If I present information to you orally, you’ll probably only remember about 10% 72 hours after exposure, but if I add a picture, recall soars to 65%.

–Alex Lundry (2009): Chart Wars: The Political Power of Data Visualization

How you present visual information is important. And my students are discovering this as they work up their Independent Research Projects (IRP’s) this week.

In the spring they are fairly free to pick their topic and style of IRP. Some choose research projects, others term papers, and a few do things that strike their fancy, like writing fiction or programming games.

In the end, they submit a written report and give a presentation.

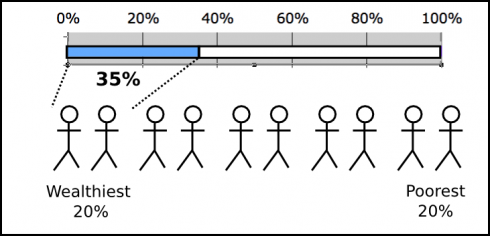

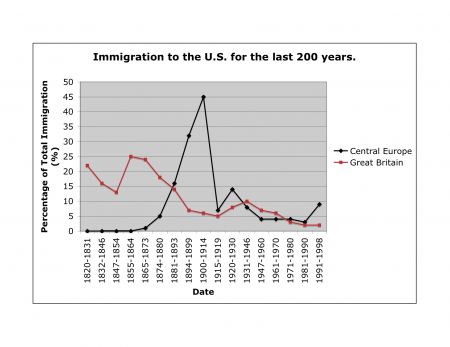

For research projects, I have one student who did a great job of coming up with a hypothesis and testing it. He even compiled a nice table of his data for his results section, but was reluctant to go through the effort of making a graph. After all, he claimed, anyone reading his report (or watching his PowerPoint presentation) could just look at the table and read the data off there themselves.

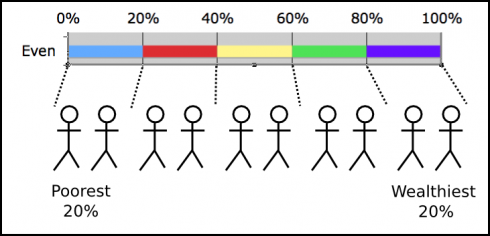

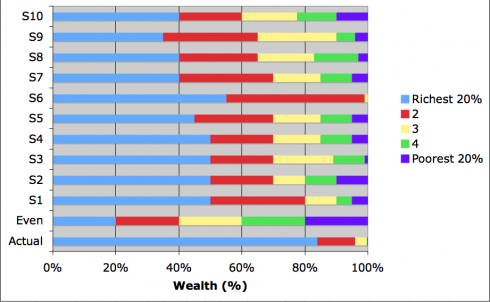

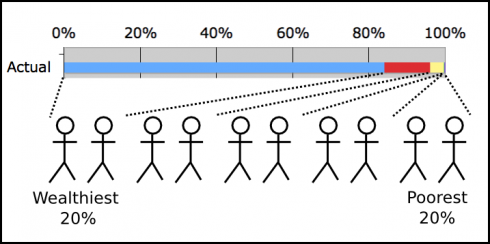

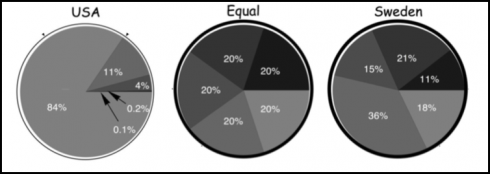

My response was that people absorb the data much more effectively when it’s presented graphically. Fortunately, Alex Lundry has a nice little presentation that reinforces this point. It also gives a few tips about what to look out for in graphics, because they can be used to mislead.

The key quote (via The Dish) is this:

Vision is our most dominant sense. It takes up 50% of our brain’s resources. And despite the visual nature of text, pictures are actually a superior and more efficient delivery mechanism for information. In neurology, this is called the ‘pictorial superiority effect’ […] If I present information to you orally, you’ll probably only remember about 10% 72 hours after exposure, but if I add a picture, recall soars to 65%. So we are hard-wired to find visualization more compelling than a spreadsheet, a speech of a memo.

–Alex Lundry (2009): Chart Wars: The Political Power of Data Visualization

Here’s Lundry’s five minute presentation.