If we can use music videos as a shorter proxy for introducing literature responses, then what about other types of media. On The Media had an interesting interview with the Tom Bissell, the author of “Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter“. Bissell argues that there is art worthy of criticism in video games, but there is not nearly as much as there should be.

I tend to like violent games, the same reason that I’ve worked as a war correspondent, the same reason I wrote a book about a war. I’m interested in violence.

That said, there are some games that have interesting stuff to say about violence and some games that just treat it mindlessly. And, you know both can be fun. But the ones that really affect me are the ones that actually try to address the subject. – Tom Bissell on On The Media.

In particular, he highlights “Far Cry 2”:

There’s a game called Far Cry 2 that takes place in a contemporary African civil war. It’s extremely beautiful.

And yet, it is just the most unrelentingly savage game I think I’ve ever played.

Most games that are violent give you the gun, push you in the direction of the bad guys and say hey, go kill all those guys, they’re bad. You’ll be rewarded. Good job.

Far Cry 2 does something really confounding. Going through the game, quote, “getting better at killing,” the game kind of introduces slowly that you’re actually not helping things, that, in fact, you’re kind of the problem.

Everything you’re doing is just making this conflict worse. So by the end of the game you’re just a wreck. You’re progressing through the game because that’s what the game’s asked you to do, but it’s also throwing all of this stuff back at you that’s actually shaming you a little bit for being participant in this virtual slaughter. And I love that about it. – Tom Bissell on On The Media.

Is he reading too much into violent video games trying to justify his own habits? Perhaps, but he does have a point.

When my students were telling me about Call Of Duty:Modern Warfare 2, one of the first things we talked about was the infamous airport mission. The player is an undercover agent with a terrorist organization and has to participate in shooting civilians in an attack on an airport. Jesse Stern, the scriptwriter for the video game says the mission was intended to be provocative:

People want to know. As terrifying as it is, you want to know. And there’s a part of you that wants to know what it’s like to be there because this is a human experience. These are human beings who perpetrate these acts, so you don’t really want to turn a blind eye to it. You want to take it apart and figure out how that happened and what, if anything, can be done to prevent it. Ultimately, our intention was to put you as close as possible to atrocity. As for the effect it has on you, that’s not for us to determine. Hopefully, it does have an emotional impact and it seems to have riled up a lot of people in interesting ways. Some of them good. Some of them bad.

– Jesse Stern in Gaudiosi, 2009.

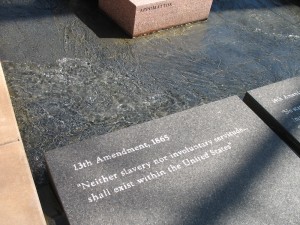

There is a difference between vicariously becoming a participant in violence when a novelist lets us see the world through the eyes of a killer, and actually having to pull the virtual trigger yourself, but it seems as much one of degree as anything else. While I’ve seen some initial evidence that violent video games are bad, I’m not familiar at all with the evidence that violent novels are also bad.

Perhaps, however, when we start treating video games, particularly violent ones, in as pedantic a way as literature is sometimes treated, maybe they’ll lose some of their appeal. Or maybe, they’ll just become more educational experiences. Stern again:

When we tested the level, it was interesting. …people would get angry or sad or disgusted and immediately wonder what the Hell was going on here. And then after a few moments of having that experience, they would remember that they were in a video game and they would let go. Every single person in testing opened fire on the crowd, which is human nature. It feels so real but at the same time it’s a video game and the response to it has been fascinating. I never really knew you could elicit such a deep feeling from a video game, but it has.