It was not all dark and stormy on our Outdoor Education canoe trip. The first afternoon was warm and bright; the first splashes of fall color spicing up the deep, textured greens of the lush, natural vegetation. It was so nice that, in the middle of the afternoon, we took a short break, just shy of half an hour, to reflect and journal.

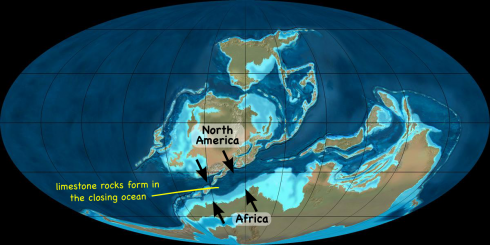

Our guides chose to park our boats at a beautiful bend in the river. Most of my students chose to sit in the canoes or on the sandy point-bar on the inside of the meander, but a few to be ferried across the river to a limestone cliff on the cut-bank of the curve. An enormous, flat-topped boulder had fallen into the water to make a wonderfully picturesque site for quiet reflection for two students. A third student chose to sit in a round alcove sculpted by the solution weathering of the carbonate rock itself.

The cut-bank of a river’s meander tends to be deeper than the inside of the curve, because the water is forced to flow faster on the outside of the bend where it has more distance to travel. This proved to be quite convenient for my students, because it meant that the stream-bed around their boulder was deep enough that they could jump into the water after the hot work of writing while sitting in the sun. And they did.

(From our Eminence Immersion)