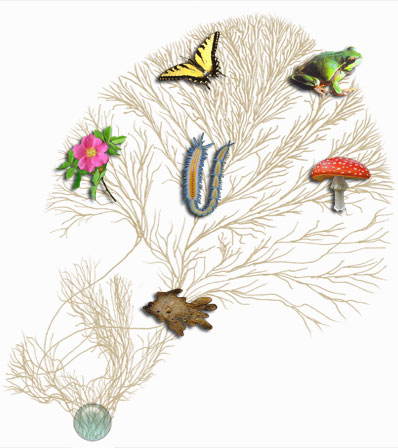

ENSI has a set of great labs that can be used all the way from the middle school to the university level. They deal with the nature of science, the origin of life, evolution and genetics/DNA. (Thanks again Anna Clarke for the link.)

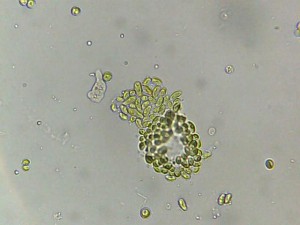

I’m thinking that the Creating Coacervates lab, the only one on the origin of life section, might fit into my orientation cycle plans. Coacervates are small, microscopic blobs of fat (lipids) that look like, and have many of the same properties as cells, amoebas in particular. They can be produced with simple chemicals. One of the key things I’d like to start the year with, is the idea that:

complex life-like cell-like structures can be produced naturally from simple materials with simple changes. Flammer, 1999.

These abiotic blobs can be compared to the protozoans in a water droplet sample while we learn how to use the microscopes. It also ties into the Miller–Urey experiments that produced amino acids using electricity and simple compounds: water, methane, ammonia and hydrogen gas. The Miller-Urey experiments will pop up later when we read Frankenstein.