The following are my notes for the exercise that resulted in the Oil Traps and Deltas in the Sandbox post.

Trapping Oil

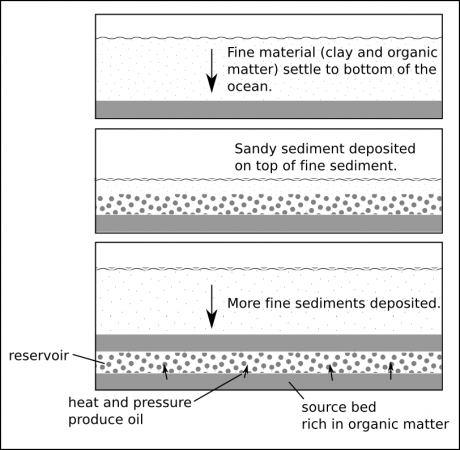

Crude oil is extracted from layers of sand that can be deep beneath the land surface, but it was not created there. Oil comes from organic material, dead plants and animals, that sink to the bottom of the ocean or large lakes. Since organic material is not very dense, it only reaches the bottom of ocean in calm places where there are not a lot of currents or waves that can mix it back into the water. In these calm places, other very small particles like clay can also settle down.

Over time, millions of years, this material gets buried beneath other sediments, compressing it and heating it up. Together the organic material and the clay form a type of sedimentary rock called shale. As the shale gets buried deeper and deeper and it gets hotter and hotter, and the organic matter gets cooked which causes it to release the chemical we know as natural gas (methane) and the mixture of organic chemicals we call crude oil (see the formation of oil and natural gas).

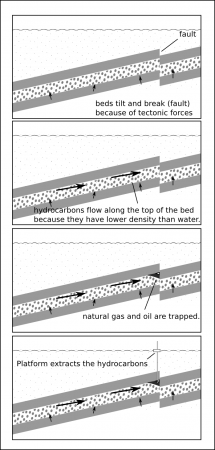

Shale beds tend to be pretty tightly packed, and they slowly release the oil and natural gas into the layers of sediment around them. If these layers are made of sandstone, where there is much more space for fluids to move between the grains of sand, the hydrocarbons will flow along the beds until they are trapped (Figure 2).

In this exercise, we will use the wave tank to simulate the formation of the geologic layers that produce oil.

Materials

- Wave tank

- Play sand (10x 20kg bags)

- Colored sand (2 bags)

Observations

For your observations, you will sketch what happens to the delta in the tank every time something significant changes.

Procedure

- Fill the upper half of the tank with sand leaving the lower half empty.

- Fill the empty part with water until it starts to overflow at the lower outlet.

- Move the hose to the higher end so that it creates a stream and washes sand down to the bottom end — observe the formation of the delta.

- Observe how the delta builds out (progrades) into the water.

- After about 10 minutes dump the colored sand into the stream and let it be transported onto the delta.

- After most of the colored sand has been transported, raise the outlet so that the water level in the tank rises to the higher level. — Note how the delta forms at a new place.

- After about 10 more minutes dump another set of colored sand and allow it to be deposited on the delta.

- Now lower the outlet to the original, low level and observe what happens.

- After about 10 minutes, turn off the hose and drain all of the water from the tank.

- When the tank is dry, use the shovel to excavate a trench down the middle of the sand tank to expose the cross-section of the delta.

Analysis

1. How did changing the water level affect the formation of the delta.

- - - - - -

2. When you excavated the trench, did you observe the layers of different colored sand in the delta? Draw a diagram showing what you observed. Describe what you observed here.

- - - - - -

3. Was this a realistic simulation of the way oil reservoirs are formed. Please describe all of the things you think are accurate, and all of the things you think are not realistic?

- - - - - -