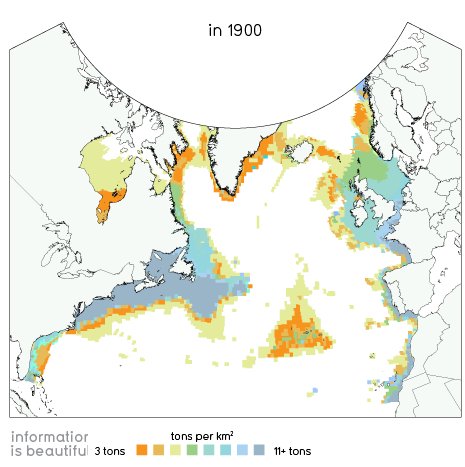

In 1900 fish stocks in the North Atlantic looked like this:

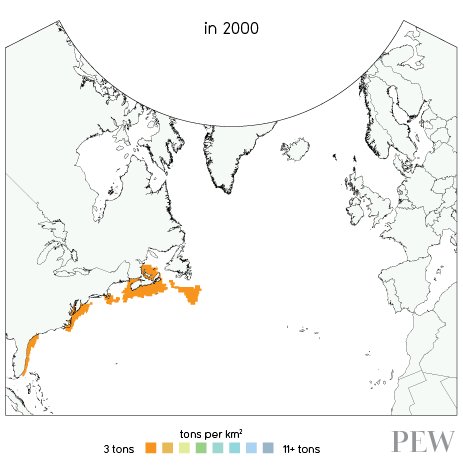

IN the year 2000, fish stocks looked like this:

There are more data and visualizations on the European Ocean2012.eu site.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

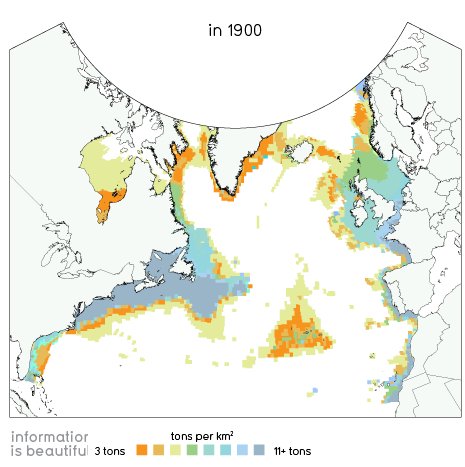

In 1900 fish stocks in the North Atlantic looked like this:

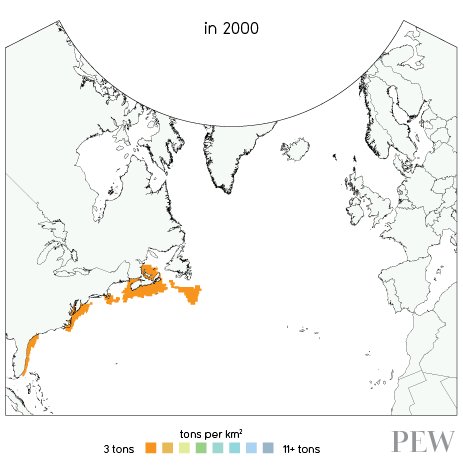

IN the year 2000, fish stocks looked like this:

There are more data and visualizations on the European Ocean2012.eu site.

If learning is not for its own sake, it isn’t liberal learning. It’s a utilitarian calculus for material self-advancement. The important things are not worth knowing because they are useful. They are worth knowing because they are true. [my italics]

–Andrew Sullivan (2011): Education For Its Own Sake

This quote, feeds off a plea by Freddie DeBoer against our constantly putting things in terms of dollars, cents and economic value. It argues against much of the premise of behavioral economics (and much of environmental economics too), which tries to better understand human nature by translating everything into money.

The economists themselves will tell you that this remains just one part of the story, and the work brings us to a better understanding of how humans behave and what they really value, but, living in a very capitalist society, it’s easy to lose track.

One of the key advantages of free market economies over strict socialist ones, is the much greater incentive to innovate. NPR has a wonderful case study in free enterprise in this article on the use of new water-filled tubes instead of sandbags to prevent flooding.

NPR’s interview the inventor of the AquaDam and talk about how he came up with the idea (playing with water balloons), how the water-filled dykes work, who are using them, and how much they costs.

The only things that were a little difficult to understand, was the description of the tubes themselves, and the explanation of why they don’t move. The idea is pretty simple, but an image helps.

Note: Minnesota Public Radio also has a good article with pictures.

I used my notes and the Keynes versus Hayek music video as part of our reading this week. As usual, half the class tried skipping directly to the video, but it became pretty clear, as I suspected it would, that they didn’t understand what was going on if they had not read the notes.

We’ll be discussing the video tomorrow when we try to wrap up the week’s work, but, as one student mentioned, it can be a little hard to figure out the words in the rap. Fortunately, the Econ Stories website has been updated to include the lyrics.

Even without the lyrics, however, I really like that you can get a good idea about the competing economic theories solely from the video itself, since it’s just a very detailed extended metaphor. It’s so chock full of symbols that it could probably be used to supplement the Calvin and Hobbes comic strip in our language lessons on finding symbols in texts.

To get students a little more familiar with personal finance, we’re doing a little bank account simulation, and I created a little Excel program to make things a little easier.

It’s really created for the class where students can come up to the bank individually, and the banker/teacher can enter their name and print out their checks as they open their account.

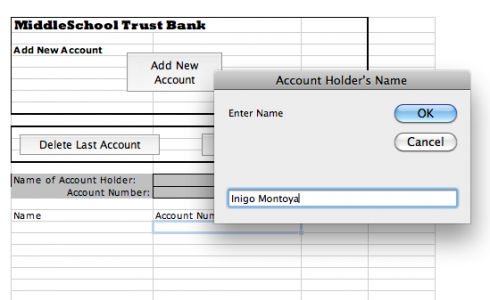

The front sheet of the spreadsheet (called the “Bank Account” sheet) has three buttons. The first, the “Add New Account” button, asks you to enter the student’s name and it assigns the student an account number, which is used on all the checks and deposit slips. The other two buttons let you delete the last account you entered, and reset the entire spreadsheet, respectively.

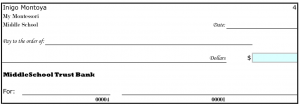

Once you’ve created an account the spreadsheet updates the “Checks and Deposit Slips” sheet with the student’s name and account number. If you flip to that sheet you can print out eight checks and five deposit slips, which should be enough to get you through the simulation. The checks are numbered and have the student’s account number on them.

There are two other sheets. One is the “Checkbook Register”, which is generic and each student should get one, and the other is called “Customer Balances”. The latter is set up so you (the teacher) can enter all the deposits and withdrawals the students make, and keep track of it all on the same page.

Yes, it’s a bit of overkill, but I though that, since I was going through the effort, I should probably do a reasonable job. Besides, it gave me a chance to do a little Visual Basic programming to keep my hand in. While I teach programming using VPython (see this for example, but I’ll have to do a post about that sometime) you can do some very interesting things in Excel.

Note: I’ve updated the Excel file.

Adam Smith (1776) described how each individual, working solely for their own self-interest can interact, in a fair marketplace, to maximize the benefits for everyone. The unintentional, “invisible hand” of the market converts selfish actions toward a greater good if the conditions are right. The key condition is the rule of law.

Without clear, enforced laws, to prevent theft and to ensure property rights, the free-market economic system breaks down. Of necessity, the laws must be fair. If they are not then they will be violated, and in general it helps to minimize the number of laws people have to keep track of. People are free to do whatever they want, as long as they follow the law.

Similarly the classroom. Students need clear rules. Rules that establish the proper way to interact with their peers, and rules that protect individual rights to property and autonomy. While we hope they subscribe to their natural altruism, and indeed encourage its development, there need to be clear laws that they all can agree on. This is why we spend a lot of time at the start of each year be developing our set of rules and classroom constitution. To gain the maximum legitimacy, students develop the rules themselves, with some guidance, and establish ways of enforcing them. In my classroom, for example, we also dedicate time twice a week for a sort of legislative/judicial session, designed to deal with issues and problems that crop up.

But the reason for setting these limits is to allow freedom: freedom to learn.

If economics ultimately boils down to the study of human behavior, and our students are ultimately human (stick with me for a second here), then economic theory ought to be able to inform the way we teach. In fact, I’d argue that constructivist approaches to education, like Montessori, work for the same reasons that free-markets outperform highly-centralized command economies: freedom (within limits) better maximizes human welfare. I think this applies both to students in aggregate (the entire student population), and to the individual student also, though you probably have to aggregate over time.

As a study of human behavior economics differs from psychology, sociology and the other social sciences primarily because it uses money as a metric. This gives it a lot more data to play with. The last century has clearly demonstrated the advantages of the “invisible hand” of the free-market over highly-centralized command economies in providing for the broader public good. So what lessons from the study of economics can we apply to education?

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that we should be treating our schools and classrooms as businesses. We’re not trying to maximize profits for a firm (via test scores or however else that might translate to education), we’re trying to maximize the welfare of our students, which I take to mean, helping them achieve their full potential.

As we’ve seen in our studies of economics, flexible, market-based approaches are much better (more efficient) at achieving goals that the command-and-control, dictatorial model. The evolution of EPA’s approach to regulating pollution is an excellent example of how a federal agency learned to employ the experience of economics to better achieve a public good.

In the 1960’s and 70’s, rivers catching on fire, smog, and books on the invisible consequences of pollution, like Silent Spring, inspired the environmental movement and spurred the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The EPA’s job was, and is, to enforce the laws that reduce pollution and protect environment. In the beginning, they did this by telling industry and companies what to do: the EPA mandated strict limits on the emissions from factories; and power plants were required to install the “best available technology” to reduce pollution. These approaches sound good, and are certainly necessary for pollutants that are dangerous to places close to where they are emitted, but they can be expensive, encouraging people to look for loopholes in the rules so they also become expensive to enforce.

You get the same problems with long, detailed lists of rules in the classroom. Students try to circumvent the letter of the law, rather than adhere to the spirit of the rules. “No iPods allowed,” is forced to evolve into “No Personal Electronic Devices.” Then come the questions, “What about watches?” and, “What about iPads?” so more rules need to be added to the list. By the end of the week you’re approaching a list of rules approaching the length of the tax code, and still adding more.

In the case of environmental regulation, to deal with this type of problem, the field of environmental economics emerged. Environmental economists try to figure out how to achieve the pollution reducing outcomes that everyone wants in the most economically efficient way possible. More efficiency means lower costs to society. They found that there are usually quite a number of ways to achieve the environmental objectives, using the principles of the free market, that are much more efficient than the command-and-control approach the EPA had been using.

Economists like to use mathematics. There are lots of supply and demand curves, and lots of derivatives, which tend to force some over-simplification (in much the same way that your textbook supply and demand curves are almost invariably straight lines). However, sometimes simple models can lead to a better understanding of how people in societies work.

In the 1980’s coal burning factories and power plants were churning out a lot of pollutants. One of these, sulphur dioxide (SO2) would react with rainwater and to create sulphuric acid, which would fall as acid rain. Acid rain was a huge problem because lots of plants and animals living in lakes, streams and forests were finding it hard to adapt to the increasing acidity of their environment. Furthermore, more acidic rainwater was damaging the paint on people’s cars and dissolving limestone statues and buildings.

So the EPA implemented a Cap and Trade program. They had a good idea of how much SO2 was being released into the atmosphere, and they know how much they wanted to reduce it by, so they started to issue companies permits to pollute.

The trick was that EPA would only give out permits equal to the total amount of SO2 emissions they wanted, and every year they would reduce the amount of permits until they reduced the pollution enough to resolve the acid rain problem.

Now all the companies that polluted SO2 had to either buy a permit or stop polluting. If they could easily reduce their pollution, a company might have extra permits that they could sell to a company that was having a harder time. In theory, some companies could even buy up permits from other companies and increase their pollution. But since the EPA was only giving out so many permits, whatever happened the total SO2 pollution was still going down.

Doing it this way let the EPA set the goals and let the market for pollution permits allocate how the actual pollution reduction got done. Since the permits could be sold, this encouraged the companies that could easiest reduce their pollution to do so, resulting in a reduction in pollution at the lowest cost.

It also meant that companies were now starting to pay for the environmental damage they were doing. Acid rain is a regional problem so it’s hard to say that your pollution from your factory in Ohio is specifically causing the acid rain here in my forest in Vermont. The atmosphere was being treated as a common dumping ground.

Cap and trade is not without its problems, however, at least in this case, it worked extremely well.

Montessori believed that children have an innate desire to learn. We’ve seen how easily praise and rewards can damage that internal drive. I have, however, found it hard to identify my student’s innate desire to do the dishes. They may want a clean environment, they may have been trained since pre-kindergarten to clean up after themselves (restore their environment), but their is quite often a reluctance to doing it themselves.

The relationship to the pollution issue is startling to think about at first, but really the issues are the same. After struggling for quite a while to get everyone to do their classroom jobs, recognition of the parallel between my job and the EPA’s lead me to thinking about creating the Job Market Trading Board. Students can trade jobs and when they do it, but in the end, the jobs get done. I remain impressed at how well it has worked.

The basic principle is more general though: set the goals and let the students figure out the best way to accomplish them.

After going through the free-market part of the economic system simulation, the least wealthy people –the students who ended up with the least kilobucks— staged a socialist revolution.

Well the most wealthy students were not too happy with that, because the revolutionaries confiscated all their wealth, assigned them all jobs (to simulate a command socialist economy), and started paying everyone equally. One student, assigned to produce food, produced a chicken, a cookie, and a dead socialist. She got sent to jail.

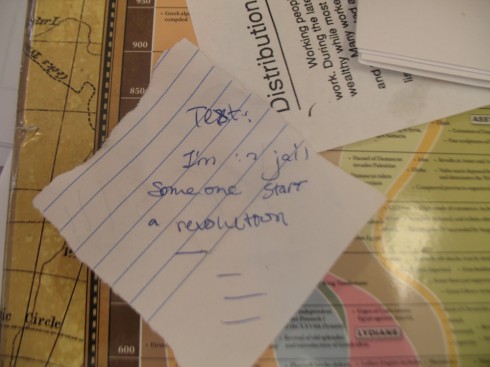

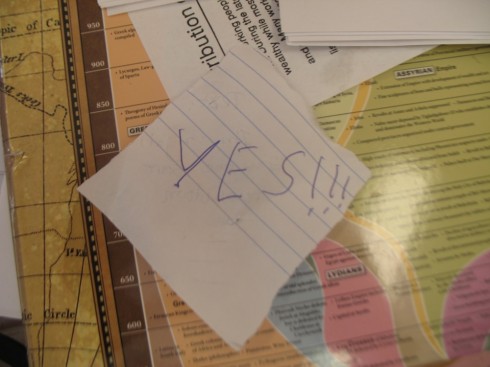

Fortunately, for her at least, she was able to get hold of a phone that had been left lying around from the market part of the simulation, so she sent a simulated text to her fellow former oligarch to try to start the counter revolution. She got a return text:

It’s nice to see that our time spent talking about Egypt has not been wasted.