We’ve acquired a selection of manures and composts for revitalizing our orchard, but don’t quite know if they’re safe to add to the soil. Too much nitrogen in the manure will “burn” plants. Therefore, we tried a simple pH test as a quick-and-dirty proxy for estimating the nitrogen/ammonia concentration of the samples.

Since we’ve been working on the orchard, Dr. Sansone has contributed a pile of composted horse manure, a pile of composted kitchen scraps, and a pile of mixed compost and pigeon manure. You’re supposed to let bird manure compost for quite a while (months to years) before using it because of the high ammonia content that is produced by all the uric acid produced by birds.

The “burning” of the plants happens, primarily, when there’s too much ammonia in the manure. Ammonia becomes basic (alkaline) when dissolved in water (thanks to Dillon for looking that up for us). The ammonia (NH3) snags a hydrogen from a water molecule (H2O) making ammonium (NH4+) and hydroxide ions (OH–).

NH3 + H2O <==> NH4+ + OH–

The loose hydroxides make the water basic.

The ammonia, in this case, comes primarily from the breakdown of urea and uric acid in the manure. Animals produce urea (in the liver) from ammonia in the body. The ammonia in the body comes from the breakdown of excess amino acids in food. We get the amino acids from digestion of proteins (proteins are long chains of amino acids. The urea is excreted in urine, or in the case of birds as uric acid mixed in with their feces.

Experimental Procedure

- Weigh 100 g of soil/compost/manure.

- Add enough water to fill the beaker to the 300 ml level. Some of the samples absorbed significant amounts of water necessitating more water to get to the 300 ml level.

- Stir to thoroughly mix (and melt any ice in the soil) then let sit for 5 minutes.

- Pour mixture through filter (we used coffee filters).

- Test the pH of the filtrate (the liquid that’s passed through the filter) using pH test strips.

Important Note: We did the experiment under the hood, because the pigeon manure was quite pungent.

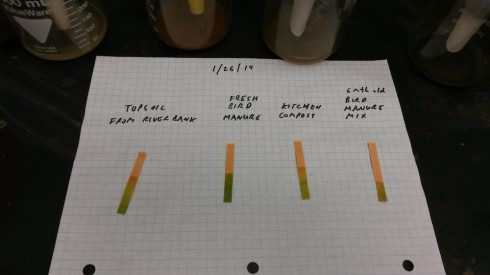

In addition to testing the manure and compost, we tried a soil sample from the creek bank, and a sample of fresh pigeon manure to serve as controls.

Results

The results were close to what we expected (see Table 1), with the bird manure having the highest pH.

Table 1: pH of soil, manure, and compost samples.

| Sample | pH |

|---|---|

| Topsoil from Creek Bank | 6 |

| Fresh Pigeon Manure | 8-9 |

| Kitchen Compost | 5-6 |

| 6 Month Old Pigeon Manure/Compost Mix | 6-7 |

Discussion/Conclusion

While the high pH of the fresh pigeon manure suggests that it probably too “hot” to directly apply, it was good to see that the composted manure had a pH much closer to neutral.

This is a simple way to test the soil, so it may be useful for students to do this as we get new types of fertilizer.