Except that you can hear the dust and small rocks banging on your spacecraft.

from JPL.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

Except that you can hear the dust and small rocks banging on your spacecraft.

from JPL.

To the left, a long, narrow, lightly-wooded island. Skeletal trees, dying on the upwind end; drowned by the attrition of the waves. To the right, a narrow, eager, urban strip. Hotels and casinos, pressing against the water’s edge; vying for access to the white sand beaches and gentle waters of the sound. Such different places on either side, yet the one on the right is the reason we’ve come to the one on the left. We’re here as part of our Adventure Trip to pick up any artificial debris that’s managed to float across the sound and collect and contaminate the quiet, isolated beaches of the island.

We’d gotten on a pontoon at the research lab right after breakfast, so the early adolescents were still a little groggy. Our vessel’s captain asked a question about team mascots which promptly woke up approximately 63.64% of the class, and served as a topic of conversation for the twenty or so minutes it took to get to the drop-off point on the west-north-western end of Deer Island.

Mostly unobserved by my busy students were the half dozen shrimp boats casting their nets in the sound. Long, spider-like, almost robotic arms spread out from the vessel to lower the nets. It’s quite an impressive sight. Commercial shrimping is a major industry all along the Gulf coast.

Deer Island (and its hike). View Coastal Sciences Camp, Gulf Coast Research Lab in a larger map

The island itself is long and thin, wedge shaped, no more than a couple hundred meters at its widest at the eastern end, but thinning to less than 100 meters to the west. Although wider, almost all the trees seem to have died on the eastern end. Then there is a gap and the trees are mostly alive. Looking at the satellite image, you can see a clear channel cutting through the island. From the image, I’d guess the channel is tidal, with water moving back and forth, filling and draining the sound with each cycle of the tides. The sediment deposited in the quieter waters of the sound (to the north) seem to be forming a small, white-sand delta; the equivalent deposits on the south are probably washed away by the longshore current pretty quickly since that shore is exposed to the wind and waves.

Deer Island is not an active barrier island: twelve kilometers to the south, Horn and Ship Islands do that job today. However, given the shape of Deer Island, it may have once been a barrier when the coastline was further inland. This is all part of the coastal plains deltas, which includes the Mississippi Delta and smaller rivers. These rivers transport sediment from the mountains inland and deposit them in the ocean, gradually building out the land. As the deltas build out, the barrier islands also push out to accommodate them.

The pontoon pulled up on a broad, sandy beach then retreated to deeper waters where the fishing is better. The white sand beach we landed on was an artifice, just like the East Beach Drive beach we’d walked the day before. Our first steps betrayed the secret. Breaking through a thin cover of sand, we sank knee-deep into a rich black mud that’s the natural sediment in a quiet waterway like the sound.

Our guide, on the other hand, seemed to have a preternatural ability to avoid sinking into the mud, or even getting her feet wet, or even touching the water.

The first image was distorted using a four point distortion method with ImageMagick.

> convert sc-deer-island-1843.jpg -matte -virtual-pixel transparent -distort Perspective ‘0,0,0,200 0,664,0,564 1000,0,1000,0 1000,664,1000,664’ tst2.jpg

> convert sc-deer-island-1841.jpg -matte -virtual-pixel transparent -distort Perspective ‘0,0,0,0 0,664,0,664 1000,0,1000,200 1000,664,1000,564’ tst.jpg

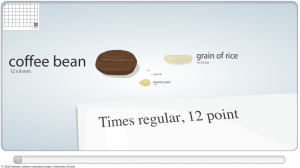

The Genetic Science Learning Center (which I’ve mentioned before) has a wonderful slider-bar animation that shows the differences in scale from what we perceive (a grain of rice or a coffee bean) down to the scale of cells, molecules and finally a carbon atom.

The smallest objects that the unaided human eye can see are about 0.1 mm long. That means that under the right conditions, you might be able to see an ameoba proteus, a human egg, and a paramecium without using magnification. …

Smaller cells are easily visible under a light microscope. It’s even possible to make out structures within the cell, such as the nucleus, mitochondria and chloroplasts. [my example] … The most powerful light microscopes can resolve bacteria but not viruses.

To see anything smaller than 500 nm, you will need an electron microscope. … The most powerful electron microscopes can resolve molecules and even individual atoms.

–Genetic Science Learning Center (2011, January 24) Cell Size and Scale. Learn.Genetics. Retrieved June 13, 2011, from http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/begin/cells/scale/

Some people knit bacteria, our students create models of plant and animal cells as an assignment, and Luke Jerram blows viruses in glass.

Interestingly, he does not use colors, just clear, transparent glass, because while almost all pictures you see of viruses, from scanning electron microscopic images to text-book diagrams, have color, the color is added for scientific visualization. So, he believes, his glass replicas are more realistic. This is described in this interview.

About the works:

The pieces, each about 1,000,000 times the size of the actual pathogen, were designed with help from virologists from the University of Bristol using a combination of scientific photographs and models.

— Caridad (2011): Harmful Viruses Made of Beautiful Glass

The video below shows how it’s done.

There is a lot more information on the art and the science at the Glass Microbiology website.

The National Academy Press has just made all of its publications free for downloading (as pdf’s). Of particular interest is the Education section which includes titles such as:

There are 20 books in the Education section, and while many of the books in the other sections are quite technical, there are some gems among the 4,000 available titles.

The … organic materials in [some] meteorites probably originally formed in the interstellar medium and/or the solar protoplanetary disk, but was subsequently modified in the meteorites’ asteroidal parent bodies. … At least some molecules of prebiotic importance formed during the alteration.

Herd et al., 2011: Origin and Evolution of Prebiotic Organic Matter As Inferred from the Tagish Lake Meteorite

Amino acids are the building blocks of life as we know it. They can be formed from abiotic (non-biological) chemical reactions (in a jar with electricity for example). It’s been known for a while that amino acids can be found on comets and asteroids, but now this fascinating article suggests that a lot of the chemical reactions that created these precursors to life happened on the asteroids themselves. Then when the asteroids bombarded the Earth, the seeds of life were delivered. More details here.

This, of course, is just one of several hypotheses about the origin of life on Earth: livescience.com outlines seven.

This video from NASA (via physorg.com) includes a nice little section showing the movement of charged particles (cosmic rays) through the Sun’s magnetic field. What’s really neat, is that the Voyager spacecraft (now 33 years old) have discovered magnetic bubbles at the edge of the solar system that make the particles dance a little. It’s a wonderful application of the basic principles of electricity and magnetism.