xkcd has published an excellent graph showing where different dosages of radiation come from and how they affect health. It’s a complex figure, but it’s worth taking the time to look through. I find it easiest to interpret going backward from the bottom right corner that show the dosages that are clearly fatal.

One red square of 100 red blocks is equal to one seivert, which is the radiation dosage that will kill you if you receive it all at once. Note:

- If you were next to the reactor core during the Chernobyl nuclear accident, you would have gotten blasted by 50 Sv.

- 8 Sv will kill you, even with treatment.

- Getting 0.1 Sv over a year is clearly linked to cancer.

- One hour on the grounds of the Chernobyl nuclear plant (in 2010) would give you 0.006 Sv.

- Your normal, yearly dose is about 0.004 Sv, just about how much was measured over a day at two sites near Fukushima.

- Eating a banana will give you 0.000001 Sv.

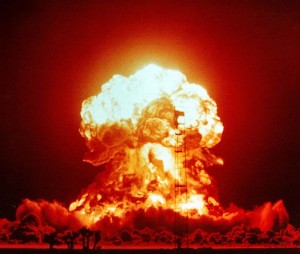

While I did not find equivalent exposure levels, the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki lead to many deaths and sickness from radiation created by the explosions. Within four months, there were 140,000 fatalities in Hiroshima, and 70,000 in Nagasaki (Nave, 2010). The Manhattan Engineer District, 1946 report describes the radiation effects over the first month:

The effects were not limited to the explosion itself, though. There is one estimate, that 260,000 people were indirectly affected:

Radiation dose in a zone 2 kilometers from the hypocenter of the atomic bomb was the largest. Also, those who entered the city of Hiroshima or Nagasaki soon after the atomic bomb detonation and people in the black rain areas were exposed to radiation. … some people were exposed to radiation from black rain containing nuclear fission products (“ashes of death”), and others to radiation induced by neutrons absorbed by the soil upon entering these cities soon after the atomic bomb detonation.

— Hiroshima International Council for Health Care for the Radiation Exposed (HICARE): Global Radiation Exposures.

HICARE also has a good summary of what happened at Chernobyl, where 31 people died at the time of the accident, about 400,000 were evacuated, and anywhere between 1.6 and 9 million people were exposed to radiation. Modern pictures of the desolation of Chernobyl are here. The Wikipedia article has before and after pictures of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.