C.G.P Grey makes the case against the Electoral College in video form. He starts with how the Electoral College Works and continues with a well reasoned polemic against it: he’s big into democracy — one person, one vote.

Category: Social World

Should High Schoolers Be Able to Vote

Students in Lowell, Mass., are petitioning for the right to vote in their town. They argue that voting is an integral part of the civics they’re learning in high school, and they should be able to learn about, and vote on, issues in the communities where they grew up, and not have to wait until they’re in college.

Their campaign gained support of local politicians, cause the passage of a state law allowing the town to lower the voting age and even got a constitutional law professor (Lawrence Tribe) to write a letter supporting their case to the Massachusetts’ Secretary of State. They’re now organizing a ballot initiative for 2013.

A Modern Thermostat

There is a lot of potential for the new Nest thermostat to bring modern technology into some of the the essential but mundane devices that surround us. Its importance is not in the addition of new technology (which usually means new complexity), but in how that technology can actually make life easier, help save money, and reduce our impact on the environment by saving energy. Steven Levy has an excellent article in Wired about the project.

A key thing that students should note is the large range of expertise that went into creating this device: engineers, computer scientists, venture capitalists, and artistic designers to name a few. The ability to collaborate with diverse groups is an essential skill to master.

Just because of the large savings that can be gained, thermostats have been long overdue for an overhaul. Most buildings are heated by burning fossil fuels, like natural gas or coal, or with electricity that is produced by the burning of of fossil fuels. Similarly, cooling is also usually powered by electricity. Thus every savings in energy that results from this thermostat reduces the human impact on global warming. Because the energy savings means that you pay less for energy, saving the environment in this way means that you’re also saving money.

It’s good to see projects like this one come to fruition. We can only hope that they did a good job, that this is actually a good product, and that it is successful so similar projects will follow.

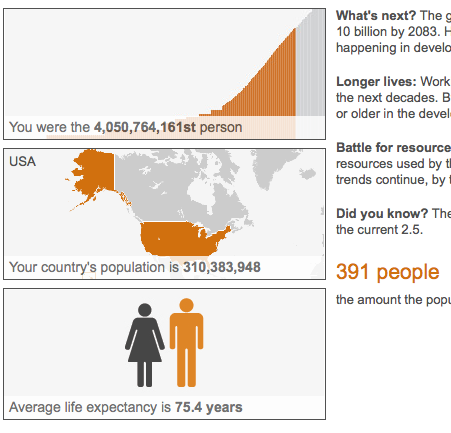

Your Place in the World (by Birth)

How many people were alive when you were born? How many people had lived before you were born? How many people were born while you were figuring this out?

The BBC’s The world at seven billion answers these questions.

(hat tip The Dish)

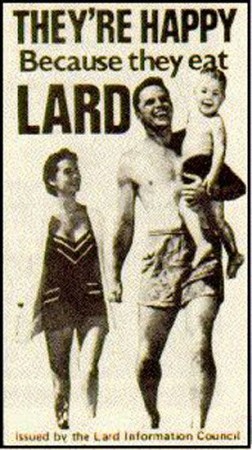

Facing the Advertising Noise

We face a lot of advertising. All the time. According to Martin Lindstrom, the author of Brandwashed, “the average American 3-year-old can recognize 100 brands” (NPR Staff, 2011). I usually discuss advertising at the same time as we’re talking about propaganda.

Guy Raz has an excellent interview with Lindstrom on All Things Considered.

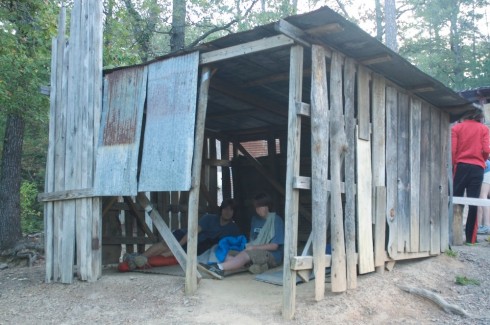

A Night in the Slums (simulated)

One of the highlights of the Heifer Ranch trip was the chance for students to spend a night in their global village. It’s really a set of villages, each simulating a life in an under-developed part of a different developing country.

The Guatemalan house is pretty nice; it keeps you out of the elements, you have actual beds, and running water. The Thai houses are actually pretty awesome. They stand on stilts next to the open fields, giving good air circulation and elegant views. They remind me a lot of some of the older houses from where I grew up. The refugee camp, on the other hand is pretty decrepit. The slums aren’t much better but at least have one house with a wooden floor, though the door was so broken it was pretty useless.

Our students were assigned villages at random, but varying numbers were placed in each village to replicate the population densities more accurately. One adult was assigned to each village. We were supposed to act as if we were incompetent (not hard I know), either as two-year-olds or senile elders.

I ended up in the high population slums.

On the positive side, I was not the only adult there. Mrs H., who had joined our group with her daughter for the week of activities at Heifer, was also assigned to the slums. On the negative side, she and the girls commandeered the one “posh” building that had an actual floor to sleep on. The boys and I had to sleep on the hard, stony ground.

It didn’t help that one of the boys was “pregnant”. One person in each group been given a water balloon in a sling and told to keep it with them, safe, until dinner, when they would “give birth”, at which point the others in the “family” could help take care of the “child”. A key objective was for the child to survive until morning.

The boys scouted all the houses in the village and scavenged a large piece of metal grating to sleep on. It was not great, but it was doable. Better, at least, than the concrete-hard, uneven ground.

There was a lot more that happened on that night. None of the groups was given enough to be comfortable on their own. There was a lot of haggling, trading and even commando raids, but, in the end, they pulled together and made something of it.

The experience was quite useful, I think. Conditions were uncomfortable enough to register with the students, though a single night is not enough to really internalize all the challenges of urban slums where over one billion people spend their lives. But it does provide some very useful context for the poignant images of Jonas Bendiksen (Living in the Slums) and James Mollison (Where Children Sleep).

Why Be Civil in an Argument?

Andrew Sullivan highlights Daveed Gartenstein-Ross’ explanation of why it’s so important to be civil in any argument.

I’ve come to see civility as important for a variety of reasons, but honestly, practical reasons loom rather large. First of all, it’s generally hard to win a name-calling contest. If I call someone an America-hating pinko, they can fire back that I’m a right-wing tool of the military industrial complex. Those two insults seem essentially to cancel each other out: why give someone an area that can end up a draw if I believe that I can prove all of my other arguments to be correct? Second, I find that if I’m civil, I can actually (sometimes) persuade people I’m arguing against that they’re wrong about an issue. In contrast, if I begin a debate by insulting someone, it only further entrenches him in his initial position, thus making it more difficult to talk sense into him. …

Being polite isn’t the same as being a pushover, nor is it the same as false collegiality that needlessly avoids confrontation. Indeed, I think that kind of fake collegiality should be avoided: the review I published this year of Robert Pape and James Feldman’s Cutting the Fuse is probably one of the harshest critiques a graduate student has produced of a work of that stature. But again, it eviscerates their argument without really personalizing the matter.

— Daveed Gartenstein-Ross (2011) in Special Abu Muqawama Q&A with Daveed Gartenstein-Ross

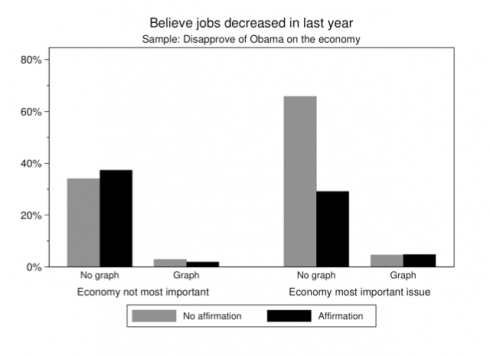

The Power of Graphs

A couple days ago I had students present their physics lab reports to the class. They did a good job, but I think I need to emphasize the importance of including graphs in their results. It’s much harder to look for trends and patterns in the data without charts, especially when presenting to an audience.

An interesting political science study (via Yglesias) found that it’s much easier to change people’s minds when you show them graphs, even when people don’t want to believe what you’re telling them.

[P]eople cling to false beliefs in part because giving them up would threaten their sense of self. Graphical corrections are … found to successfully reduce incorrect beliefs among potentially resistant subjects and to perform better than an equivalent textual correction.

–Nyhan and Reifler (2011): Opening the Political Mind? The effects of self-affirmation and graphical information on factual misperceptions

Teachers know how hard it can be to correct misconceptions – people tend to stick with the first thing they learned – so it’s good to see that graphical corrections can make a big difference.

Fortunately, my physics students are changing over to math next week, so we’ll be able to use their experimental data to draw lines, find gradients and do all sorts of interesting things.