Scott Tong has an interesting article in Marketplace about how the U.S. is reducing its carbon dioxide emissions through things like regulation of car fuel efficiency and light bulbs.

Category: Environmental Science

Building a Tree of Life (version 2)

I so liked how the tree of life turned out the last time I tried it, that I did it again this year with a significant improvement in the use of rubber bands.

Students chose organisms and then looked up their classification — Wikipedia quite reliable for this — then they wrote the names down on synchronized chips of colored paper. As usual, they preferentially chose charismatic, mammalian, megafauna, but there was also a squid, and for two people who did not come up with anything themselves, I assigned a plant (elm), and a bacteria (the one that causes strep throat).

The actual color pattern of the chips does not matter, but I used red for Domain, yellow for Kingdom, green for Phylum, pink for Class, red for Order, yellow for Family, green for Genus, and pink for species. The colors repeated, and I liked how that helped organize the pattern of the final result.

In class, using a pin-board, I used push pins to place homo sapiens on the board. I linked the push pins with rubber bands, which makes for a nicer, sharper pattern than using string, and is easier to do.

To get a nice pattern I then asked who had the closest relative to humans. It took a little effort to figure it out, but I decided to go with a degrees-of-separation metric. Basically, I asked them to count up the classification system to see how many levels they’d have to go to get to something their species shared with humans. The closest were at the Class level: mammals.

Then, starting with the students with the lowest separation distance, I had the students come up to the board and add their organism to the growing tree.

Later, during lunch, a student asked me what was the difference between bison and buffalo. I didn’t know, but another teacher pointed out that one was from North America and the other from Africa. So I asked two of my middle schoolers to look up the classification of american bison and water-buffalos, which we subsequently added to the tree, and which got me thinking about how we might use the rate of separation of the two continents to figure out how fast genetic variation develops.

Cranberries and Climate Change

The problem with global climate change and agriculture not only that it will probably make it harder to grow crops as the continents dry, but also that where you can grow thing will also change as ecological regions shift. Places where there are long traditions of crops such as sugar maples and cranberries will have to adapt, and often, adapting isn’t easy. This article from Marketplace looks at cranberries in Massachusetts.

Eating Frankenfish

Ian Simpson has an interesting article on the movement to reduce the numbers of the invasive snakehead fish more appealing to restaurants and their customers.

[Snakeheads have] dense, meaty, white flesh with a mild taste that is ideal for anything from grilling to sauteing.

…

[But] the fish are air breathers that can last for days out of water. Even when gutted and with their throats cut, they gape for breath, said John Rorapaugh, director of sustainability and sales at ProFish, a Washington wholesaler.

“Once they get to mature size, they are on top of the food chain and are ravenous,” he said.

…

Josh Newhard, an expert on the snakehead with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said it was too early to say what the snakehead’s long-term impact would be on its invaded environment. … “The potential is really high for them to impact other fish species. The fact that people want to remove them from the system is really good,” he said.

–Simpson (2012): U.S. chefs’ solution for invading Frankenfish? Eat ’em from Reuters via Yahoo! News.

My middle-school students are reading Janet Kagan’s short story, “The Loch Moose Monster” as part of our discussion about genetics, ecology and educational environments. This article makes a nice complement.

Indoor Clouds

Berndnaut Smilde generates and photographs clouds inside buildings, “He uses a fog machine and carefully adjusts the temperature and humidity to produce clouds just long enough to photograph.”

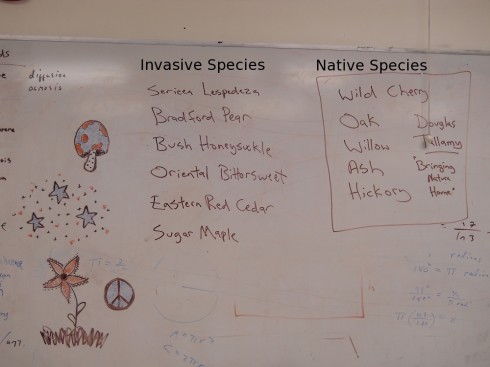

Invasive Species on Campus

Last Friday, we were lucky enough to have a horticulturalist, Scott Woodbury, visit the Environmental Science class. Scott teaches the Native Plant School at the Shaw Nature Reserve, and spends a lot of effort dealing with invasive species.

The extent of the problem on our campus was quite sobering. The invasive trees, shrubs, and vines displace native plants, and animals as well because the native fauna are not adapted to them. A native elm might support somewhere around 300 species of caterpillar, while an imported bradford pear might have just a few; Douglas Tallamy has a good book, Bringing Nature Home, on the subject.

The bradford pears are quite pernicious. They were once favored by landscapers because of their beautiful spring flowers and brilliant fall colors. However, the birds spread their seeds far and wide, and now bradford pear saplings can be found all over the campus. They tend to do better in the grassy areas at the sides of the roads, as well as on the slope overlooking the school that’s still in the early stages of succession. The saplings can be cut down with hand saws, and I doubt anyone would notice that they were gone, but it’s probably going to be tricky getting permission to take down the half dozen mature trees on the front lawn that were planted when the school was built.

The dark secret about the oriental bittersweet vine that’s attacking the trees along the creek, is that they probably came from the Shaw Nature Reserve. Apparently there was a mistake at one of their sales, and one of our teachers bought the wrong species of bittersweet. Cutting the vines that are growing up the tree trunks should slow them down.

Sericea lespedeza has pretty much taken over the slope above the school. This herb was imported for erosion control but was found to be extremely hard to control. On the plus side, while it does well in disturbed areas like the slope, since it is an early succession species, it will be succeeded by the tree species that are now growing up through it. It’s just going to take a number of years.

At least the bush honeysuckles, which can be found all along the creek, can be hand pulled if they’re small enough. However, we’ve got some pretty big specimens that are much harder to get rid of. They grow fast, leaf-out early, and crowd out the native shrubs.

Interestingly, all these four species are all from Asia. The latitude is similar to Missouri’s so species from that part of the world can thrive here where the climate is similar and they don’t have their native predators and pests. Scott did point out a couple of native species — eastern red cedars and sugar maples — that have become much more aggressive because of all the fire suppression over the last few hundred years, but that’s a story for another time.

Hurricane Sandy – Before and After

Living next to Chernobyl

We were talking about environmental disasters, specifically nuclear radiation, and looking at pictures of Chernobyl, when a student asked if anyone still lived there. The city and surrounding region was evacuated, however some 1,200 people returned to their homes. Holly Morris has an interesting article on how “The women living in Chernobyl’s toxic wasteland” survive. Curiously, 80% of the remaining survivors are female.