Emily Hanford has an excellent article on NPR about college professors who are transitioning away from lectures as a teaching method. They’re now focusing more on peer-teaching.

Tag: peer teaching

Finnish Schools and Montessori Education

The BBC has a fascinating article on the Finnish educational system; specifically, why it consistently ranks among the best in the world despite the lack of standardized testing. A couple things stand out to me as a Montessori educator.

The first is the use of peer-teaching. There’s a broad mix of abilities in each class, and more talented students in a particular subject area help teach the ones having more difficulty. It’s something I’ve found to be powerful tool. The advanced students improve their own learning by having to teach — it’s axiomatic that you never learn anything really well until you have to teach it to someone else. The struggling students benefit, in turn, from the opportunity to get explanations from peers using a much more familiar figurative language than a teacher, which can make a great difference. I give what I think are great math lessons and individual instruction, but when students have trouble they go first to one of their peers who has a reputation for excelling at math. In addition to the aforementioned advantages, this also frees me up to work on other things.

A second thing that stands out from the BBC article is how the immense flexibility the teachers have in designing their teaching around the basic curriculum coincides with a very progressive curriculum. This seems an intimate consequence of the lack of assessment tests; teachers don’t have to focus on teaching to the test and don’t face the same moral dilemmas. Also, this allows teachers to apply their individual strengths much more in the classroom, making them more interested and excited about what they’re teaching.

E.D. Kain has an excellent post on the video The Finland Phenomenon that deals with the issue specifically. It’s full of frustration at the false choices offered by the test-driven U.S. system.

(links via The Dish)

The scientific explanation of why adolescents know everything!

The central proposition in our argument is that incompetent individuals lack the metacognitive skills that enable them to tell how poorly they are performing, and as a result, they come to hold inflated views of their performance and ability…. the way to make incompetent individuals realize their own incompetence is to make them competent.

– Kruger and Dunning (1999): Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments (pdf)

If you don’t know what you’re doing, then it’s quite likely that you don’t know that you don’t know. Kruger and Dunning (1999) did a set of interesting studies to show this to be the case. It explains why people with the least information and knowledge about a subject may feel the most confident to opine about it.

It kind of explains why adolescents know everything. I know that I knew everything when I was 12, and ever since then I’ve been knowing less and less.

Of course there are the less typical teenagers who don’t express the same unaware overconfidence. They can be extremely competent at a particular thing (let’s call it a domain), like writing to take a purely random example, yet are extremely unconfident of their ability.

Well Kruger and Dunning (1999) have an explanation for that too. Competent people tend to think everyone else is competent too, so they tend too underestimate their ability relative to everyone else.

Teachers can easily fall into a similar trap, because we will often, quite unintentionally and unconsciously, assume students know more than they do. This is one of the reasons peer-teaching works so well. Students are more likely to know where their peers are coming from, and what they know to begin with.

The NY Times’ Errol Morris has a great interview with one of this study’s authors.

I’ll end with the most wonderful concluding remarks, which really put this whole study in perspective:

In sum, we present this article as an exploration into why people tend to hold overly optimistic and miscalibrated views about themselves. We propose that those with limited knowledge in a domain suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach mistaken conclusions and make regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it. Although we feel we have done a competent job in making a strong case for this analysis, studying it empirically, and drawing out relevant implications, our thesis leaves us with one haunting worry that we cannot vanquish. That worry is that this article may contain faulty logic, method- ological errors, or poor communication. Let us assure our readers that to the extent this article is imperfect, it is not a sin we have committed knowingly.

—Kruger and Dunning (1999)

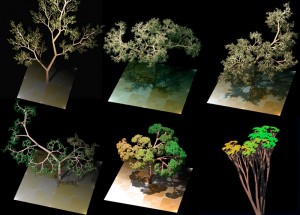

Boredom in a fractal world

A few of my students have been complaining that we don’t do enough different things from week to week for them to write a different newsletter article every Friday. PE, after all, is still PE, especially if we’re playing the same game this week as we did during the last.

So I’ve been thinking of ways to disabuse them of the notion that anything can be boring or uninteresting in this wonderful, remarkable world. A world of fractal symmetry, where a variegated leaf, a deciduous tree and a continental river system all look the same from slightly different points of view. A counterintuitive world where the smallest change, a handshake at the end of a game, or a butterfly flapping its wings can fundamentally change the nature of the simplest and the most complex systems.

“Chaos is found in greatest abundance wherever order is being sought. It always defeats order, because it is better organized.”

— Terry Pratchett (Interesting Times)

There are two things I want to try, and I may do them in tandem. The first is to give special writing assignments where students have to describe a set of increasingly simple objects, with increasingly longer minimum word limits. I have not had to impose minimum word limits for writing assignments because peer sharing and peer review have established good standards on their own. Describing a tree, a coin, a 2×4, a racquetball in a few hundred words would be an exercise in observation and figurative language.

To do good writing and observation it often helps to have good mentor texts. We’re doing poetry this cycle and students are presenting their poems to the class during our morning community meetings. It had been my intention to make this an ongoing thing, so I think I’ll continue it, but for the next phase of presentations, have them chose descriptive poems like Wordsworth’s “Yew Trees“*.

The world is too interesting a place to let boredom get between you and it.

Leadership and competitive games

“Treat a person as he is, and he will remain as he is. Treat him as he could be, and he will become what he should be.”

–Jimmy Johnson

As much as I want to offer my students near-autonomy for at least a small part of the day, I am finding it necessary to reinforce the lessons of the classroom during PE. Physical education is an important part of a holistic education not just for the fact that healthy bodies lead to healthy minds, but because it offers another domain for students to develop their leadership skills.

I’ve found that not everyone who is great in the classroom will be great on the playing field, so students who are often learning from their peers when they’re inside, get a chance to teach and lead others. Often however, because they are unused to it, they need a little guidance to recognize the reversal of roles.

It is also interesting to note that some students who are great at peer-teaching the academics can get really riled up on the field and loose all sense of perspective, forgetting those carefully taught collaboration skills. This is particularly true when we play competitive games and they have to balance competition and collaboration. Fortunately, there is a well established term (even if not gender neutral) that sums up appropriate behavior in competition, sportsmanship.