My students just presented their Individual Research Projects (IRPs) to their peers and their parents, and, I have to say, they did quite a good job.

They’re called IRPs, but while they are independent projects, they actually don’t all have to be research. This year we had a number of research papers, a few experiments, a short story, and computer program. The last two were by graduating eight graders, who I like to encourage to do something different that aligns with their interests: one wants to be a writer, while the other is really interested in programming.

Now you’re thinking, “That family is mean!” You could say that, but that’s not why we do it.

– From “Beverly” by P.Z.

It helped that it was a friendly audience who’d just been fed (food always helps), but it was nice to see how confident they were, and, as one parent remarked to me, how much progress they make from year to year. Even my shyest student had everyone laughing with her short story.

Even better still, was the fact that although I did not have the time to review all the presentations in great detail (students have to write a report first, which tends to be the focus of my reviews), the peer-review process, and the experience they’ve had doing presentations all year, really paid off.

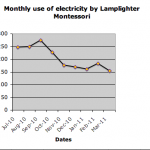

And on average, an increase of .100 OPS adds 2 million to the player’s salary. So players on steroids on average get $12,512,630 more throughout their career.

-Michael F. in ” ‘roids”

Tomorrow is graduation, which I always find to be anticlimactic; after all, it’s the work that important and interesting, not so much the diploma at the end. These excellent presentations however, were a great way to cap off the year.