Mike Schmidt passed along this link to Lisa Winter’s post collecting 21 GIFs That Explain Mathematical Concepts.

For example:

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

Mike Schmidt passed along this link to Lisa Winter’s post collecting 21 GIFs That Explain Mathematical Concepts.

For example:

On the recommendation of Mr. Schmidt, two of my students have been quite fascinated over the last few days trying to solve problems on Project Euler. They’ve been working on them together to, I suspect, the detriment of some of their other classes, but as their math teacher I find it hard to object.

An example problem is something like this:

If we list all the natural numbers below 10 that are multiples of 3 or 5, we get 3, 5, 6 and 9. The sum of these multiples is 23.

Find the sum of all the multiples of 3 or 5 below 1000.

They’ve been solving them numerically using Python. It’s been quite fascinating to see.

I’ve slapped together this simple VPython program to introduce sinusoidal functions to my pre-Calculus students.

The specific functions shown on the graph are based on the general function:

![]()

where:

When I first introduce sinusoidal functions to my pre-Calculus students I have them make tables of the functions (from -2π to 2π with an interval of π/8) and then plot the functions. Then I’ll have them draw sets of sine functions so they can observe different frequencies, amplitudes, and phases.

from visual import *

class sin_func:

def __init__(self, x, amp=1., freq=1., phase=0.0):

self.x = x

self.amp = amp

self.freq = freq

self.phase = phase

self.curve = curve(color=color.red, x=self.x, y=self.f(x), radius=0.05)

self.label = label(pos=(xmin/2.0,ymin), text="Hi",box=False, height=30)

def f(self, x):

y = self.amp * sin(self.freq*x+self.phase)

return y

def update(self, amp, freq, phase):

self.amp = amp

self.freq = freq

self.phase = phase

self.curve.y = self.f(x)

self.label.text = self.get_eqn()

def get_eqn(self):

if self.phase == 0.0:

tphase = ""

elif (self.phase > 0):

tphase = u" + %i\u03C0/8" % int(self.phase*8.0/pi)

else:

tphase = u" - %i\u03C0/8" % int(abs(self.phase*8.0/pi))

print self.phase*8.0/pi

txt = "y = %ssin(%sx %s)" % (simplify_num(self.amp), simplify_num(self.freq), tphase)

return txt

def simplify_num(num):

if (num == 1):

snum = ""

elif (num == -1):

snum = "-"

else:

snum = str(num).split(".")[0]+" "

return snum

amp = 1.0

freq = 1.0

damp = 1.0

dfreq = 1.0

phase = 0.0

dphase = pi/8.0

xmin = -2*pi

xmax = 2*pi

dx = 0.1

ymin = -3

ymax = 3

scene.width=640

scene.height=480

xaxis = curve(pos=[(xmin,0),(xmax,0)])

yaxis = curve(pos=[(0,ymin),(0,ymax)])

x = arange(xmin, xmax, dx)

#y = f(x)

func = sin_func(x=x)

func.update(amp, freq, phase)

while 1: #theta <= 2*pi:

rate(60)

if scene.kb.keys: # is there an event waiting to be processed?

s = scene.kb.getkey() # obtain keyboard information

#print s

if s == "up":

amp += damp

if s == "down":

amp -= damp

if s == "right":

freq += dfreq

if s == "left":

freq -= dfreq

if s == "s":

phase += dphase

if s == "a":

phase -= dphase

func.update(amp, freq, phase)

#update_curve(func, y)

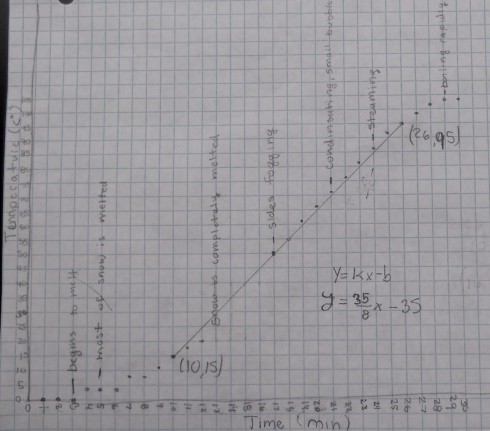

This is my quick, and expanding, reference for easy-to-do experiments for students studying different types of functions.

Linear equations: y = mx + b

Quadratic equations: y = ax2 + bx + c

Exponential functions: y = aekx

Square Root Functions: y = ax1/2

Trigonometric Functions: y = asin(bx)+c

One of the jobs my class helped with at the Heifer Ranch was planting garlic in the Heifer CSA garden. The gardeners had laid rows and rows of this black plastic mulch to keep down the weeds, protect the soil, and help keep the ground warm over the winter.

We then used an improvised puncher to put holes in the plastic through which we could plant cloves of garlic pointy side up. The puncher was a simple flat piece of plywood, about one foot by three feet in dimensions, with a set of bolts drilled through. The bolts extended a few inches below the board and would be pressed through the black plastic. Two handles on each side of the board made it easier for two people to maneuver and punch row after row of holes.

As I took my turn punching holes, we did the math to figure out just how much garlic we were planting. A quick count of the last imprint of the puncher showed about 15 holes per punch. Each row was about 200 feet long, which made for approximately 3,000 heads of garlic per row.

We managed to plant one and a half rows. That meant about 4,500 garlic cloves. With ten people planting, that meant each person planted about 450 cloves. Not bad for an afternoon’s work.

Here’s another attempt to create embeddable graphs of mathematical functions. This one allows users to enter the equation in text form, has the option to enter the domain of the function, and expects there to be multiple functions plotted at the same time. Instead of writing the plotting functions myself I used the FLOT plotting library.

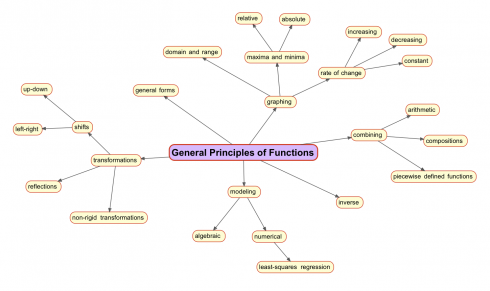

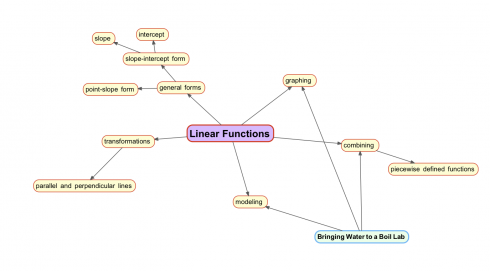

This year I’m trying teaching pre-Calculus (and it should work for some parts of algebra as well) based on this concept map to use as a general way of looking at functions. Each different type of function can by analyzed by adapting the map. So linear functions should look like this:

You’ll note the bringing water to a boil lab at the bottom left. It’s an adaptation of the melting snow lab my middle schoolers did. For the study of linear equations we’ll define the function using piecewise defined functions.

My middle school class stumbled upon a nice probability problem that I might just use in my pre-calculus exam.

You see, four of my students took cuttings of oregano plants from the pre-school herb gardens when we were studying asexual reproduction, but only three of them grew roots.

That gives a 75% success rate.

![]()

The next time I do it, however, I want each student to have some success. If I have them take two cuttings that should increase the chances that at least plant will grow. And we can quantify this.

If the probability of success for each cutting is 75% then the probability of failure is 25%.

P[failure] = 0.25

Given a probability of one plant failing of 25%, the probability of both plants failing is the probability of one plant failing and the other plant failing, which, mathematically, is:

P[2 failures] = P[failure] x P[failure]

P[2 failures] = 0.25 x 0.25

P[2 failures] = 0.252

P[2 failures] = 0.0625

So the probability of at least one plant growing is the opposite of the probability of two failures:

P[at least 1 success of two plants] = 1 – P[2 failures]

P[at least 1 success of two plants] = 1 – 0.0625

P[at least 1 success of two plants] = 0.9375

which is about 94%.

If I had the students plant three cuttings instead, then the probability of at least one success would be:

P[at least 1 success of 3 plants] = 1 – P[3 failures]

P[at least 1 success of 3 plants] = 1 – 0.253

P[at least 1 success of 3 plants] = 1 – 0.02

P[at least 1 success of 3 plants] = 0.98

So 98%.

This means that if I had a class of 100 students then I would expect only two students to not have any cuttings grow roots.

In fact, from the work I’ve done here, I can write an equation linking the number of cuttings (let’s call this n) and the probability of success (P). I did this with my pre-calculus class today:

![]()

so if each student tries 4 cuttings, the probability of success is:

P = 1 – 0.254

P = 1 – 0.004

P = 0.996

Which is 96.6%, which would make me pretty confident that at least one will grow roots.

However, what if I knew the probability of success I needed and then wanted to back calculate the number of plants I’d need to achieve that probability, I could rewrite the equation solving for n:

Start with:

![]()

isolate the term with n by moving it to the other side of the equation, and switching P as well:

![]()

take the natural log of both sides (we could take the log to the base 10 if we wanted, or any other base log, but ln should work just as well).

![]()

now use the rules of logarithms to bring the exponent down into a multiplication:

![]()

solving for n gives:

![]()

Note that the probability has to be given as a fraction (between 0 and 1), so 90% is P = 0.9. A few of my students made that mistake.

At the same time my students were making oregano cuttings, six of them were making cuttings of lavender. Only one of the cuttings grew.

So now I need to find out how many lavender cuttings each student will have to make for me to be 90% sure that at least one of their cuttings will grow roots.

Students can do the math (either by doing the calculations for each step, or by writing and solving the exponential equation you can deduce from the description above), but the graph below shows the results: