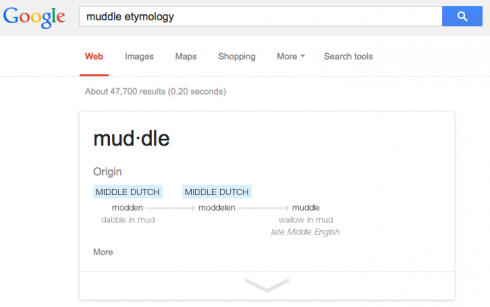

Google search a word with etymology appended and you get the etymology.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

“On a particularly humid day, Abby stood, seemingly staring at the goat that was munching and crunching on oak leaves right in front of her. But really, she was contemplating the rather large fire-ant hill at her feet.” — by A.R.

So begins a rather curious short story, based on real-life events, in which a student faces a crucial, life-changing decision. Somewhat life changing for her, but rather more life changing for a bunch of ants.

This journal entry precipitated an impromptu language lesson that ended with a semi-official apprentice-sentence assignment.

Inside Chris Gayomali’s interesting article on, “How typeface influences the way we read and think” is a bit about an undergraduate student who found that the font he used affected the grades he got on his papers. Turns out that some fonts, Georgia for example, are better than others.

P.S. As the article points out: don’t use Comic Sans.

Paul Brians’ excellent reference, Common Errors in English Usage, is available online.

An example:

LOSE/LOOSE

This confusion can easily be avoided if you pronounce the word intended aloud. If it has a voiced Z sound, then it’s “lose.” If it has a hissy S sound, then it’s “loose.” Here are examples of correct usage: “He tends to lose his keys.” “She lets her dog run loose.” Note that when “lose” turns into “losing” it loses its “E.”

Brians, 2008. Common Errors in English Usage

Aerogramme Writers’ Studio has compiled Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling as well as Neil Gaiman’s Eight Rules of Writing.

Both sets of rules focus on the search for perfection, which, like the horizon, you have to learn to deal with the fact that you’ll never reach to your ideal satisfaction.

William Sieghart does a wonderful question and answer in his Poetry Pharmacy in the Guardian, where he recommends poetry to salve his questioners existential (and not so existential) needs.

For example:

Hi William,

Do you have any poems that clear up a hangover or diarrhoea (preferably both)?

Sounds like you have been living life to the full! Why not congratulate yourself on the good times you enjoyed yesterday rather than being miserable about your today’s predicament? Dryden’s Happy the Man is a good bet:

Not Heaven itself upon the past has power,

But what has been, has been, and I have had my hour.

Another:

It’s a restriction insisted upon by my tenancy – I’m not allowed to keep a dog. I need a poem to help fill the gap left by the absence of a faithful hirsute canine companion. Dr Sieghart, what do you suggest?

Dr Sieghart’s remedy:

I prescribe some of the most famous words in English – ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ by Oscar Hammerstein II. The great consoling line of the title comes after the pain of isolation:Walk on, through the wind

Walk on, through the rain

Though your dreams be tossed and blownWalk on, walk on, with hope in your heart

And you’ll never walk alone

You’ll never walk alone.

One of the neat things that came out of the London Olympics is the Winning Words website that collects sports related poetry in text and video form (full video collection here).

Writing is a process. There might not be one single, best, process, but breaking the process into steps is often useful for new writers trying to find their voice. The following steps come from my Middle School Montessori Training a few years back. While I’m not teaching language at the moment, I would like to get my students to write up their experience in the thunderstorm on the river using at least parts of this process.

As an example of how revision can change a story, I have my two versions of our thunderstorm adventure here and here. They’re aimed at different audiences, but you can see that they came from the same source.