Dobbie and Fryer (2011) investigate the key things that make for an effective school. Effectiveness is based on test scores, which is a significant caveat, but most of their results seem reasonable.

- Frequent feedback for teachers about their teaching from classroom visits,

- Longer teacher hours, (10+ hours per week)

- Middle school teachers at better schools worked over 10 hours a week more than lower performing schools.

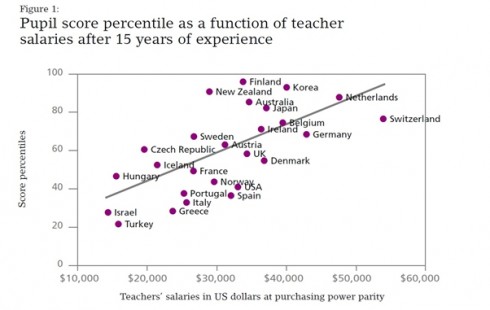

- Interestingly, salary had no discernible effect. It seems that the teachers did not even get paid more for putting in the extra hours. The willingness to put in these extra hours without extra pay implies a different philosophy and culture among the teachers of the “more effective” schools.

- Data driven instruction – more effective schools “adjust tutoring groups, assign remediation, modify instruction, or create individualized student goals,” based on frequent feedback from interim assessments.

- Feedback to parents – better schools have more frequent communication with students’ parents

- High-dosage tutoring – The better performing schools were found to be more likely to offer tutoring where, “the typical group is six or fewer students and those groups meet four or more times per week”,

- Increased instructional time – about 8% more hours per year

- A relentless focus on academic achievement

- This was assessed with a survey of principals. Those who put, “a relentless focus on academic goals and having students meet them” and “very high expectations for student behavior and discipline” as her top two priorities (in either order) scored higher on this assessment of the rigor of school culture.

- I have serious reservations about this result. If the key focus of the school is on doing well on tests (as their “academic goals”) they should do better on the tests. This is certainly a good way to score better on standardized tests, but it has serious, negative implications when it comes to creating intrinsically motivated students.

These results come from comparing charter schools in New York City.

Sandra Cunningham has a rather cursory summary in The Atlantic, but her post’s comments section has some very interesting perspectives.