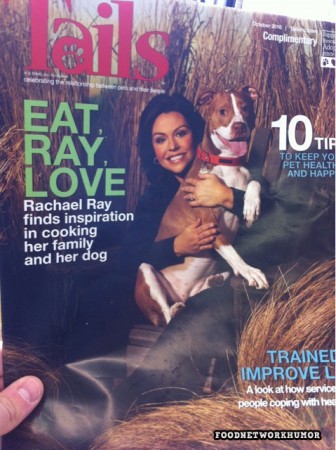

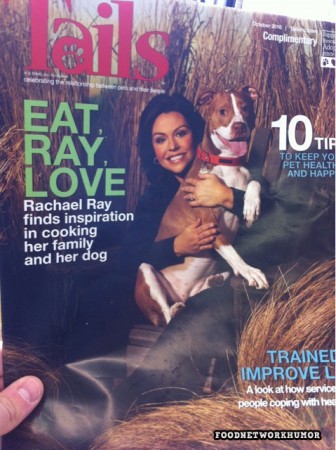

This image, bouncing around the internet, is, unfortunately, a fake. However, it’s still a nice supplement to Eats, Shoots and Leaves when talking about the power of punctuation.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

This image, bouncing around the internet, is, unfortunately, a fake. However, it’s still a nice supplement to Eats, Shoots and Leaves when talking about the power of punctuation.

Poetry can be disjointed, illogical and irrational. Sam Tanenhaus argues that that is why poetry helps us make sense of catastrophes and disasters.

One of the enduring paradoxes of great apocalyptic writing is that it consoles even as it alarms.

This has been, in fact, one of the enduring “social” functions of literature — specifically, of poetry. Narrative prose is less well suited to the task. This isn’t surprising: narrative implies continuity and order — events that flow forth in comprehensible sequence, driven by motive forces of cause and effect. …

But catastrophe defies logic. It faces us with disruption and discontinuity, with the breakdown of order. The same can often be said of poetry itself. It operates outside the realm of “logic.” Rather, it obeys the logic of dreams, of the unconscious. This is especially the case with lyric poetry, with its suggestion of vision and prophecy.

— Tanenhaus (2011): The Poetry of Catastrophe, on the New York Times’ Arts Beat Blog.

Andrew Sullivan, on the Daily Dish, highlights W. B. Yeat’s “The Second Coming,” as being quite apt to the topic. It was written just after World War I (Poem of the Week).

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?— Yeats (1919): The Second Coming, (via Poets.org).

Even if seven editors and seven reviewers, marked it up for half a year, I doubt they’d be able to completely clean up the mess I post to this blog every day (and they’d be full of bitter tears). However, in case they were willing to try, I thought it would be useful to be clear about what I mean by editing and reviewing.

Editing is catching all the grammatical errors, loose spelling, punctuation and so on that the author is liable to miss. Usually it is because he or she is reading what they thought they wrote, not what they actually typed. It might also involve checking citations to make sure they are right. In this case, it does not involve extensive fact checking, though at a real newspaper it would. Partly that’s because facts can be so malleable, but mostly it’s because I believe that making sure the facts are right are the responsibility of the author.

Reviewing is a lot harder, largely because, since it primarily deals with style, it is extremely subjective. I will admit that an awful lot of people are likely to consider my writing boring and atrocious, but I will often disagree. Good review is a process of negotiation. The reviewer tells the author what they like, and why, and what they don’t like, and why. Then, instead of yelling, the author carefully considers the comments and adjusts their piece accordingly. The reviewer then looks it over again and gives the same type of feedback as before. Ultimately, what’s published remains the responsibility of the author; they make the final choice about which comments to accommodate and which to ignore, but good reviewers are invaluable if used well.

So, if you see a tag at the bottom of a post saying “Reviewed by So and So”, or “Edited by So and So”, or even, “Reviewed and edited by So and So”, please spare them a moment’s thought because they’re not an easy or trivial jobs. This is especially true for a blog where the author sets themself the task of posting something every day, and finds it hard to stop writing once they’ve started. Even when they know they should. Like now.

I used my notes and the Keynes versus Hayek music video as part of our reading this week. As usual, half the class tried skipping directly to the video, but it became pretty clear, as I suspected it would, that they didn’t understand what was going on if they had not read the notes.

We’ll be discussing the video tomorrow when we try to wrap up the week’s work, but, as one student mentioned, it can be a little hard to figure out the words in the rap. Fortunately, the Econ Stories website has been updated to include the lyrics.

Even without the lyrics, however, I really like that you can get a good idea about the competing economic theories solely from the video itself, since it’s just a very detailed extended metaphor. It’s so chock full of symbols that it could probably be used to supplement the Calvin and Hobbes comic strip in our language lessons on finding symbols in texts.

Oliver Miller responds (warning: harsh language) to advice given by writers in the Guardian on how to be a writer.

The key thing he mentions, to which all his other advice builds, is the need for good, constructive peer review.

So you need to surround yourself with fellow writers who are supportive but also honest. Some people will tell you that your writing is always good. These people are lying. And some people will tell you that your writing is always bad. These people are also lying. …But a few rare people will point out the stuff that they like, call you out on some of the dumb [stuff] that you’re writing, and gently but forcefully suggest ways to make your dumb [stuff] better [my italics]. Treasure these people. Learn to recognize them. These people are your only hope.

— Miller (2011): How to be a Writer

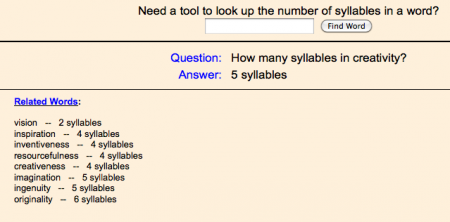

If you need a little help finding how many syllables are in a word so you can use it in your haiku, there’s the How Many Syl.la.bles website.

It also suggests related words if you need a differently-syllabic synonym.

Where disciplines meet

creativity emerges

from the shaking chrysalis

My students are working on poetry this cycle and I’m having them each memorize and present each of the different types of poems we’re covering.

Jim Holt suggests memorizing poems slowly over time:

… the key to memorizing a poem painlessly is to do it incrementally, in tiny bits.

— Holt (2009): Got Poetry?

But I very much like John Hollander’s advice to use the rhythm of the poem to help with memory:

It is partly like memorizing a song whose tune is that of the words themselves.

–Hollander (1995): Committed to Memory

Another approach, which worked for Michael Weiss, was to type out pairs of lines in a word processing program.

It may take about ten repetitions before a couplet is committed to memory, but as you gain experience, they’ll come faster than that.

–Weiss (2009): How to memorize a poem

All of the essays cited above also make persuasive arguments for why anyone should memorize poems. Ultimately, it comes down to the fact that poems in memory are readily available for reflection. You get a feel for the rhythm and musicality, and you get to look at the words in different ways as you turn them around in your mind, playing with their meanings.

Finally, my students have become pretty good at presenting poetry, partly because they’ve seen Shake the Dust, but mainly because of our doing poetry every morning. Good presentations in the past have ratcheted up the quality of the presentations we’ve been seeing.

We’ve already started on haikus, but next week my students will be presenting sonnets. So far, things look promising.

Well, I’ve made sure that everyone who wants one has a blog, and I’m still finding that the girls are the ones who’re updating them while the boys are not.

This is a small class, so we can’t have any statistical confidence in this observation, but for now at least, the trend continues.

I have also noticed that some of my bloggers are using their Personal World time to blog. I did not require this, or even suggest it, but I think this is great because they’re doing exactly the type of self-reflection that Personal World is intended to elicit.