Catastrophic failure of one of our ovens! Last year when we started up the bread business, we bought two counter-top ovens within a couple of weeks of each other. They needed to be extra-large to fit two loaves of bread each, which made them a little hard to find. We got a EuroPro oven first, and when we found that it worked pretty well, we went back to try to get another. But just a week later, the store was out of stock and that type of oven could not be found in the city of Memphis or its environs.

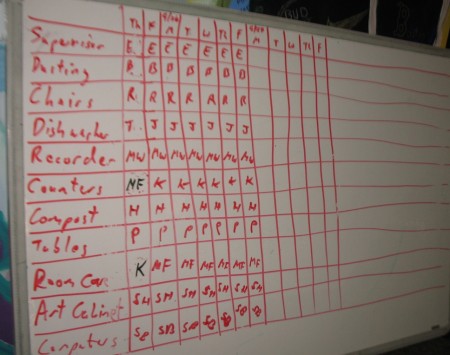

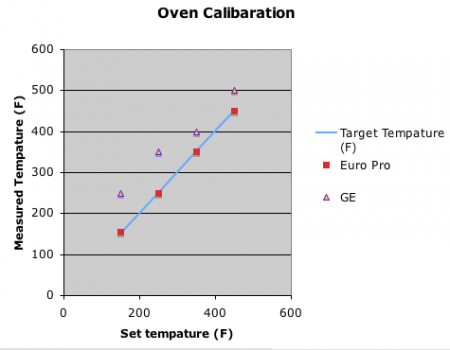

Instead we got a GE model. The price was about the same, as was the capacity. We quickly realized that the GE was quite the inferior product. The temperature in the oven was never the same as what was set on the dial. Our bread supervisor at the time ran a calibration experiment, the results of which you can see above, so we still managed to use the oven. Only this year, three weeks into the term, it conked out.

We sold at least one underdone loaf before we realized what had happened, and received a detailed letter in response (which our current bread supervisor handled wonderfully in his own well worded letter). Fortunately, we have found a newer version of our EuroPro oven, which seems to work quite well.

I like the oven calibration exercise. It was a nice application of the scientific process to solve an actual problem we had with the business. Though I know it’s not quite the same, I like the idea of doing annual oven calibrations just to check the health of our equipment and help students realize that the scientific process is a powerful way of looking at the world, not just something you do in science.