Brandon Scott Gorrell has produced a wonderful salvo for our never-ending efforts to promote rational discussion.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

Brandon Scott Gorrell has produced a wonderful salvo for our never-ending efforts to promote rational discussion.

As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1.

— Mike Godwin, 1989.

Our daily discussions of The Chrysalids have gone on long enough that Hitler came up. I can’t remember the details, but somehow, it occurred to one of my students that, since we don’t know exactly when the story is set, and given the outstanding question, “Did they ever find Hitler’s body?” what if Hitler turned up in the book.

Sigh.

Quite coincidentally, I ran into this article today, about Hitler’s last bodyguard. Apparently, he’s getting too old to answer all his fan mail. Tennessee gets a mention.

Sigh.

On a final note, the above quote about Godwin’s Law is a nice one to use in a cycle where we’re talking about probability.

Cheers.

No, not the three musketeers. These are the three things you need to persuade people: credibility, emotion and logic (Aristotle in On Rhetoric). EV, in a comment on my post on Critical Reading, pointed out an article called Classical Rhetoric, on the wonderfully named website, The Art of Manliness.

I’m trying to work this information into a lesson on Rhetoric, which, because of how closely they relate to adolescent development, the emergence of abstract thinking, and how we establish our place in the world, I’m hoping to stick into the Personal World curriculum.

To start with, here are my notes on Ethos:

Credibility, the quality of being believable, depends on two things: the trustworthiness of the person, and their demonstrated knowledge of the issue at hand.

We believe good men more fully and more readily than others. … his character may almost be called the most effective means of persuasion he possesses. – Aristotle

Credibility and strength of character count, even in the simplest of things. The answer to the question, “Did you take the last cookie?” will only be believed if the questioner trusts the person being asked to answer honestly.

Adolescents, who tend to be idealistic and opportunistic, need to pay close attention to the idea that history and reputation matter. They sometimes tend to view each individual encounter as it’s own separate event, unaffected by all the previous encounters and similar events. It is essential to recognize that this is not the case.

Credibility is most important because, although the cookie is a small thing, if you say, “No,” while the answer should be, “Yes,” then when the big questions come up, no matter how logical your arguments, you have no basis on which to persuade. Trust and character are hard to build, but easy to destroy.

This guide, from a longtime commenter on Megan McArdle’s blog, does an excellent, if cynical, job of explaining how to win an online argument. It includes:

Most of these techniques are appeals to the emotions (pathos). They can, and may sometimes need to, be used to support a good, well reasoned, argument (logos).

[B]efore some audiences not even the possession of the exactest knowledge will make it easy for what we say to produce conviction. – Aristotle in On Rhetoric

Be careful how you use these things, and watch out for them, because they don’t only occur online, you’ll see them often in any conversation.

With the exception of informed ones, opinions have little use as supporting evidence. – Critically Evaluating the Logic and Validity of Information from Cuesta College.

Cuesta College has a nice but fairly dense webpage on, “Critically Evaluating the Logic and Validity of Information“.

It starts with distinguishing between facts and opinions, goes into evaluating arguments and rounds up with asking critical questions. There’s lots of good information, but it needs to be parsed, broken apart, and condensed for middle school students.

Facts are statements that can be verified or proven to be true or false. Factual statements from reliable sources can be accepted and used in drawing conclusions, building arguments, and supporting ideas.

Opinions are statements that express feelings, attitudes, or beliefs and are neither true nor false. Opinions must be considered as one person’s point of view that you are free to accept or reject. With the exception of informed ones, opinions have little use as supporting evidence, but they are useful in shaping and evaluating your own thinking. [My emphasis]

– Critically Evaluating the Logic and Validity of Information from Cuesta College.

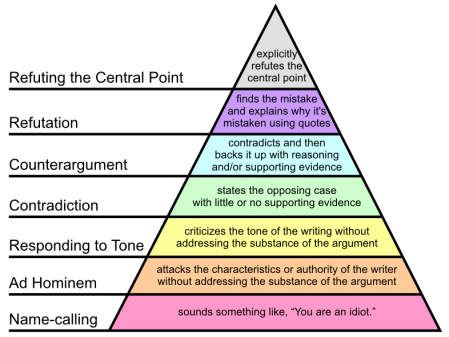

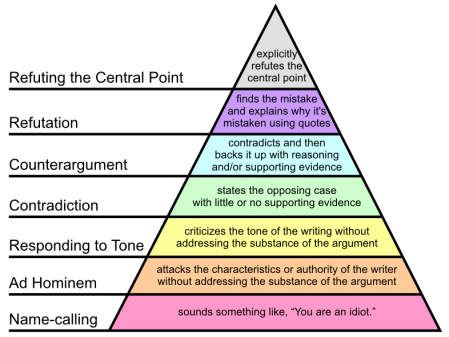

This can be tied in with my previous notes on Paul Graham’s Hierarchy of Disagreement to create a set of lessons on critical thinking and evaluation.

Faced with the rapidity at which anonymous conversations on the internet deteriorate, Paul Graham’s broken things down into six levels of argument. It starts with name-calling at the bottom and ends with the Refutation of the Central Point at the top.

This is a wonderful model. I especially like the diagram because it’s really easy to pick out which level your argument is on. I’m going to make a poster sized version of this and post it on the wall. And, there’ll be a lesson.