Science is, at its core, hypothesis testing. To learn science learn the scientific method: figure out the precise question to solve (as best you can); come up with an answer you think might work (hypothesis); test it; and repeat as necessary while modifying the hypothesis. Almost all science experiments for middle school through college involve following a set of instructions in the lab manual. Only in independent research projects do students actually go through the scientific process and then it’s difficult because they don’t have the experience.

Part of the problem is that it takes time. Time to muddle through the though process of trying to figure out what exactly is a tractable question to solve. Time to come up to with a reasonable, testable hypothesis. Time to figure out how to test it. Time for iterating through the process again, although, once you’ve set up your experiment the first time doing it again and again is not that hard or time-consuming.

With our Montessori Middle School’s six-week cycle of work, and even with the two weeks dedicated to the Natural World, students should be possible to get through this process for at least one problem. They would probably have to dedicate the two weeks to a single problem/experiment and it would probably be terribly slow in the beginning.

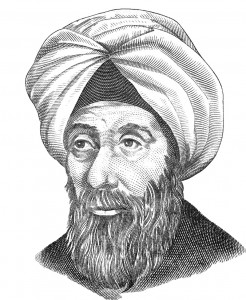

To discover the truth about nature, Ibn a-Haitham reasoned, one had to eliminate human opinion and allow the universe to speak for itself through physical experiments. “The seeker after truth is not one who studies the writings of the ancients and, following his natural disposition, puts his trust in them,” the first scientist wrote, “but rather the one who suspects his faith in them and questions what he gathers from them, the one who submits to argument and demonstration.” – Steffens (2008) (Ibn Al-Haytham: First Scientist)