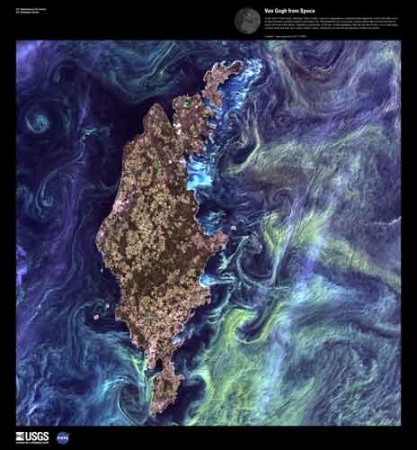

For the geography nerds, but perhaps also for those with an appreciation of the natural beauty of the world. The US Geological Survey has a series of satellite pictures chosen just for their sheer beauty.

The Landsat satellites that take these pictures usually photograph in more than just the human-visible color spectrum. For many geologic and environmental purposes, different infra-red wavelengths are often better for seeing details on the Earth’s surface. The USGS has a nice primer on the Landsat program. Many of the color images posted here were reconstructed from different color bands.

The resulting images can be exceptionally beautiful and somewhat surreal. I like that there is an abstract surface beauty, divorced from the content, meaning and understanding that a closer analysis of the images yields to the eye of the trained observer: delicate swirls of algae might be signs of eutrophication to a biologist; dendritic deltas tell the geologist about sediment load, offshore currents and mass balance.