Last Friday, we were lucky enough to have a horticulturalist, Scott Woodbury, visit the Environmental Science class. Scott teaches the Native Plant School at the Shaw Nature Reserve, and spends a lot of effort dealing with invasive species.

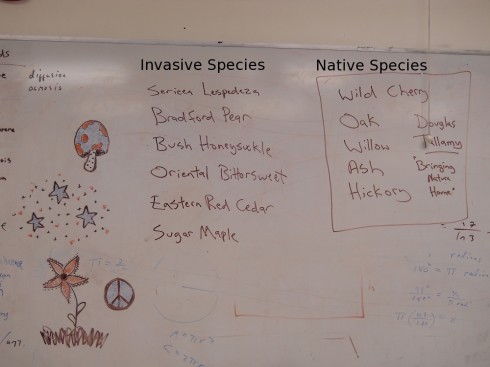

The extent of the problem on our campus was quite sobering. The invasive trees, shrubs, and vines displace native plants, and animals as well because the native fauna are not adapted to them. A native elm might support somewhere around 300 species of caterpillar, while an imported bradford pear might have just a few; Douglas Tallamy has a good book, Bringing Nature Home, on the subject.

The bradford pears are quite pernicious. They were once favored by landscapers because of their beautiful spring flowers and brilliant fall colors. However, the birds spread their seeds far and wide, and now bradford pear saplings can be found all over the campus. They tend to do better in the grassy areas at the sides of the roads, as well as on the slope overlooking the school that’s still in the early stages of succession. The saplings can be cut down with hand saws, and I doubt anyone would notice that they were gone, but it’s probably going to be tricky getting permission to take down the half dozen mature trees on the front lawn that were planted when the school was built.

The dark secret about the oriental bittersweet vine that’s attacking the trees along the creek, is that they probably came from the Shaw Nature Reserve. Apparently there was a mistake at one of their sales, and one of our teachers bought the wrong species of bittersweet. Cutting the vines that are growing up the tree trunks should slow them down.

Sericea lespedeza has pretty much taken over the slope above the school. This herb was imported for erosion control but was found to be extremely hard to control. On the plus side, while it does well in disturbed areas like the slope, since it is an early succession species, it will be succeeded by the tree species that are now growing up through it. It’s just going to take a number of years.

At least the bush honeysuckles, which can be found all along the creek, can be hand pulled if they’re small enough. However, we’ve got some pretty big specimens that are much harder to get rid of. They grow fast, leaf-out early, and crowd out the native shrubs.

Interestingly, all these four species are all from Asia. The latitude is similar to Missouri’s so species from that part of the world can thrive here where the climate is similar and they don’t have their native predators and pests. Scott did point out a couple of native species — eastern red cedars and sugar maples — that have become much more aggressive because of all the fire suppression over the last few hundred years, but that’s a story for another time.