It’s remarkable how interest drives motivation and motivation gets things done. We’re in an intercession right now and ten students signed up with me to do a biological survey of the school grounds. With a small creek on one side, and a fairly tall ridge on the other, the school has a nice variety of biomes.

Now, to be clear, I’m not a biologist. In fact, that’s why I was so interested in the biological survey. Everything in this area is new to me. But it also means that I approached this project as a novice. Mrs. E. was nice enough to lend me a veritable library of reference books, covering everything from the wildflowers of Missouri to the amphibians of the mid-West, but she was off teaching another batch of students how to cook, so I was on my own.

All the students in the group were volunteers, but a fair chunk of them just wanted to get outside, even though it was overcast and threatening rain. To get the students more engaged I let them choose either the environment they’d like to survey, or the types of organisms they’d like to specialize in. I also gave them the option of working independently or in pairs.

The Creek

One pair choose to canvas the small creek that runs past the school. I’d set a minnow trap the night before to collect fish for our tank, and they hauled that in. The stream water was somewhere around 14°C, while our tank was closer to 23°C, so, to prevent the fish from going into thermal shock, we left the minnows in a bucket so it could, slowly, thermally equilibrate. They monitored the temperature change with time, and I think I’ll use their data in my physics and calculus classes.

They also collected a pair of amphibians, which we photographed and then released. They tried to catch some crawfish, but were unsuccessful, despite the fact that one of them searched for “how to catch crawfish” on their phone; unfortunately they did not have time to follow the detailed video instructions they found on the web that described, in detail, how to build a crawfish trap.

Trees and Shrubs

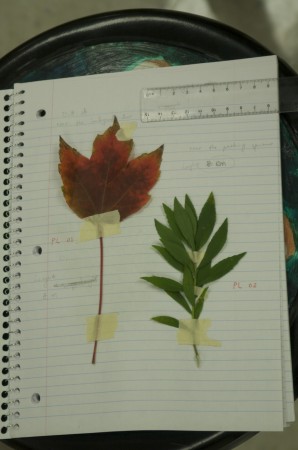

Because of the incipient rain, we did not take our reference books out with us. Instead, we collected leaves and sketched bark patterns so we could do our floral identification later.

A number of students really got into that. So we have a fairly large collection, though almost all of which come from the riparian area that bounds the creek. I would have liked a broader survey, but we only had so much time.

Mushrooms

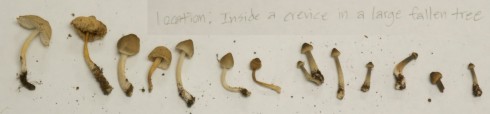

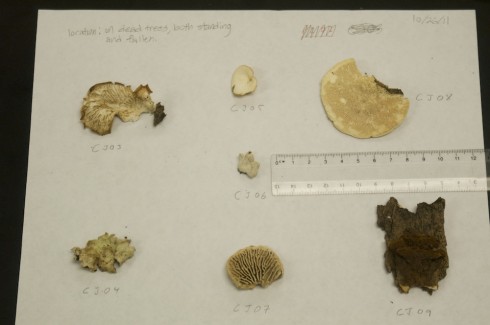

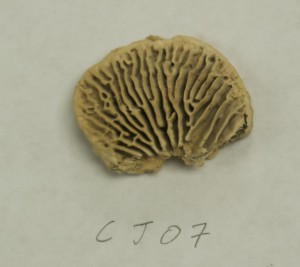

More than a few students were interested in looking for mushrooms – even one of the tree specialists came back a mushroom sample – but one student really got into it, canvasing all the dead logs from the creek, through the meadow, and up past the treeline on the side of the hill.

And we now have quite the collection of fungi. They’re as yet unidentified, but they’re elegant bits of biota. Our fungi specialist is interested in coming back in and sketching them.

Identification

We had two hours. Not even enough time to do a complete survey, so we barely got started on identification. It will probably go slowly.

While our methods were not systematic, and our coverage of the grounds incomplete, this exercise was a good start to cataloging the local biology. I don’t know if I’ll be able to expand on the survey any time soon, but this type of project would be a great for middle school science next year when we focus more on the biological sciences, particularly on taxonomy.