The first video is a quick overview of why Mendeleev’s table of elements was found to be so useful.

The second video goes into more depth about the periods and the groups.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

The first video is a quick overview of why Mendeleev’s table of elements was found to be so useful.

The second video goes into more depth about the periods and the groups.

Are the elements of larger atoms harder to melt than those of smaller atoms?

We can investigate this type of question if we assume that bigger atoms have more protons (larger atomic number), and compare the atomic number to the properties of the elements.

Data: Properties of the First 20 Elements

Your job is to use the data linked above to draw a graph to show the relationship between Atomic Number of the element and the property you are assigned.

What is the relationship between the number of valence electrons of the elements in the data table and the property you were assigned.

Bonus 1: The atomic number can be used as a proxy for the size of the element because it gives the number of protons, but it’s not a perfect proxy. What is the relationship between the atomic number and the atomic mass of the elements?

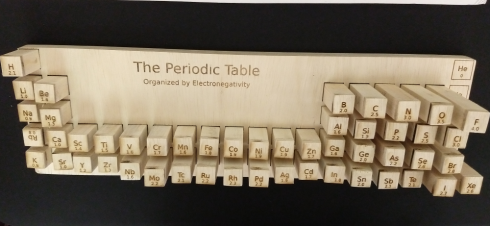

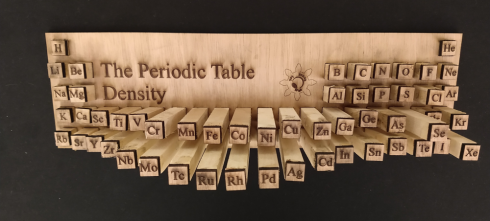

Ms. Fu’s chemistry class were given a project to make 3d periodic tables based on the properties of the elements. A few groups went with Makerspace options, using the new vinyl cutter and laser.

The part that took the longest was marking all the columns for cutting. A worthwhile assignment would be to write a program to automatically make the cut-marks in an svg file that can be etched with the laser.

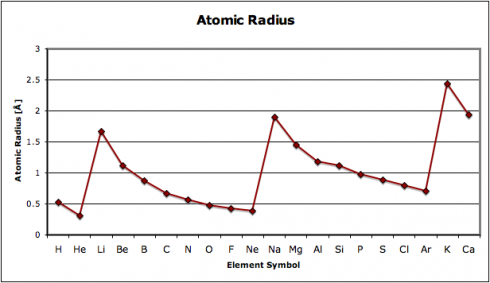

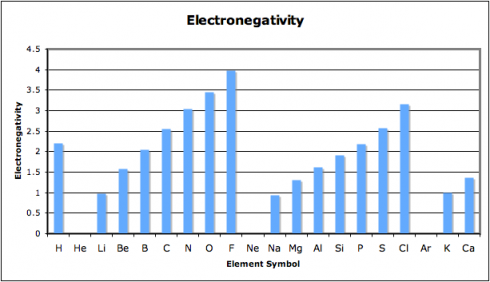

Why is the periodic table called the periodic table? Because of the periodic changes in the properties of the elements: there are patterns to the properties that repeat, time after time, as you go through the sequence of the elements. One key repetition, which affects the way different elements react, is in the electron configurations, however, other properties change as well. In fact, history of the periodic table

is a story of scientists trying to figure out the properties of unknown elements (not to mention figuring out that there were undiscovered elements) based on what they knew about the periodicity of the known elements.

File: periodic-table-properties.xls

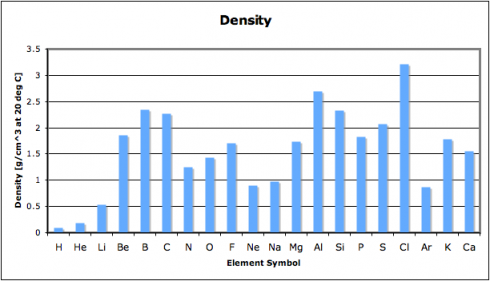

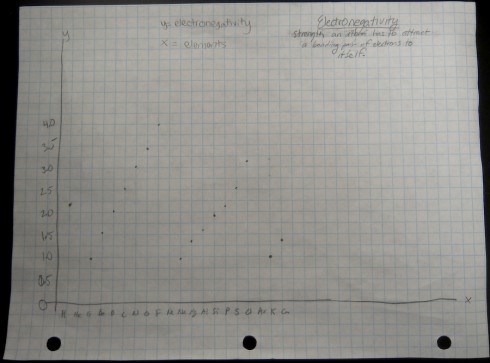

In this exercise, we look at four different properties that students need to be aware of: density, melting point, ionization energy, and electronegativity. I’ve compiled the data in this spreadsheet: periodic-table-properties.xls; and I handed out the first page, with the properties of the first 38 elements (periodic-table-properties.xls.pdf).

I broke the class into pairs and had each pair graph one of the four sets of data. With 16 students that meant that we had a replicate of each graph, so I could use the redundancy as a quick check that they’d done them correctly.

As they put drew their graphs I went around the classroom, paying special attention to the students working on ionization energy and electronegativity. Especially for the latter, I’d picked pairs who I figured would be able to get the graphs done quickly but would appreciate the extra challenge of figuring out what electronegativity actually is. This way, when everyone was done, the students could use their graphs to look for the patterns and explain what they’d found to the rest of the class.

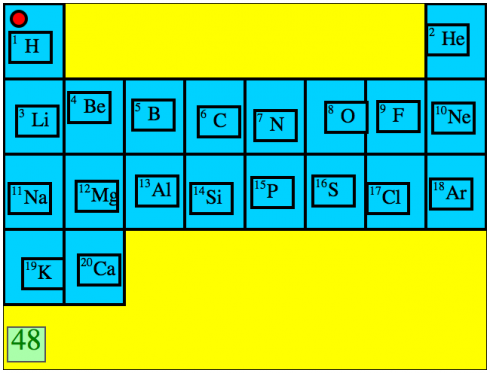

My middle school class is about to cover some very basic chemistry so I’ve asked them to memorize the first 20 elements in their correct order on the periodic table. To help, I’ve put together this interactive exercise where they drag an icon of the element to its correct place on the table. It says the name of the element whenever you start dragging a tile with the symbol. It’s also timed so students can quantify and compare how good they are.

In this first prototype the elements are presented in order, but I figure that additional levels could have:

This was put together using HTML5 and Javascript. KineticJS was particularly useful. It should, in theory, work in any browser (but I have only tested it in Firefox and Google Chrome) and on touch-screen tablets as well.

I have a neat little tea strainer that sits inside my almost perfect teacup, yet I’m usually at a loss about what to do with it when I take it out of the cup. When the lid is upside down, the strainer can sit nicely into a circular inset that seem perfectly designed for it; however, if I want to use the lid to keep my tea warm — as I am wont to do — I have to move the strainer somewhere else.

One option is to just put the strainer in another cup, but then air can’t circulate around it, and instead of drying, the used tea leaves stay wet and, eventually, turn moldy. A flat saucer would be better, but not perfect.

Of course, I could just empty out the strainer, wash and dry it as soon as I’m done steeping the leaves, but there are a few ancillary considerations with respect to time that make this a sub-optimal solution.

So, since we have a kiln on campus that sees regular use, I thought I’d sit in on the Middle School art class and make my own ceramic tea strainer holder. Since I’ve also been thinking about Philip Stewart’s spiral, and de Chancourtois‘ helictical periodic tables, and been inspired by Bert Geyer’s attempts at making sonnets tangible, it eventually occurred to me that an open helictical form would work fairly well for my purposes.

I’ve cobbled together a design using Inkscape, and layered it onto a cylinder in Sketchup to see what it would look like.

So far the reactions from students has been quite diverse. I have one volunteer who’s wants to help, and I’ve sparked some discussion as to if what I’m doing actually qualifies as art. There is a lot of curiosity though. The middle-schoolers will probably be doing some type of physical representation of the periodic table, so I’m hoping this project gets them to think more broadly about what they might be able to do.

Spurred by Philip Stewart‘s comment that, “The first ever image of the periodic system was a helix, wound round a cylinder by a Frenchman, Chancourtois, in 1862,” I was looking up de Chancourtois and came across David Black’s Periodic Table Videos. They put things into a useful historical context as they explore how the patterns of periodicity were discovered, in fits and starts, until Mendeleev came up with his version, which is pretty much the basis of the one we know today.

The cylindrical version is pretty neat. I think I’ll suggest it as a possible small project if any of my students is looking for one. You can, however, find another interesting 3d periodic table (the Alexander Arrangement) online.