I try not to post things with anything approaching obscene language, but sometimes, as in this piece, called “Storm” by Tim Minchin, it’s a small part in the service of a much bigger, more significant idea. Anyway, this one might not be for the kids.

Tag: philosophy

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

I get this question occasionally from my students, and the answer is, of course, that it depends on how you define the word “sound”. Jim Baggott, on the Oxford University Press blog, goes into more detail about the roots of this philosophical conundrum, and makes the parallel to quantum physics.

Physics and philosophy are a dangerous pairing, particularly since if you know enough about one to speak intelligently about it, your probably way out of your depth in talking about the other. Just because you’re an expert in one field does not mean you’re going to be an expert in another. This is especially true of physics and philosophy, which approach the world from such different perspectives and use such different languages: to a physicist, “sound” refers to the vibrations in the air, while a philosopher might argue that “sound” only exists in our minds.

Philosophers have long argued that sound, colour, taste, smell and touch are all secondary qualities which exist only in our minds. We have no basis for our common-sense assumption that these secondary qualities reflect or represent reality as it really is. So, if we interpret the word ‘sound’ to mean a human experience rather than a physical phenomenon, then when there is nobody around there is a sense in which the falling tree makes no sound at all.

— Jim Baggott: Quantum Theory: If a tree falls in forest…

Montessori, cooperation and the Tragedy of the Commons

The essence of dramatic tragedy is not unhappiness. It resides in the solemnity of the remorseless working of things.

— Whitehead (1948) via Hardin (1968)

One of the greatest challenges in designing a cooperative environment is dealing with the potential for free-riding and abuse of shared resources. When dinner needs to be made but one member of the group will not participate everyone suffers, even those who contribute fully. Often, someone else or the rest of the group will step up and do the job of the free-rider, who has then achieved their objective. But what is the appropriate consequence? The social opprobrium of their peers is enough for some, others though seem unfazed.

Overuse of resources is a similar problem, which economists refer to as the tragedy of the commons (Hardin, 1968). When the extra-large bag of M&M’s is full, everyone can grab as many as they desire and everyone is happy. When resources are scarce, however, everyone grabbing is a recipe for disaster. Scarce resources need to be rationed in a way that everyone views as fair. Yet the rational behavior of the individual is to try to maximize their utility by taking as many as they need, regardless of the desires of everyone else, and especially if they’re first in line and no-one else is counting.

Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all. … The individual benefits as an individual from his ability to deny the truth even though society as a whole, of which he is a part, suffers.

— Hardin (1968)

The market solution to the commons problems is to make them not commons. This is usually done by assigning property rights to the previously common resource and allowing the owners to trade. This puts a price on what was once a “free” resource. Of course the price was always there; someone or someones had to go without when the M&M’s ran out (resource depletion). Unfortunately this is particularly difficult when you dealing with a non-currency economy, though I’m sure it could be done.

Reading through Hardin’s original Tragedy of the Commons article it seem that if the embarrassment of violating social norms is insufficient incentive for temperance then some sort of mutually agreed form of coercion is necessary. Interestingly, Hardin was arguing for population control, but the point still stands.

We’re due to have the small groups discuss how the worked together over the last cycle so we’ll see how that goes, but I think we’ll have to discuss the issue of the commons as a whole group when we next have our discussion of classroom issues. I’d like to raise the point that what happens in the classroom is a microcosm of larger society and get in a little environmental economics at the same time.

Education can counteract the natural tendency to do the wrong thing, but the inexorable succession of generations requires that the basis for this knowledge be constantly refreshed.

— Hardin (1968)

It all depends on your point of view

Over the winter, we read Brian Swimme’s The Hidden Heart of the Cosmos as part of the HMC Montessori Training Program. Swimme is one of those people trying to reconcile science and religion, or at least some type of spirituality.

He argues that crass commercialism, embodied by the consumer culture and a lot of television that is excrescent and dis-empowering, has replaced the spirituality that our ancestors sought in the dark, quiet reaches of the night. Then they had the time to contemplate the meaning of life and their place and even purpose in the universe. Now we try to respond to a rapidly changing world with no time to consider the fundamental questions.

I tend to be a bit skeptical about just how useful it is to examine the intersection of the sacred and the scientific. The scientific perspective is a powerful way of looking at the world. Spirituality seems to be one of those fundamental needs of human beings. I’ve never found it difficult to see the wonder in the natural world around me (which is why things like texture photography fascinate me). But when we try to describe the natural world in terms of religion and spirituality, I get a bit uncomfortable. When you’re treading the boundary between what we can observe objectively and what we feel subjectively, it’s all to easy to slip between one and the other. To stretch the scientific truth to accommodate the poetic language or metaphor. And so, it’s the little things that end up bugging me to no end.

Copernicus revolutionized the way western civilization viewed the world and itself, Swimme notes. The Earth was no longer at the center of the universe. The Sun did not revolve around us, we revolved around it. So when you see the Sun going down at sunset, it’s not really going down, the Earth is turning away. Except that it is and it isn’t. If the Earth is rotating you away from the Sun, or if the Sun in going down past the horizon, is just a matter of your point of view.

If you want to describe the motion of the planets, the easiest model to construct is one where the Sun is the stationary reference point at the center of the solar system. But, if you were a glutton for punishment, you could write the equations of motion such that the you were the stationary reference point and everything else moved relative to you. It’s a bit like thinking about yourself on a boat floating down a stream. To an observer sitting on the bank you are moving downstream, but to you, the guy on the bank is moving and you’re staying in the same place.

So I get a little agitated when Swimme points out how remarkable it is to think about the fact that we occupy such a small place in such a large universe. He argues that it should broaden your perspective on the universe, and open your mind to larger questions. But I find it just as remarkable, or perhaps even a little more so, to consider the world where I am not moving, and everything else is spinning in some ridiculously complicated dance around me.

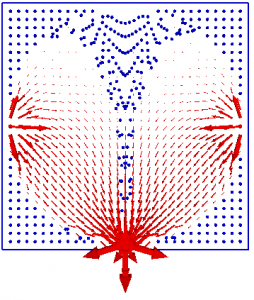

I think of Swimme at times when I’m trying to model solute transport through a fluid. Should I try to follow the motion of individual particles with the fluid. Should I take the broader view of the flow through the system. Or should I try to mix the two approaches. Either way, the math should give the same result, since I’m just trying to describe the same thing from different point of view (of course the problem is in how compatible the different approaches are to being programmed).

I know I’m missing the main point of the Hidden Heart of the Cosmos here because of my own hang-ups, so I’ll post an excellent video interview of Brian Swimme by Bob Wright, the author of Nonzero, so he can better explain himself. (If you can’t get the video to play, you can read the transcript.)

Approximating reality

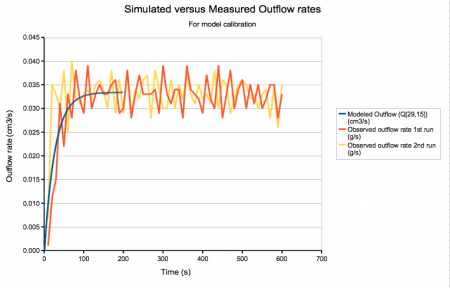

The world is ridiculously complicated. We construct models to represent what we see and think we understand. Simple models of complex phenomena, and we’re happy when our models represent the most important patterns.

We would, of course, often like to understand the details, so we add more detail to our models. And our models get closer to reality. Yet as our models represent the world in more and more detail they themselves become more and more complex. All the simple parts of the models start to interact in increasingly unexpected ways, until it becomes almost as difficult to interpret the model as it is to understand the real world.

It’s a good thing we see beauty in complexity.

What is life and what is human?

Life has four needs, six characteristics and sixteen patterns, but things only get really interesting with viruses that straddle the line between life and non-life. You can run into similar problems when you ask the question of what makes us human.

Both these questions come up in stories like Pinocchio, and any number of robot books, such as John Sladek’s Roderick. Probably because good books go a lot farther in describing characters rather than appearances, you often start with the question, are they sentient and then backtrack to the question of if they’re alive or not.

Interestingly, many of my students equate the question, are they sentient, with the query, are they human? (A fascinating result given the propensity of humanity to divide into groups based on looks.) Which gives rise to the interesting conundrum, can something/someone be “human” and still not alive? We’ve had some fascinating discussions around that question too.

A great place to encounter these issues is in Mary Shelly’s novel Frankenstein, which also nicely ties-in with the science curriculum since you will probably find it useful to draw out the Frankenstein family tree to keep track of the story. In addition, the historical setting of the book relates to social world issues as the book describes life in the early 19th century, and you realize that the issue of our relationship with technology and science was coming up 200 years ago.

A lighter variant on Frankenstein is Terry Pratchett’s Feet of Clay. It’s a story about golums who are powered only by the words in their head. Unlike Asimov’s three rules of robotics the words are not literal instructions like the programmer’s code, they can be much more metaphorical, like a receipt. Yet, in the end, many of the same questions about life and humanity arise.