Notes:

What creates magnetic fields? (36.3)

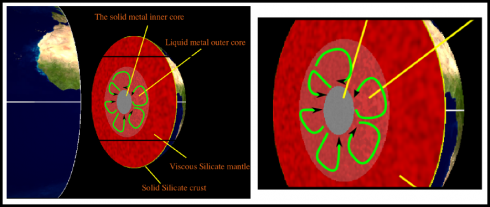

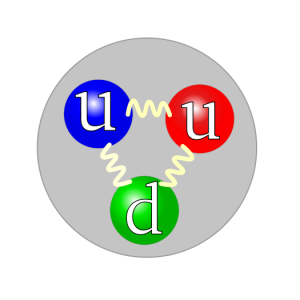

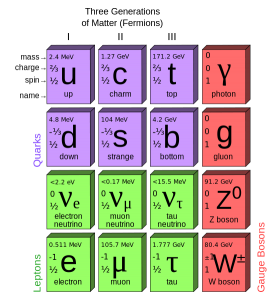

Magnetic fields are created by moving electric charges. At the atomic level:

- In atoms, most of the magnetic field comes from the spinning of electrons (remember electrons have a negative charge).

- In most elements, the magnetic fields of electrons pair up and cancel each other out

- Only certain elements, which have a few electrons that don’t pair up, can form magnets:

- Iron (Fe), Nickel (Ni) and Cobalt (Co) are the common magnetic elements.

- Iron is the most powerful magnetic element. It has 4 electrons whose magnetism are not canceled out (because of their arrangement in their electron shells)

- Some rare earth elements are also naturally magnetic.

Magnetic Domains (36.4)

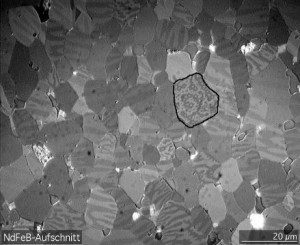

Each iron atom has a very small magnetic field, but when a bunch of them line up they add to each other to create a stronger field.

A region with a bunch of lined up atoms is called a magnetic domain.

If all the magnetic domains line up you have a strong magnet. If they’re all randomly arranged, you don’t have a magnet at all; they cancel each other out and it’s unmagnetized).

Magnetic Poles (36.1)

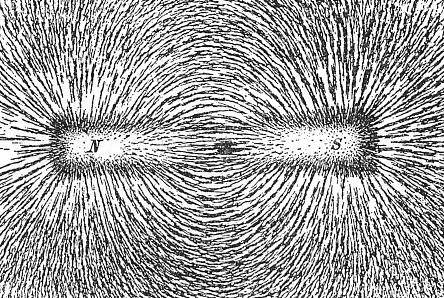

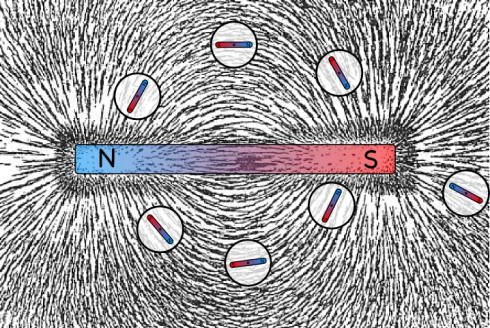

Magnets have two poles: a north-seeking pole, and a south seeking pole; they align with the Earth’s magnetic field.

Like poles repel and opposite poles attract.

The force between the poles depends on the strength of the poles (p) and the distance (d) between them:

Note how similar this equation is to the force between two charges (Coloumb’s Law; Fc), and the force between two masses (gravitational force; Fg).

Electric fields come from charged particles, which can be separated, but north and south magnetic poles belong to each domain (and even each atom) so they cannot be separated.

- If you break a bar magnet in half you don’t get a separate north and south poles, you just get two magnets, each with it’s own north and south pole.

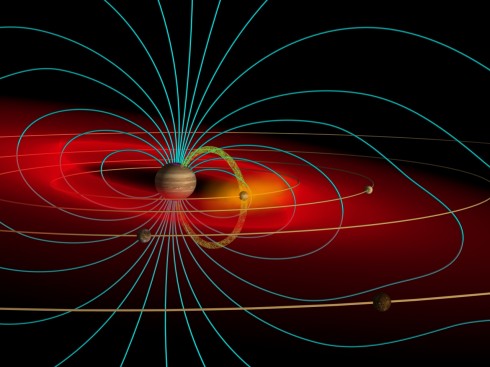

Magnetic Fields (36.2)

The region around the magnet that is affected by the magnetic force is filled with a magnetic field. In theory the magnetic force goes on forever, but is only strong in a relatively small region.

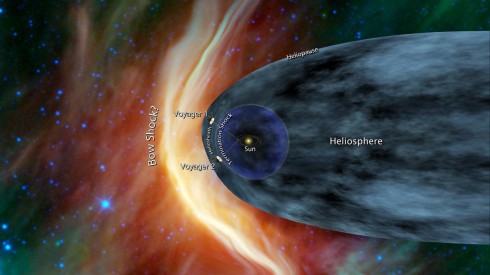

Compasses, which have magnets that are free to move, will align themselves with the magnetic fields around them. When you’re away from other magnets and electronic devices, compasses align with the Earth’s magnetic field.

So how do you create a magnet?

In an unmagnetized piece of iron, the magnetic domains are arranged randomly. If you place it in a strong magnetic field, the domains will align with the strong magnetic field and the iron will become magnetic.

- Softer iron alloys will align easier, and stay aligned to make strong, permanent magnets.

- Any metal with iron in it (like steel cans or filing cabinets) will gradually align their magnetic domains with the Earth’s magnetic field if they not moved for a long time, but the Earth’s field is not strong enough to make a permanent magnet.

- Stroking a piece of iron with a magnet will also align the domains.

- Touching a magnet to a paperclip or iron nail will align its magnetic domains and create a temporary magnet, which is why you can use a magnet to hold up a chain of nails. This induced magnetism will only last a short time and eventually (within seconds or minutes) of removing the magnet, the nails will lose their magnetism.

- Dropping or heating a permanent magnet will shift some of the domains out of alignment, reducing the strength of the magnet.