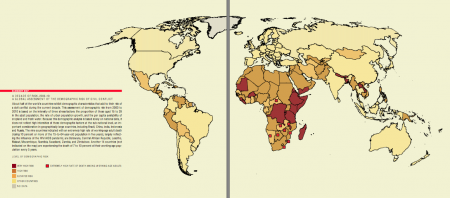

For much of the U.S., last winter was pretty cold. If you look at the maps above, you can see that the eastern United States was up to 4 °C colder than normal in December. However, if you look a little further north into Canada, you’ll see a broad, pink region, where the temperatures were up to 11 °C warmer than normal.

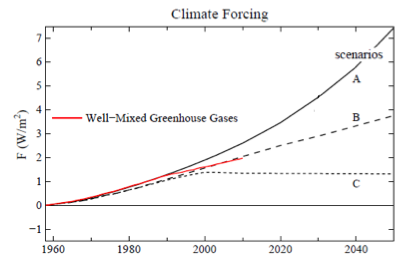

The rate at which the world has been warming has been accelerating. It’s been interesting watching the predictions of the relatively crude computer models of the 1980’s coming true.

Although, it’s really the broadest, more general predictions that tend to be more reliable. One of those predictions, that’s been consistent for a long time and with a lot of different models, is that the poles would warm significantly faster than the rest of the planet.

What’s also been interesting, if somewhat depressing, is seeing the political consensus lag behind the scientific consensus. Twenty years ago there was a real debate in the scientific community about if global temperatures were rising. Now scientists argue mainly about what to do: reduce greenhouse gas pollution, adapt to the inevitable, or some mix of the two. Yet two weeks ago the House Science Committee heard testimony from a professor of marketing, advocating for an end to all government funding of climate research. Perhaps the belief is that if we don’t look it won’t happen.

Curiously, even research teams funded by people who politically oppose global warming, are just confirming the results of all the other scientific groups. Unsurprisingly, they’re now getting heat from their former supporters.

At the same time, Kate (on climatesafety.org) observes that NASA’s James Hansen has had to add a new color (pink on the graphs at the top of the page) to his climate anomaly maps because of the unexpectedly large warming over last winter.