The first afternoon was warm and bright; the first splashes of fall color spicing up the deep, textured greens of the lush, natural vegetation. It was so nice that, in the middle of the afternoon, we took a short break, just shy of half an hour, to reflect and journal.

Our guides chose to park our boats at a beautiful bend in the river. Most of my students chose to sit in the canoes or on the sandy point-bar on the inside of the meander, but a few to be ferried across the river to a limestone cliff on the cut-bank of the curve. An enormous, flat-topped boulder had fallen into the water to make a wonderfully picturesque site for quiet reflection for two students. A third student chose to sit in a round alcove sculpted by the solution weathering of the carbonate rock itself.

The cut-bank of a river’s meander tends to be deeper than the inside of the curve, because the water is forced to flow faster on the outside of the bend where it has more distance to travel. This proved to be quite convenient for my students, because it meant that the stream-bed around their boulder was deep enough that they could jump into the water after the hot work of writing while sitting in the sun. And they did.

(From our Eminence Immersion)

Mycorrhiza: Symbiosis Between Fungi and Plants

Symbiosis in action (specifically an example of mutualism):

The Amanita [mushroom] family also includes some of the best-known tree-partnering fungi on Earth. Many of the mushrooms in this family are mycorrhizae — fungi that coil themselves in and around the roots of trees.

The tree provides them with food it makes topside in return for a vastly improved underground absorptive network. This network, made by the many searching filaments of the fungus, brings much more water and many more minerals to the tree than it would otherwise be able to procure for itself.

— Frazer (2012): Deadly and Delicious Amanitas Can No Longer Decompose on The Artful Amoeba Blog in Scientific American.

In fact:

Some plants are “mycorrhizal-obligate,” meaning that they can’t survive to maturity without their fungal associate. Important mycorrhizal-obligate plants in western North America are sagebrush, bitterbrush, and some native bunchgrasses.

— BLM: Mycorrhizal Fungi

This comes from an interesting article by Jennifer Frazer on Amanita mushrooms, which are so symbiotic with their plant hosts that not only do they not decay them, they actually can’t decay them.

Cave Formation in the Ozarks

Rain falls.

Some runs off,

Some seeps into the ground.

It trickles through soil.

Leaching acids, organic,

Out of the leaf litter,

But even without these,

It’s already, every so slightly, corrosive,

From just the carbon dioxide in the air.

Gravity driven,

The seeping water seeks the bedrock,

Where it might find,

In the Ozark Mountains,

Limestone.

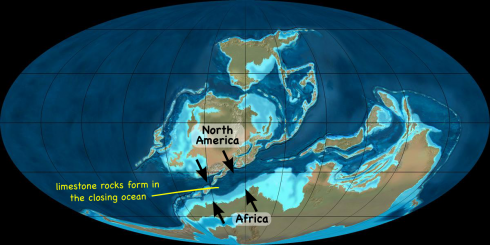

Limestone:

Microscopic shells, of plankton,

Raining down, over millenia,

Compacting into rocks,

In a closing ocean,

As North America and Africa collide,

From the Devonian to the Carboniferous.

Orogenic uplift,

Ocean-floor rocks,

Become mountains,

Appalachians, Ouachitas,

The Ozark Plateau.

Limestone dissolves,

In acid water.

Shaping holes; caves in bedrock,

Where we go,

Exploring.

On the Origin of Species

Perhaps the key reason for the profound influence of Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” is that it’s such a well written and well reasoned argument based on years of study. It is a wonderful example of how science should be done, and how it should be presented. In the past I’ve had my middle schoolers try to translate sections of Darwin’s writing into plainer, more modern English, with some very good results. They pick up a lot of vocabulary, and are introduced to longer, more complex sentences that are, however, clearly written.

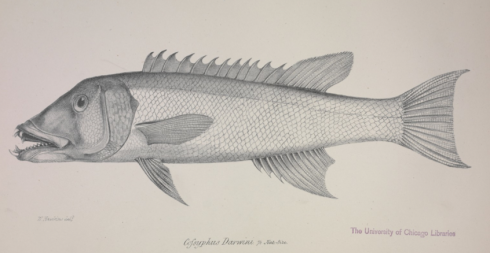

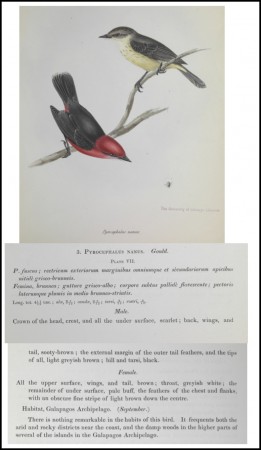

The text of “On the Origin of Species” is available for free from the Gutenberg library. Images of the original document can be found (also for free) at the UK website, Darwin Online (which also includes the Darwin’s annotated copy). Darwin Online also hosts lot of Darwin’s other works, as well as notes of the other scientists on The Beagle, among which is included some wonderful scientific diagrams.

This year, I’m going to have the middle schoolers read the introduction, while the honors environmental science students will read selected chapters and present to the class — this will be their off-block assignment.